In 18th century Paris, nine out of every ten newborn babies born were sent away from their family after birth. Some returned, many did not. They were subject to the age-old tradition of wet nursing in France, where babies were not breastfed by their own mother but were given to a wet nurse, another woman who had recently given birth and would feed the child from one to up to four years. Wet nursing was not distinct to France and was practised in other parts of Europe, but France would continue the business of wet nursing into the 20th century.

Wet nursing through the Ages

Wet nursing is one of the oldest female professions. There is evidence of their presence in the Ebers Papyrus (1550 BC) and in Babylonian codes, such as those of Hammurabi. In ancient Greece wet nurses were often domestic slaves responsible for the care of infants well into childhood, and in ancient Rome they could be hired at the Colonna Lactaria in the Roman Forum. Once these Roman wet nurses were hired a contract was drawn up, such as with Didyna who “agrees to nurse and suckle outside at her own home in the city, with her own milk pure and untainted, for a period of sixteen months the foundling Marcus for wages for milk and nursing of ten silver drachmas and two cotyla [pints] of oil every month”. Wet nursing was regulated by the Spanish and French monarchies by the 12th century; a French edict declared in 1350, “Wet nurses nursing children male and female outside the house shall earn and take 100 sols a year and no more”.

The great sculptor, Michelangelo (1475– 1564), attributed his talent to his wet nurse who was a stone-cutter’s wife: ‘With my nurse’s milk I sucked in the hammers and chisels that I use for my statues.’

How to be a Good wet nurse

So what exactly made a good wet nurse, or nourrice? Louise Boursier, the midwife of Queen Marie de Medici, in her 1609 treatise on childbirth titled Diverse observations on sterility, miscarriage, fertility, childbirth, and diseases of women and new-born children wrote:

“The important thing to consider is her gaze, such as whether she looks directly at you, is cross-eyed, or looks downcast. This is important, because she will look at the child. Take care that she is not a redhead, because their milk is very hot […] Observe whether her teeth are white and well set. […] Find out if any bad odor comes from her nose, for the least strong smell emanating from a wet nurse’s nose or mouth greatly harms the child’s lungs, in the same way that the vapor rising from mud or a privy can spoil bronze, copper, or silver and blacken it. […] A wet nurse should therefore be pleasant, have good teeth, dark or brown hair, and come from a healthy family. […] She should not be choleric; she should have good, abundant milk. Her nipples should not be too thick, for this often makes it difficult for the child to nurse. She should not be too fat, and above all, make sure she is not of an amorous disposition. This is often the case with honest women whose disposition causes them to lie with their husbands. Their milk is then true poison for a nursing child. This can be seen when they nurse a child, for their monthly purgations start up again very early on. Truly good wet nurses never have them while nursing, or at most they have them fifteen or eighteen months after giving birth. I have observed that when they have them earlier, the children languish from that time on”.

In a later chapter she expounds on the quality of the breast milk, which should be examined with the eyes and tasted with the mouth: “it should be white with a pleasant appearance, taste and smell, of moderate consistency and of correct age (two or three months, at the best). The consistency of the milk should be tested by tasting it after letting a drop roll on the nail; the best, moderately thick milk spreads gently: it is sugary and tastes like almonds. Watery milk runs off immediately and the child is poorly nourished; thick milk stays together and remains motionless: “Children who are nursed with this kind of milk are sicklier in childhood than their parents in their old age”. Salty milk is “more livid in color” and is “poisonous” for children.

There was a strong belief that the physical and moral qualities of a woman would pass through the breastmilk to the child, so she must also be of a good character. And, for obvious reasons, free of syphilis, which was an up and coming disease in the 17th century.

The Royal Nourrice

Wet nurses were always found within the households of French royalty. The royal nourrice was chosen several months before, as well as a few replacements in case of a disrupted supply of breastmilk. Louis XIV, the Sun King, went through eight wet nurses, whilst his great-grandson Louis XV was lucky enough to only need one through his babyhood, Marie-Madeleine Mercier, who successfully nursed him for eighteen months. These nourrices usually stayed close to their royal charges in some way, most went on to become wealthy and moved up the social ladder to positions of importance. When Louis XIII’s 13-year-old sister Elisabeth married the Infant Felipe in November 1615, she travelled to the Spanish court with her nurse and kept her in her entourage for six years until December 1621 when, after becoming Queen Isabel, she sent her back to France with a generous gratuity.

