Paris is the city of lights, of romance, of style and fashion. It’s also the place where modern shopping was born. From the resplendent court of Louis XIV down to the busiest of shopgirls, everyone wanted the latest fashions and lacy accessories. As French flair and sophistication spread all over Europe, the fashion-conscious travelled into Paris where, for a price, they could buy themselves social status and have le bel air, the buzzword of 17th century France. So just what was it?

Le bel air, or le bon air, meant ‘the right style’. And the only place you could find le bel air was in Paris.

The French have particularly fine taste, to create an ensemble where everything perfectly matches. The women, especially, possess the secret of being stylish even with very little. They have je ne sais quoi charm, even when wearing only a robe de chambre (dressing gown) and unstyled hair…This is the reason les modes Françaises are copied so much in your country and many other countries.

Joachim Christoph Nemeitz, Séjour de Paris, 1727

17th Century Paris

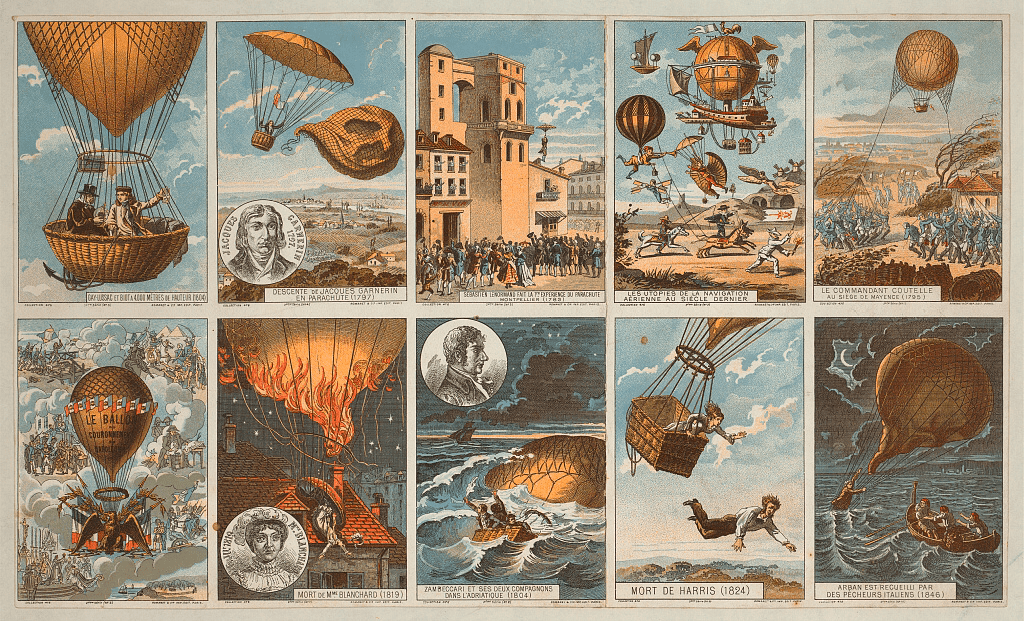

Paris in the 17th century was a city transformed. The wide expanses of the Pont Neuf, completed in 1606, gave Parisians and visitors an unparalleled view of the city from the centre of the Seine river, and enabled easier access from the banks of the left to the right. Streetlights, a first in any European city, meant that businesses could open their doors until late at night and that the well dressed were less likely to have their finely embroidered cloaks, or manteaux , stolen by quick fingered filous in dark and narrow streets. All of Paris congregated in the elegant public space of the Place Royale (now known as the Place des Vosges) or showed off their frilly fashions and polished carriages along the Cours de la Reine next to the river.

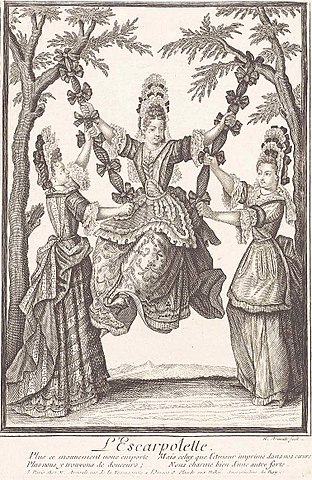

But it was the re-imagining of the gorgeous gardens of the Tuileries by Andre Lenôtre, famous for his landscaping at Versailles, that allowed the latest styles to be showcased, a modern form of advertising. Noble ladies (and men) in French made silks and taffetas, feet enclosed in dainty be-ribboned slippers, strolled and smelled the roses along the wide paths, and rested on newly installed wooden benches. The nouveau riche who had mostly made their fortunes in property dealing and financing war loans from the state, followed the latest fashions, which were copied by anyone of the lower classes who had the money to wear fancy clothes or to add lace to their outfit.

