Surely there is nothing more French than a warm, buttery, flaky croissant fresh from the boulangerie, perhaps while savouring a café au lait with a view of the Eiffel Tower. Should you ever find yourself in mid-19th century Paris and craving such luxuries (without the view of the Eiffel Tower, of course), there is only one place to go – Zang’s Viennese Bakery. Wait, I hear you say. Why would a French croissant be made in a Viennese bakery? And herein lies one of France’s best kept secrets: the croissant is not actually French.

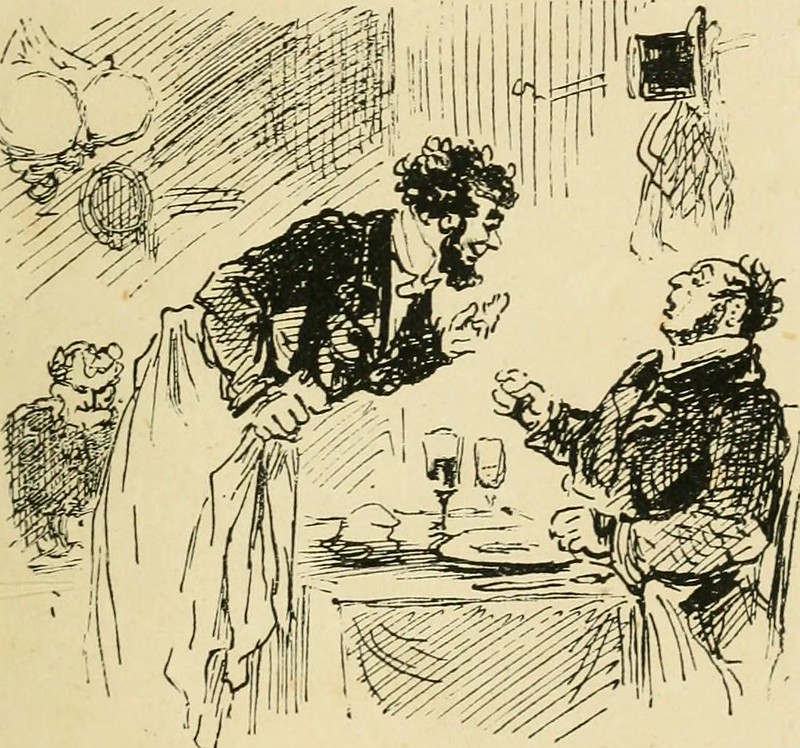

August Zang was a former Austrian military officer who came to Paris in the 1830s to seek his fortune. The story goes that the day he arrived, he sat at a Parisian cafe, and was given a piece of bread to drink with his coffee.

“Do you have any white or soft bread?”, he asked the garçon.

“Non”, was the reply.

“No problem, I’ll have a croissant instead”, he declared.

The garçon said he did not know what was this “croissant”.

“You will know in 6 weeks”, pronounced Zang.

This story is most certainly not true, but there is no doubt the bread made in France at this time, being very much a daily staple, was cheap, coarse and ordinary, and the pastries dull and disheartening. Bread from Vienna, on the other hand, was soft and luxurious. In 1837 several French princes visited the Austrian court and during a formal dinner were introduced to these ‘petit pains viennois’ (small viennese bread rolls). Exclaiming wonder over the lightness and exquisite taste of the bread, the princes declared such baked goods as these would be very popular in Paris.

August Zang opened his Boulangerie Viennoise (Viennese bakery) around 1838 (the exact date is unknown) at 92 Rue Richelieu, one of the most fashionable streets in Paris. With the wafting scent of sweet, soft, cooked dough from the bakery’s hay filled ovens, Viennese bread became an instant success in Paris. The shop was full from morning until evening, with long queues out the door. Zang had a great sense of marketing and installed iron plates with his name into the oven so that all of Paris could see whose bread they were eating because it was branded underneath. He employed more than 50 porteurs de pain, who delivered the bread in carts with Zang’s Boulangerie Viennoise painted on the side.