Louis XIII, the son of Henri IV, sits on the knee of his wet nurse, Antoinette Joron, whom he called Maman Doundoun. She was the fourth wet nurse, and there were initially concerns: “little milk, we are quite upset…in several gulps he emptied a breast.” Nevertheless, she improved and nursed the dauphin until he was weaned aged 2 years and 1 month. She stayed with him for many years afterwards.

Cities without babies

Wet nursing was a thriving occupation throughout Renaissance Europe and beyond, but it is a common perception that it was just for royalty or the offspring of the wealthy elite. In fact, in the 18th and 19th centuries in France, Paris and other large urban areas were referred to as “cities without babies” as a huge majority of newborns were sent to the outskirts and surrounding country areas to be fed and weaned by wet nurses, often until the age of three or four. Artisans, shopkeepers, factory workers and even domestic servants gave their babies to other women to be breastfed (or given animal or milk substitutes), despite its inherent dangers and resulting high infant mortality rates. There was an enormous difference between the wet nurses of the well-to-do artisans and the poorest of the poor rural women catering to the babies of the lower classes.

A Royal Decree of 1715 had declared the ‘protection of children’ to be a national cause and by the 1730s of about 19,000 babies born in Paris almost half (about 9,000) were placed with distant wet nurses. 50 years later, according to Jean Charles Pierre Lenoir, lieutenant general of the police prior to the French Revolution, of the 21,000 babies who were born in Paris in 1780, only one thousand were nursed by their own mothers – which means over 20,000 were nursed commercially. Lenoir’s figures indicated that 15,600 were sent to the countryside with rural wet nurses, and the remainder were nursed either in the Parisian suburbs or in Paris itself with live-in nourrices.

All Paris, with the exception of nobility and beggars, participates in this migration of newborns towards the pure air of the country

Dominique Risler, historian

Wet nursing in France

It is tempting to view the past through the eyes of our own century, when for most of us it is inconceivable to give our babies to be raised by another woman. Did the mothers of the past not love their infants? Were parents indifferent in a time of high infant mortality? Was this ‘children must be seen and not heard’ taken to the most extreme level? In discussing the issue of breastfeeding which is polarising even today, when women are told ‘breast is best’ , it is important to see the custom of wet nursing in France in its context.

There were important cultural norms of the time. For upper class women there was an expectation of maintaining beauty and social status, as well as keeping their husband satisfied as demanded not only by the men themselves but also the Catholic church – difficult to manage with a newborn at your breast. Louis XV, who had over fifty mistresses in his long reign, apparently detested the idea of a woman daring to use her breasts to feed her child. If you’ve ever wondered how the nobility and wealthy women could have had so many pregnancies in the past, it is because their bodies were not producing the milk which can act as a contraceptive.

Diane of Poitiers (1500– 1566), who was a favourite mistress of King Henry II of France, takes a bath while a wet nurse suckles her baby. The painting makes it clear that feeding babies was not the job of a royal mistress, whose breasts were reserved for the pleasure of the king.

There was also something of an apathy towards children which we have difficulty in comprehending today – families had many infants, few survived past childhood, and for the lower classes in uncertain times of famine or poverty children were more of a burden than a blessing. Babies were often abandoned to foundling hospitals and children were commonly subject to neglect and beatings. It is certainly true that “good mothering is a result of modernisation”.

The countryside, with its fresh, clean air was viewed as a far better place to raise children than the overcrowded, disease-ridden streets of Paris; parents who sent their babies away were perhaps trying to protect them from the dangers of a large city.

Working Mothers

But cultural considerations play only a small role in the history of wet nursing in France. For most families, it was purely an economic necessity. When Louis XIV embarked on his ambitious plan to make France the economic powerhouse and fashion capital of Europe through textile production, there was a subsequently large urban population engaged in manufacturing and retailing, many of them women. The French capital was full of small businesses and workshops that employed young women as seamstresses, shop-girls, domestic servants and artisans. Lyon was a major industrial centre, with silk woven on handlooms, mostly by women, in thousands of small independent workshops. There was nothing new about mothers working but with a population explosion in 19th century France jobs in the rural areas were scarce and thousands flocked to the cities. Many more women were now working in urban shops and small apartments, that is, in settings where it was impossible for them to nurse their babies. Women whose husbands worked in newer industries such as the railways were more likely to breastfeed their own infants. France was somewhat slow to wages were low and rents high, but it was still cheaper for working women to send their newborns to a poor peasant in the countryside than to stop contributing financially to the household. Babies were usually returned (if they were lucky) weaned, walking and toilet trained.

