When Louis XV appointed Madeleine Françoise Basseporte the resident botanical artist at his Jardin du Roi, he was making history. No women before, or even since, had been the designated dessinateur au roi. But this was the era of the Enlightenment, where new ideas were flourishing and scientific methods were overcoming tradition. For over 50 years, until she supposedly died with a paintbrush in her hand, Mademoiselle Basseporte observed, dissected, sketched and illustrated exquisitely detailed flowers and plants, often adding her own personal touch to her botanical art.

She was born on the Île Saint-Louis on 28 April 1701, the daughter of a wine merchant. Unfortunately her father’s business failed and then he died, so she had to find a way to support herself and her mother. Thankfully she showed artistic talent at an early age and opened an art school for girls in the Marais district in Paris, as well as taking on commissions for portraits. Unfortunately, only one of her portrait paintings survive today, that of a young woman, now hanging in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam.

How and why Madeleine decided she was going to paint botanical art at the Jardin du Roi is not known. All we do know is that in 1726 she was taking lessons with the chief dessinateur and within ten years she had been named as his successor. But for those ten years she had not been paid and the chief, Claude Aubriet, had often signed his name to her work and taken the credit (and the money). Years later, when Aubriet died she briefly thought about seeking recompense from his estate, arguing that his heirs would profit from her own art, but withdrew her complaint. She may have felt pressured to do so, or was choosing to keep the peace. As the only woman actually employed at the Jardin, and one with such high visibility, one can only imagine the extra burden she faced.

There was a vast difference between being a flower painter and creating botanical art. Whilst Madeleine may have supplemented her (meagre) income with flower paintings for rich customers and decorating objets de luxe such as porcelaine and textiles, her talent lay in her exquisite illustrations of plants in the Jardin du Roi. And to create intricate and precise reproductions, the artist became a botanist. A flower newly in blossom, or an exotic species from across the seas had to be recorded for prosperity, for immortality, so it must be examined inside and out, delicately opened to reveal the ovary, the stigma, the stamen, and then ponder over how to best portray the myriad of shades in its gossamer petals. Madeleine’s works were “admired by artists and botanists alike”.

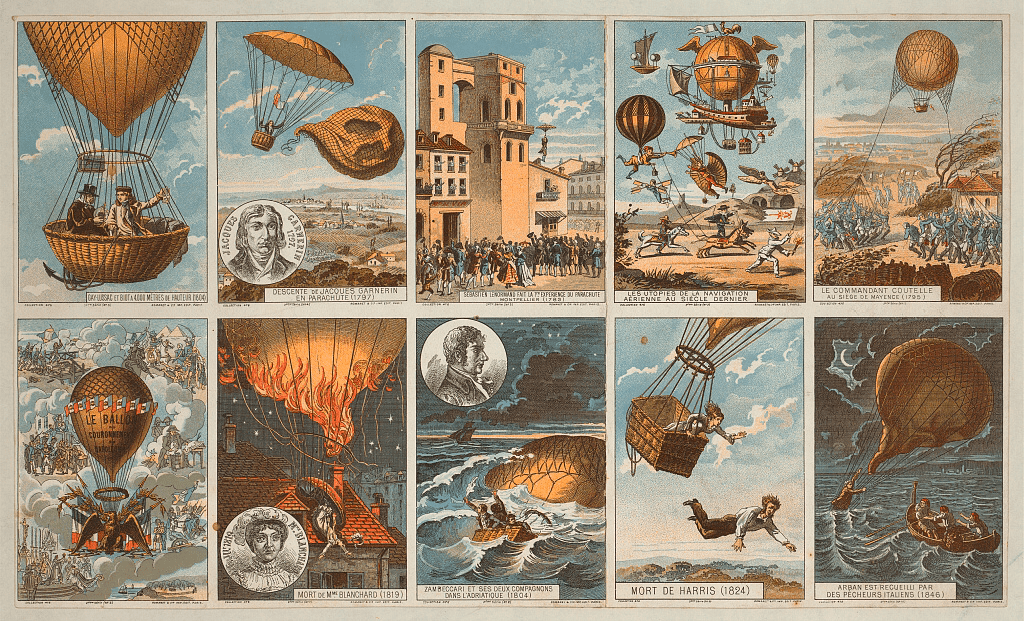

The plant world was in a state of flux in eighteeenth century Europe, the age of the Enlightenment, with new discoveries in natural history as ships sailed to all four corners of the globe seeking peregrine species of plants. In the light of these discoveries the Jardin du Roi transformed from a garden devoted to medicine to one designed around the new and exotic flowers and plants being introduced from the New World. Mlle Basseporte was seen often in the garden or in the newly built hothouses with her wheelbarrow porting her easel, chalks, paints and brushes.

Aside from painting, giving lessons in botanical art and illustration was a large part of her role (she also taught art to poor girls at her own expense). The Jardin du Roi was fairly unusual for its time in that lessons in botany and natural history were given to men and women alike, and many artists who later became well known learnt the skill of drawing flowers from Mlle Basseporte. Even the daughters of Louis XV were supposedly taught flower illustration, a very suitable occupation for young women. It is not clear which daughters were taught (there were eight in total); if it were the five youngest then Madeleine would have had to travel to the Royal Abbey of Fontevraud as they were educated here for much of their childhood.