In the previous century, wealthy Parisians bargained for fabrics and books at the upmarket Galerie du Palais, located on each side of the walkway leading to the Great Room at the Palais de Justice on Île de la Cité. A fire destroyed its wooden stalls in 1618 and in its place was built an elegant Renaissance structure. It was an early blueprint of a department store, first of all being indoors rather than an open-air market. Spacious counters showcased each merchant’s goods, and men and women both bought and sold whilst they mingled in the aisles and compared products and prices.

Parisians still bought at fairs and markets and from the peddlars who knocked at their doors, but with the beginnings of the luxury goods industry, the face of shopping was to change forever, from the mundane to the pursuit of pleasure.

Paris as Capitale à la Mode

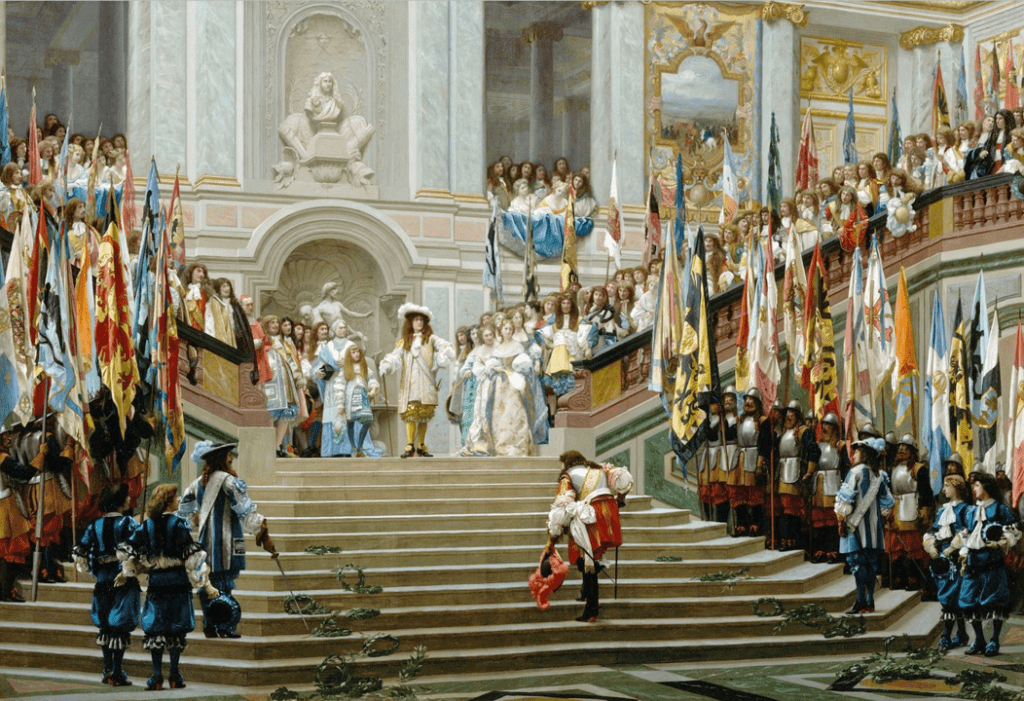

It was a calculated strategy by Louis XIV to make Paris the luxury fashion capital of Europe, the capitale à la mode, in order to strengthen the French economy. And it worked, for the idea of French style, le bel air, that the only dress or accessory worth having was a French one, spread rapidly over Europe. The luxury goods were entirely made in France, and these exports made an enormous contribution to Louis XIV’s royal coffers (which he needed as this century was also riven with civil war and European conflict).

To create this desire for the newest fashion, Louis XIV made sure the latest designs and most beautiful fabrics were first seen at court. The ‘look’ was then created for an exclusive market, which, like today, was really anyone who could afford it. Aristocrats and financiers, courtiers and property dealers alike all strove for le bel air and flocked to the dressmakers and haberdashers of the moment. Retailers learned they could cajole their clients into visiting their shops which were sumptuously decorated and lit throughout with large glass panes, and with fabulous armchairs in which to comfortably repose while making your choice. The art of seduction in shopping was just beginning.