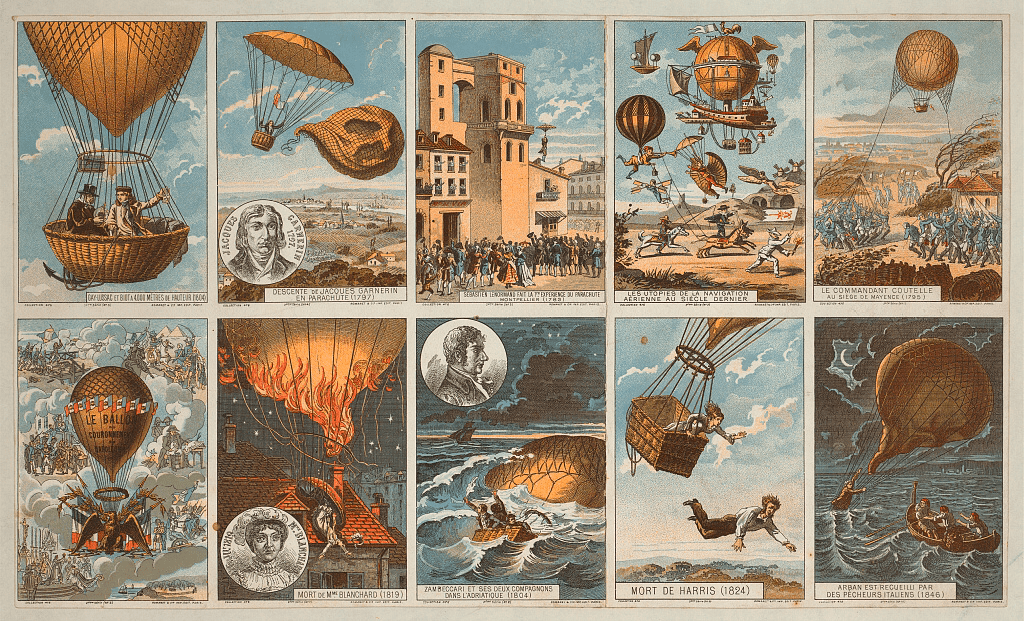

The enormous movement of babies to and from Paris and the resources required became the responsibility of a Municipal Bureau des Nourrices, established in 1769 under the control of the lieutenant general of police. Licensed recommandaresses had exclusive rights to control the supply of wet nurses in Paris, and intermediaries called meneurs or meneuses were the links between parents and wet nurses, organising the transfer back and forth of infants, payments, packages, clothing and messages. Experienced nourrices employed by wealthy families could expect 24-30 livres per month and were provided with meat, wood and further remuneration at the baptism and the end of the contract. It was often financially worth their while to give their own babies to another nurse at a lower price and therefore work for longer as a wet nurse.

The Bureau des Nourrices also instituted a new system in which they paid the wet nurses directly. Wages were often slow in coming or not paid at all by errant fathers, so the Bureau used police resources to collect debts or imprison those who didn’t pay. When Marie Antoinette publicly announced her first pregnancy, she gave 12,000 francs to send to the relief of those languishing in the debtors’ jail for failing to pay their children’s wet-nurses. “Thus I gave to charity and at the same time notified the people of my condition,” she wrote to her mother.

Wet nurses came mostly from the departments surrounding the city, Normandy, Picardy, Champagne and Burgundy, and they were ‘ordinarily very poor’ and suckled their own babies for six to ten months before taking on a position as a wet nurse. As the demand for wet nurses in Paris grew, there developed a traffic not just of babies from town to country but also of wet nurses from country to town, often under duress. A contemporary source tells us: “These women are conducted to Paris into domiciles that do not seem ever to have been intended to receive human creatures. They are huddled together in miserable offensive rooms, without air and where even there are not cradles for the infants. It is to such persons, and in such places, that a great part of the Parisian population confines its children; no wonder that the mortality should continue beyond all proportion in early childhood”.

At what cost?

The babies themselves more often than not paid the ultimate price. Abandoned infants, whose prospects were already dismal, were taken in by the Paris Foundling Hospital where the mortality rate was around 69 per cent due to overcrowding, lack of ventilation, malnutrition and epidemic diseases. They were often given laudanum to keep them quiet and sometimes sold to professional beggars who used them to inspire pity and donations. Those that could not be kept in the hospital were divvied out to the poorest and cheapest of all the wet nurses, and as these women usually lived the furthest from Paris, up to 90% of foundlings died on the journey. Even more died of starvation when a peasant woman tried to feed more than one baby or of illness or disease in unsanitary conditions.