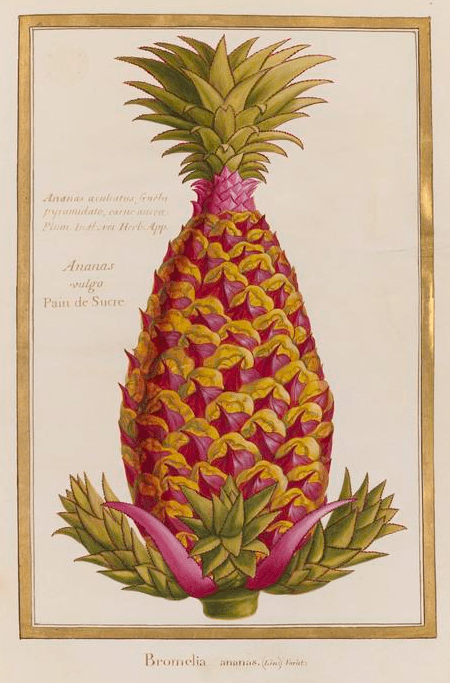

As the official dessinateur au roi she was in service to the king and his retinue, being obliged to produce twelve vélins or plants painted on vellum each year. In 1774 she rushed to Versailles at the request of the Comte de Maurepas to paint birds and monkeys, part of a gift given to the king, and several years later was urged to hurry to the Château de Compiègne so that a fresh fruit from the Indies could be preserved on vellum before it perished:

“The king orders me, Mademoiselle, to inform you on his behalf that he wishes that as soon as my letter is received, you go to Compiègne with all that is necessary for you to paint a singular fruit from the Indies, which has just been given to his majesty and which still has all its freshness. It is a species of pineapple, which has a crown of extraordinary form, and several other alterations which are not commonly found in these kinds of fruit”.

Letter from Monsieur le comte d’Argenson

The garden world was aflutter in 1765 when a Chilean strawberry plant in the garden of the Trianon produced four berries, a highly unusual and much sought after occurrence, and the services of Mlle Basseporte in capturing the strawberries on their stalk were required before the plant could be presented to the king. Madame de Pompadour, mistress to Louis XV, often sought elegant paintings of flowers from her gardens at Bellevue (a royal château which no longer exists).

By all accounts Madeleine Basseporte was not only beautiful, but a wonderfully caring individual, though if she had not shown such “womanly” features it is unlikely she would have succeeded in her field at this time. Carl Linnaeus, a Swedish botanist famous for his taxonomy of classification, developed something of a crush on Madeleine, writing in what obviously passed for flirting in 1749, “Send my compliments to my very dear Mlle Basseporte, the ornament of her sex; I speak of her in my dreams and if by chance I become a widower, she will be my wife whether she wishes to or not.” Benjamin Franklin, who was famous not only for his kite and lightning demonstration, but also as the ambassador for the United States in Paris in the late 18th century, was a great admirer and friend of Madeleine, and she entertained him in her house on at least one occasion.

She may have been surrounded by male admirers, but her heart was elsewhere – with Marie Biheron, another women in the field of science who chose the difficult path of studying anatomy and created incedibly lifelike wax models of the body which were feted across Europe. There is scant evidence of their relationship: Biheron wrote to Benjamin Franklin in 1774 to thank him for the “beautiful present” he had given both she and Madeleine the previous year, and she was named executor in Madeleine’s will. In Biheron’s own will in 1795 (she luckily survived the Terror in the turmoils of the French Revolution) she passes on a self-portrait of Mlle Basseporte in a gold frame, which would have been a cherished possession.

Much to the astonishment of her male colleagues, Madeleine continued to work into her seventies. Perhaps it was tongue in cheek that she began to write her age on her botanical art, to deter talk that she was becoming old and senile.

“The works that come to life under her brush are regarded by all the connoisseurs as masterpieces, where art challenged nature for truth of expression, delicacy, and the precision of the coloring. Although presently seventy-eight years old, we still see this indefatigable artist exposed, throughout whole days, to the ardours of the sun, in the most uncomfortable positions, copying for the Cabinet du Roi all that nature offers of the most magnificent, the most precious and the most rare in the plants gathered in the royal gardens.”

1779, Abbé Riballier and Charlotte Catherine Cosson, De l’Education physique et morale des femmes

Madeleine Basseporte died not long after this was published, on 4 September 1780. Her eulogy praised not only her botanical art, her skillfully rendered flowers and animals, but her reputation: “No foreign prince comes to Paris without wanting to marvel at her works and to meet the famous painter”.

She may have been respected for her skills and talents, and was in a sense a role model for women, but she worked for free for a long period of time until a pension was granted (less than the male salary, even when it was doubled in 1774), and she was not invited to join the prestigious Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture where only four women at a time were admitted. There is no doubt she was a woman in a man’s world but she rose above the challenge with dignity and left us her magnificent paintings for all of time.

Further reading

Nina Rattner Gelbart, Minerva’s French sister: Women of Science in Enlightenment France, Yale University Press, 2021