It is mainly the women (shopgirls) who know how to show their merchandise and flatter the buyer… their beauty is often a powerful way to attract customers and to make a large profit. Or perhaps it is in these boutiques that foreigners, new to Paris, are seduced. The flatteries and caresses of these women are enchanting, so to say, while they really only want to take your money.

Joachim Christoph Nemeitz, Séjour de Paris, 1727

And if you have the goods, then people will pay for them. These purveyors of luxe were among the first to implement le juste prix, or fixed prices. This was a time where haggling at the market or bargaining for the best price was the usual method of determining how much to pay. With the innovation of fixed prices, merchants could charge that little bit extra because the people in search of the latest style would inevitably pay.

Models and Magazines

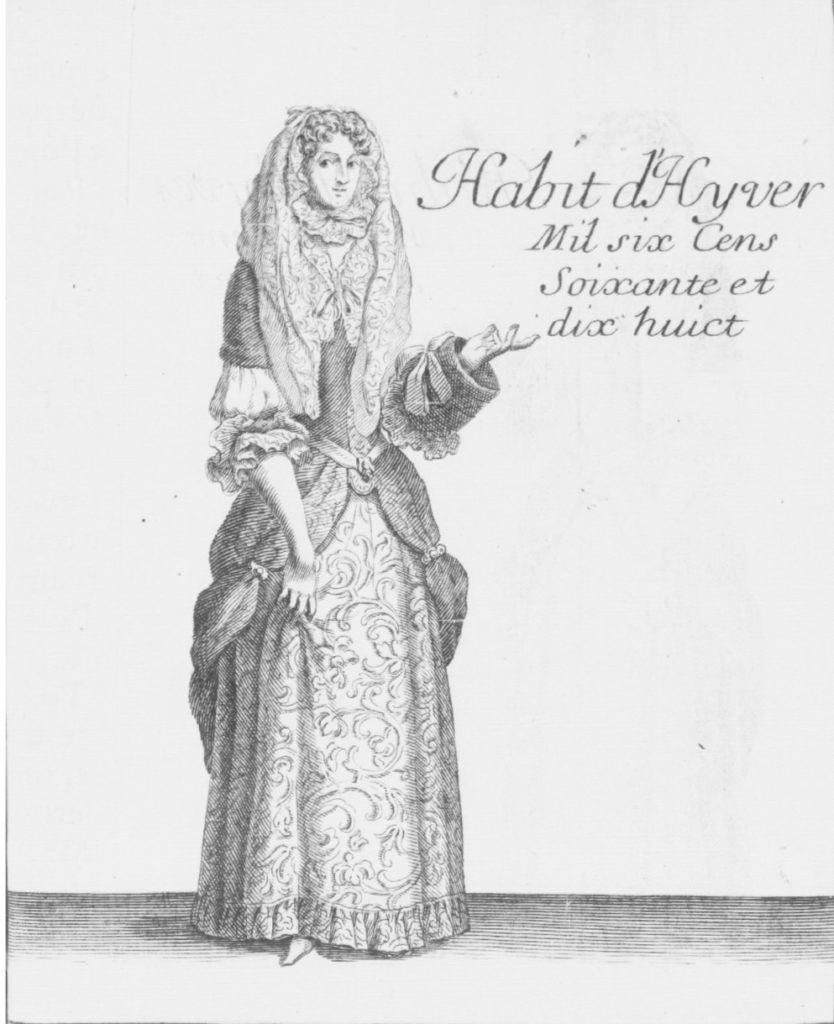

In 1672 a revolution in advertising was begun with the publication of the Mercure Galant, a new journal all about style rather than politics. Its 1678 edition included several illustrations of Paris’ best dressed; a woman and a man in habit d’hyver, or winter outfits. For the first time, the fashion conscious could see images of the latest designs as they happened. The journal, which promoted Paris as the absolute centre of all that was fashionable, was extremely popular in France and soon read all over the continent. Everyone wanted to be dressed and styled à la mode , a phrase which was fast becoming popular.

Artist Nicolas Arnoult became well known for his fashion plates, engraved in the late 17th century. His ‘models’ were illustrated walking or sitting on benches in the Tuileries Gardens, à sa toilette, playing billiards, and in all seasons.

Nemeitz and finding le bel air

Travel guidebooks devoted entire sections to the stores currently in vogue, advising their fashion-hungry readers and travellers that they could have have an entirely new Parisian wardrobe created in a few hours, for a price, of course. Joachim Christoph Nemeitz , writing in Séjour de Paris in 1727, counselled visitors to adhere to the number one rule of French fashion: Do not try to be an individual, dress only in the latest mode.