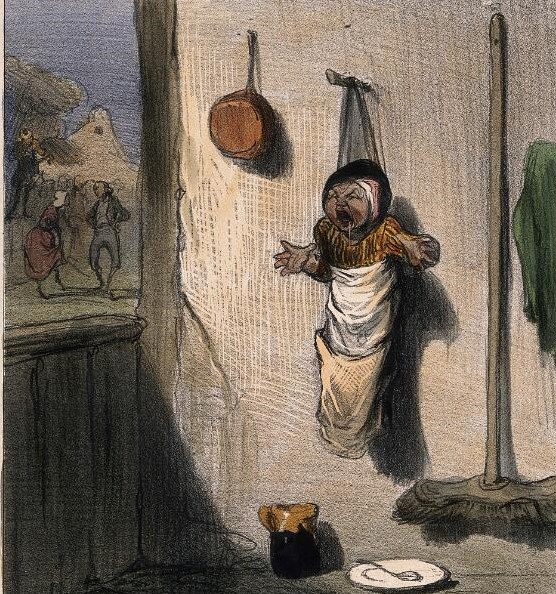

The caption on this cartoon from 1850 read:

The Heir Apparent

The first philosophy lesson given by the wet nurse Jabutot to her student, while she engages in dancing, is to give him a glimpse of the difficulties of maintaining a social position, and teaches him that in the course of his life a man sometimes remains in suspense..

Humourous, but the reality was that many children suffered neglect and abuse at the hands of their nourrices.

But the babies of the elite were not guaranteed a path through childhood. The wife of Claude Le Doulx, counsellor in the Parlement of Paris, had 13 children from 1671-1695, only 3 of whom survived past their first year; the child who lived until 16 months “died by the fault of the nourrices, among others the last, who did not have enough milk”. Madame Roland who would stand bravely before the guillotine in 1793, wanted to breastfeed her own newborn because she was the only one of her six siblings who survived, “all the others died while out to nurse or in coming to the world”. Of 66,259 Paris nurslings sent to country wet nurses between 1770 and 1776, a third were dead by six months.

Breast is Best, 18th century style

The mother is the baby’s natural nurse, as the father is the child’s natural tutor.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

