I’ve always wanted to go to a restaurant, raise my hand languidly and say “Waiter, a bottle of your finest Dom Perignon”, as if it were a regular occurrence. Ufor the average person, like me, this is likely to remain a dream.

So, champagne. Not sparkling wine, I mean the real deal. The Champagne region in the north east corner of France has long been known for its superior wines. Even Henry VIII kept his own vineyard in the region. However, contrary to popular myth, champagne was not actually ‘discovered’ in Champagne.

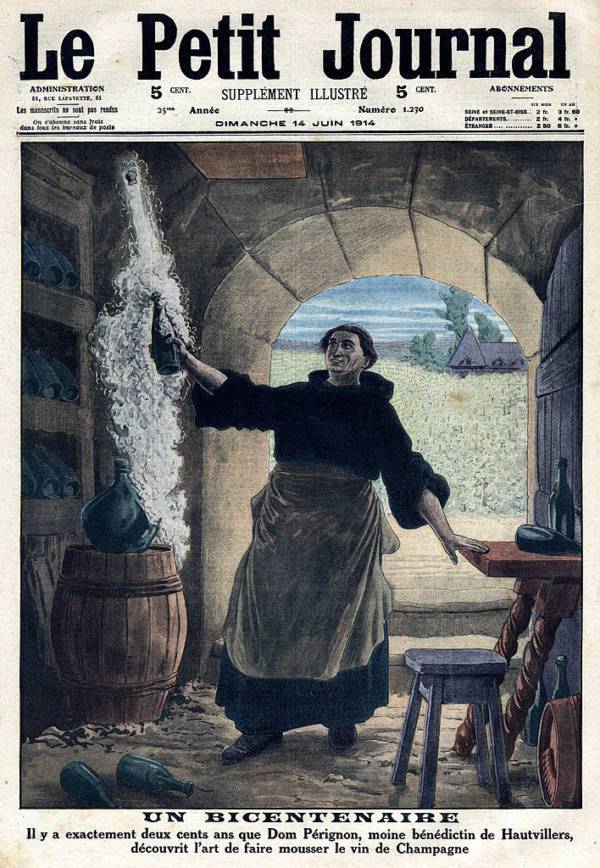

The story generally goes that there was a monk by the name of Pierre Pérignon, AKA Dom Pérignon, who was the cellar master at the Abbey Saint-Pierre d’Hautvillers near Épernay in Champagne during the late 1600s. He was blind and possessed an amazing sense of smell and of taste, and it was said he mixed various grapes from different vines together to improve the taste of the wine and created bubbles in wine by accident. On drinking this sparkling wine for the first time, he is said to have exclaimed, “I am drinking the stars!”

Now we know much of this story is fiction. Pérignon did exist and was the cellar master at the monastery, and made important advances in the production of wine. In the 1820s, Jean-Baptiste Grossard, a monk at the same monastery, apparently made up the story that Pérignon had invented sparkling wine as a way of embellishing the reputation of the church. This story was widely accepted as true until the late twentieth century.

As for the ‘invention’ of champagne, it seems it invented itself:

All wines start to bubble the moment grapes are pressed, Yeast on the skin comes into contact with the sugar in the juice; it is converted to alcohol and carbonic gas, a process known as fermentation. In cold regions like Champagne, yeasts go into hibernation during winter before all the sugar has been converted. In spring, they wake up and resume attacking the unconverted sugar, resulting in more alcohol and carbonic gas, later rising to the surface as bubbles.

Don Kladstrop, Champagne: How the World’s Most Glamorous Wine Triumphed Over War and Hard Times, Harper, 2005