So how is this related to the croissant? Because historians agree that the croissant is a direct descendant of the Austrian kipfel, a crescent shaped baked good made with lots of butter or lard and sometimes filled with sugar or almonds. Whilst there have been moon shaped breads around for centuries, no one really knows for sure how the kipfel originated.

The most well known legend states that in 1683, bakers working through the night in Vienna heard Turkish invaders tunneling under the city, were able to sound the alarm and hence the siege of Vienna by the Ottomans failed. The kipfel, the shape of the Turkish emblem of the crescent, was therefore created to celebrate their victory. Is this likely? Perhaps, but there have been previous references to kipfel and also to kaiser-semmel (a star shaped bread roll) in history. The German word gipfel actually refers to ‘summit’, and prior to 1519, carved into the summit of the main tower of the famed Saint Stephen’s Cathedral in Vienna, you could see a star (representing the pope) and a moon (representing the emperor). So the two emblems were fairly well known in terms of symbolism long before the Ottomans invaded Vienna.

Another famous story in the history of the croissant is that Marie Antoinette, missing her native home of Vienna, asked the royal chefs to bake her the soft, buttery bread she preferred over the French bread. From this, it is believed, all of Paris became enamoured of the Viennese bread.

The only things of which she was particularly fond were her morning coffee and a sort of bread to which she had grown accustomed during her childhood in Vienna.”

Madame Campan, First Chambermaid to Marie Antoinette

It may be true that Viennese style bread was prepared in the palace, but there is no evidence this bread became popular at this time as a result (nor did Marie Antoinette ever say ‘Let them eat cake’, but that’s another story for another blog).

The short but buttery history of the croissant in France begins then when Zang opened his bakery. It was the talk of the town.

The good croissants? If they exist at all, they exist at Zang’s bakery.

107 recettes ou curiosités culinaires, Paul Poiret, 1928 (the information must have been added to a later edition as the bakery did not open till 1838)

Visiting Paris in 1872–73, Charles Dickens had praise for ‘the dainty croissant on the boudoir table’ and lamented on the ‘dismal monotony’ of English bread and other breakfast foods.

But if you had gone into Zang’s or one of the many viennese bakeries which sprung up in imitation very soon afterwards, the croissant was more like a crescent-shaped brioche, a dense, sweet bread roll rather than the flaky pastry we have today.

The croissant became the modern French breakfast food of today towards the end of the 19th century, when bakers started to use pâte feuilletée (puff pastry) to make their buttery, flaky, yeasty croissant. The technique of making puff pastry had existed since the 17th century in France, but it appears that no baker was inspired to use the technique on the crescent-shaped kipfel until two hundred years later. Other delicious pastries such as pain au chocolat, chaussons aux pommes and pain aux raisins, which the French call viennoiseries, literally ‘of Vienna’, are now as well known as the croissant.

August Zang sold his boulangerie after only a few years, having made his fortune. He returned to Austria where he established the first daily newspaper and invested in mining and banking, and died in 1888.

In 1985, two bakers in Bordeaux came together and set a world record with their rather large croissant. Weighing 21kg, the 3.7m by 25cm, the pastry used 6kg of butter and 12kg of flour, and took three and a half hours to put into shape!

A perfect Sunday breakfast for me in the summer is a warm croissant or pain au chocolat, a coffee, and soft ripe peaches. Sitting outside on the terrace and listening to the birds in the forest. Whomever was the very first person to make the croissant we know and love today, thank you.

Don’t forget to watch my Facebook video where, for the first time ever, with some small helpers, I make my own croissants!

Useful links

This list of best croissants in Paris is from 2017, but it’s useful should you find yourself in Paris and in need of breakfast https://www.timeout.com/paris/en/restaurants/the-best-croissants-in-paris

Or if you prefer pain au chocolat or other viennoiseries, here is a link to a Vogue article of the best bakeries in Paris in 2019 https://www.vogue.fr/lifestyle-en/article/the-best-bakeries-in-paris-in-2019

I love watching episodes of Julia Child’s cooking. Here she is making croissants https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uZmrvEfhfsg&ab_channel=frankensensas