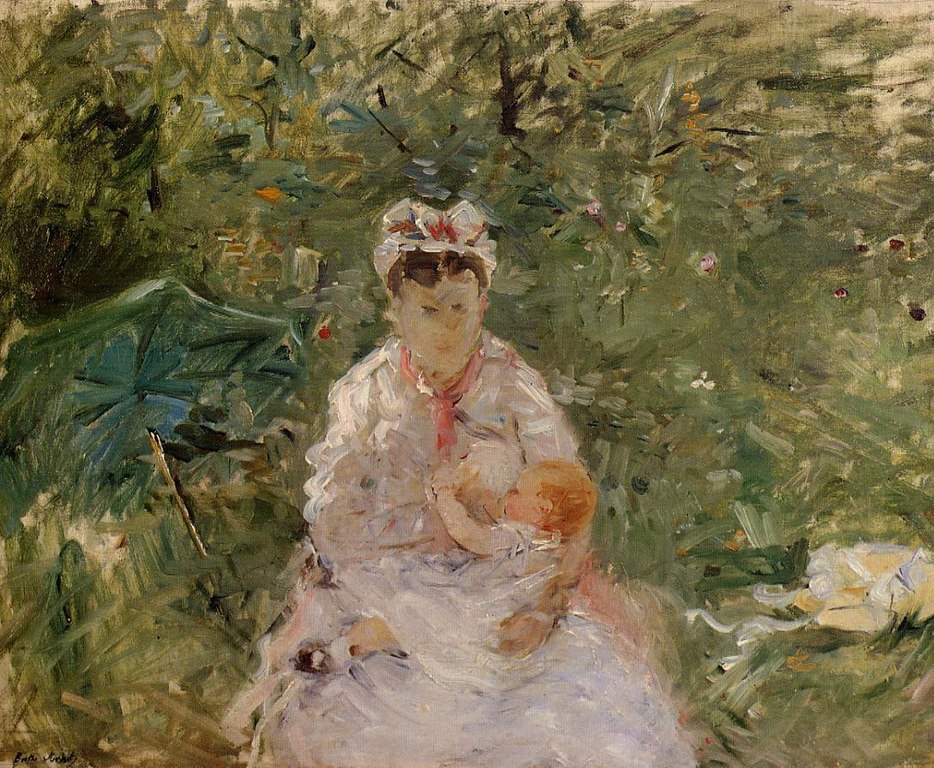

Upper class women began to change the trend of wet nursing in France towards the end of the 1700s, no doubt influenced by the writings of Swiss philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Rousseau had many ideas about infant care such as limiting the use of swaddling and allowing loose clothing to be worn, and his 1762 book Émile, ou De l’éducation advocated maternal breastfeeding rather than wet nursing. Rousseau had rather strong notions about the place of women in the home we would take offense at today, but his beliefs in the importance of the mother’s milk in the formative years were already held by most midwives and doctors of the time. Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus, a practicing physician whose seven children were breastfed, published an important work in 1770, translated into French, which emphasized how natural it was for humans and animals to suckle their own infants. He believed wet-nursing violated the laws of nature and deprived newborns of the colostrum in their mother’s first milk.

As the Ancien Regime came to a close, some upper class and bourgeois women who could breastfeed, did. Marie Antoinette, who waited eight years after her marriage for her first child Marie Thérèse, breastfed her daughter for possibly several months, as she wrote to her mother in Austria that at four months she still had milk in her breasts. The Marquise de Bombelles , lady-in-waiting to the sister of Louis XVI, Madame Elisabeth, breastfed her newborn known only as “Bombon”, and wrote in 1781: “I scarcely have the time to suckle him” with the demands of busy court life at the Palais de Versailles.

Mothers reclaim their babies

France is nearly the only country where the where l’industrie des nourrices (the wet nursing business) is organised. Among other nations, maternal nursing is the rule, even among the well-to-do classes.

Delore . 1879

As the practise of wet-nursing declined over the rest of Europe in the 19th century, it was still widely accepted in France until the 20th century. Historian George Sussman believes this is why:

“French cities grew rapidly in the nineteenth century because of the rural population explosion. Industrialization, on the other hand, occurred much more slowly in France than in other West European nations. The combination of rapid urbanization and slow industrialization produced the special conditions of many French cities: high rents and low incomes for the working class and the persistence, indeed the expansion of the traditional household, which was a small unit of production for the market as well as the setting of family life. As a result of these conditions and the work roles they imposed on working-class wives, increasing numbers of women were unable to suckle and care for their very young children. Since this pre-industrial urban growth occurred before the development of safe methods of artificial infant feeding and, for the most part, before the decline of popular fertility, it was in turn responsible for a crisis in infant feeding which inevitably took its toll in infant lives. Wet-nursing was the particular solution to the problem of feeding the infant children of working mothers which was adopted in older French cities, where the upper classes had long put their children out to nurse for different reasons and had left behind attitudes and institutions which were favorable to the practice. “

Only in the late nineteenth century did the discovery of the germ theory and a technological revolution in the production and marketing of cow’s milk make artificial or bottle-feeding a safer option for working mothers. However, this also led to a decline in breast-feeding in general, and data from 1889 shows that only 34 percent of infants from Paris placed with wet nurses were being breast-fed, and 7.5 percent in 1913.

The chaos and disruption caused by WWI saw wet nursing in France almost stop completely, as it interrupted commerce between city and country and created enormous shortages of transport. But why did it not resume as the war ended? The post-war period was one of a general decline in female employment, so more women were able to raise their infants at home. There was also fewer rural women who were willing to undertake the task – times were changing. Several laws were introduced to encourage breastfeeding – in 1917 allowing women allocated time to feed their children in the workplace; and in 1919 giving an allowance of 15 francs per month for one year to breastfeeding mothers. Wealthy families often employed live-in nurses, and child care centres or nourrices provided day care for working mothers.

By the 1920s, wet nursing in France had all but disappeared and was relegated to the history books. It’s a fascinating insight into changing attitudes towards health and family over the centuries.

Principal sources

George D. Sussman, Selling mothers’ milk. The wet-nursing business in France 1715–1914, Urbana, Chicago, and London, University of Illinois Press, 1982

Trevelyan, Weaver, Lawrence. White Blood : A History of Human Milk, Unicorn Publishing Group, 2021.

This was fascinating, especially the fact that this was one of the few ways women could climb the social ladder.