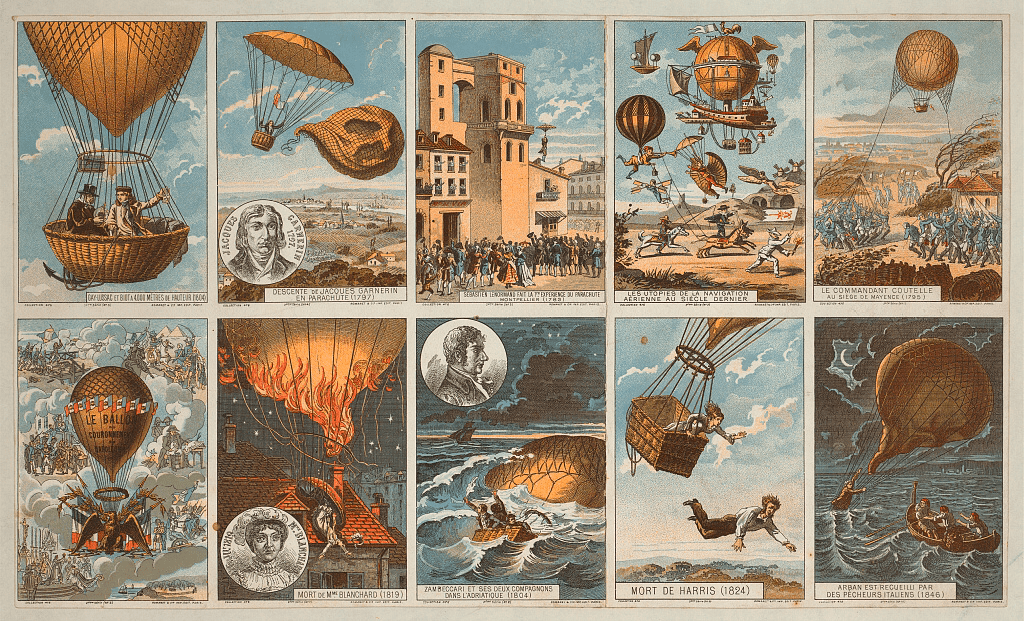

Sparkling wine is known to have graced tables since Roman times. In the north of France, effervescent wines were produced in the Middle Ages. A lot further south in the Languedoc region, as early as 1531 Benedictine monks at the Abbey of Saint-Hilaire wrote about a sparkling white wine that had undergone a restarted fermentation in a bottle.

In fact, for a long time bubbles in wine were seen as a fault. Bottles often exploded with the pressure caused by the fermentation, making it dangerous for anyone in the closed and dark cellars. Wine that fizzed was not at all suitable for mass, nor for most people who preferred still wine. Dom Perignon actually spent much of his time trying to remove the bubbles in his wine, as the climate of the Champagne region made for great fermentation. There was no knowledge yet of the role of yeast in the process, this would not happen for another couple of centuries, with Louis Pasteur.

But regardless of whoever was the first to enjoy it, the region of Champagne was certainly the first to make it popular. The rarity of sparkling wine made it both desirable and expensive, and it was soon a sign of a luxurious and wealthy lifestyle in both England and France.

The Abbey Saint-Pierre d’Hautvillers, formerly the home of Dom Perignon, became the property of:

Messrs. Moët and Chandon, the great champagne manufacturers, who maintain them as a farm, keeping some six-and-thirty cows there with the object of securing the necessary manure for the numerous vineyards which they own here-abouts.

Henry Villezy, Facts about Champagne and Other Sparkling Wines: Collected During Numerous Visits to the Champagne and Other Viticultural Districts of France and the Principal Remaining Wine-producing Countries of Europe, 1879

So it is quite fitting that the most well known champagne in the world should be named Dom Perignon. The first vintage was produced in 1921.

As the end of the 20th century approached, champagne became the focus of anxiety that was, for some, even greater than that caused by the ‘millenium bug’, a computer problem in which people feared all computers would crash and planes would fall from the sky. The worry was that there would not be enough champagne for everyone who wanted to celebrate the advent of the new millennium. There were many media reports that champagne sales had started to increase early in 1999 and that by the end of the year it would be impossible to buy many brands such as Moët et Chandon’s Dom Pérignon. But with great foresight, the champagne houses had actually been preparing for years, setting aside stocks that would be shipped around the world for the millennium.

In 1999 , a record 327 million bottles of champagne were sold, an increase of 35 million over the year before. This was possible because the champagne houses had managed their reserves throughout the 1990 s. Healthy harvests in 1992 , 1993 , and 1994 enabled them to put aside tens of millions of bottles, and even though they had to release some to compensate for a low crop in 1997 , they were still able to put on the market seventy-four million bottles from their reserves at the beginning of 1999 . The result was that despite significantly increased demand in champagne’s export markets, there was more than enough to go around.

Phillips, Rod. French Wine : A History, University of California Press, 2016.

For which special occasion have you popped a bottle of Dom Pérignon?

Thank goodness Don Perignon wasn’t successful in removing the bubbles from his wine!!! I may join you when you crack open a bottle of champagne but not until 2021!!!

We should definitely splurge on a bottle of Moët & Chandon!