According to Nemeitz, a (male) visitor to Paris must acquire three habits, or formal outfits. These are a simple habit, a black habit, and a habit chamarré. The simple costume is to be a tightly fitted vest and culotte of the same fabric and colour and without embroidery or silver. The last outfit, the habit chamarré , which meant highly decorated or ornamented clothing, was necessary just in case one would be ‘presented at Court’.

Nemeitz encouraged visitors in search of ‘luxury, vanity and splendor’ in Paris to only buy the goods they can’t get at home. There is no need to buy lace as it is far superior in Brussels, nor should you spend your money on silk stockings or fine underwear as the quality is better in England. In Paris, according to Nemeitz, an epée (sword) is a bel ornament, either in silver or gold depending on your preference, and the best are to be found in the shops on the Pont Saint-Michel. If you have time, the men must have made for themselves a perruque de bonne façon, a wig of the best quality, and for the women, some habits chamarré, beautifully decorated dresses. One hundred varieties of snuffboxes can be found in the best streets, and for a decent price. There is even a large selection of the latest in comfort, ready made robes de chambres, available in clothing stores.

If perchance, you intended to purchase gifts for one or more women back home, Nemeitz advised a visit to the Palace Gallery for all manner of trinkets and jewellery. Here you would find an infinite selection of belles nippes, which include ribbons, collars, embroidered handkerchiefs, lacy veils, fontanges (elaborate headpieces) and fans, which Nemeitz assures the reader will be received with pleasure by the beau sexe.

All about French style

Le bel air wasn’t only about frou-frou and frocks; it encompassed all aspects of living. A century before, your Italian made glassware was the epitome of style, but with the ever increasing locally produced luxury market, only French-made decor would give your salon a certain je ne sais quoi. It was necessary to have beautifully coloured glass ornaments, intricate silverware, bronze figurines and crystal lamps. As for the furniture, there were finely carved wooden tables, the lightest of cotton curtains (the French imported cotton from India) and the latest in comfort, the plush canapé . The design of the living space became of the utmost importance, architects considered the placement of furniture in their drawings for new constructions, and exclusive haberdashery stores became the forerunners of modern day furniture shops.

An early form of advertising was the use of enseignes, a large sheet of paper used to wrap the purchase in which an image or the name of the shop was printed. Walking down the street carrying a parcel from the embroidery shop Magoulet was much the same as being seen today in the Place Vendôme holding a black and white shopping bag with a Chanel logo. Magoulet was the official embroiderer to queen Marie-Therese, the long-suffering wife of Louis XIV, and his store on the prestigious Rue Saint-Benoit was among the first to utilise the concept of desire, to use marketing to create an aura around his ‘brand’.

Edme-François Gersaint, born at the close of the 17th century, was a marchand mercier, or dealer in objets d’art such as furniture, decorative items (mirrors, chandeliers, caskets, clocks), paintings, engravings, and gilded wooden frames. This painting above was created in 1720 by his artist friend Antoine Watteau, and is an early form of retail advertising. Note the open, light-filled exhibition space, the salespeople in noble dress, and the aristocratic clientele. The painting was prominently displayed outside the store and was the talk of Paris for two whole weeks.

By the middle of the 18th century, more than half the stores in Paris sold luxury goods and clothes. Shopping had become a thing, and it was a popular pastime for both men and women. Despite Louis XIV’s outrage, who wanted all women at court to remain formally dressed, over the course of the century women’s clothing became less restricted and allowed for a greater number of constantly evolving designs. Styles changed so rapidly that new outfits and accessories were needed all the time if you wanted to keep abreast of the latest trend, much like fashion today.

Paris may have changed immensely since the 17th century but it is still a city of luxury, it is the only place where one is likely to have le bel air, an innate sense of style. Thanks to Louis XIV, and the innovations in marketing and retail which followed, we have both luxury brands and high street shopping, opulent department stores and quaint boutiques, and the sense of pleasure and satisfaction after a long day of shopping.

What’s your favourite place in Paris for shopping? Tell me in the comments below.

And speaking of shopping, make sure to visit the Shop here on my website, where you’ll find beautiful prints and postcards reprinted from original French books, journals and engravings.

Reference, Joan Dejean, How Paris became Paris: the invention of the modern city, Bloomsbury, 2014.