A traveller may leave the London Bridge Station at 7.40 on a Monday morning, by mail train for Paris, and be at Nice or Menton for supper the following day.

J Bennett

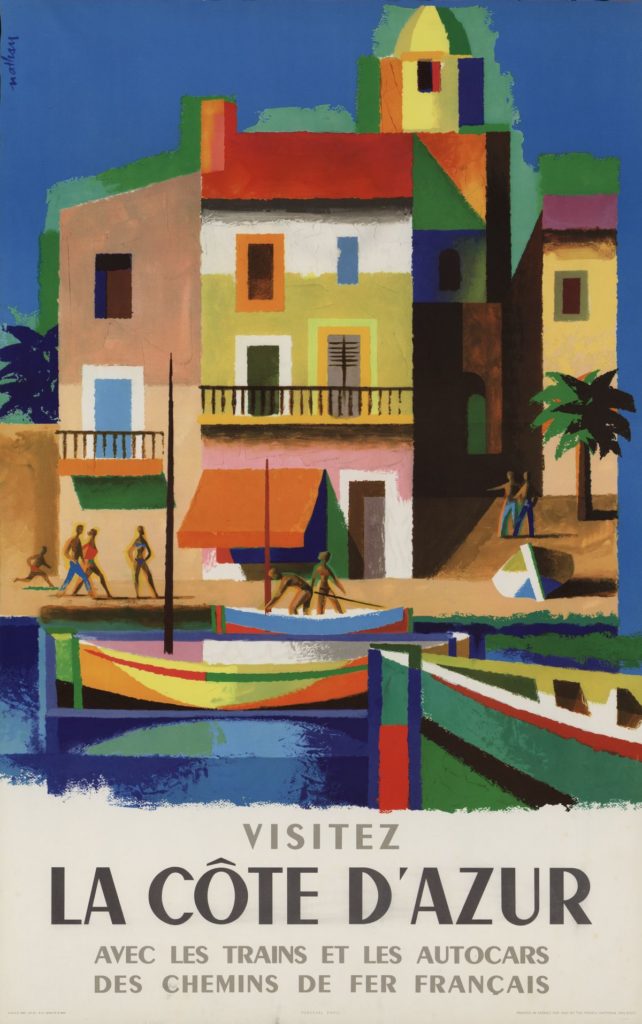

By the end of the 19th century, the French Riviera was THE place to go in winter. The dreary, grey skies of London were only for those who could not afford to leave; the wealthy (and daring) packed their bathing costumes and their lightest clothes, and headed down to Cannes, Nice or the lemon-scented Menton for the season.

The English ‘discover’ the Riviera

Retired English statesman Lord Henry Brougham had ‘discovered’ the area in the winter of 1834; en route to Nice with a consumptive daughter, he decided the weather at the little fishing village of Cannes was “as mild as Cairo” and within weeks had commenced building a grand Regency mansion on a hillside covered with pine trees and an orange grove. He wintered there for the remainder of his life, enjoying:

The delightful climate of Provence, its clear sky and refreshing breezes, while the deep blue waters of the Mediterranean lay stretched before us; the orange groves and cassia plantations perfumed the air around us, and the forests behind, crowned with pines and evergreen oaks, and ending in the Alps, protected us by their eternal granite, from the cold winds of the north.

With the arrival of the railway in the 1860s it was not only the invalids journeying to the sparkling waters of the Côte d’Azur. By 1900 there were well over 100,000 fashionable visitors in Nice at the height of the season, which began in January and ended promptly on 1 May. Newly built hotels and casinos appeared by the sea, and Italianate villas competed with ancient olive tree groves on the rocky hillsides.

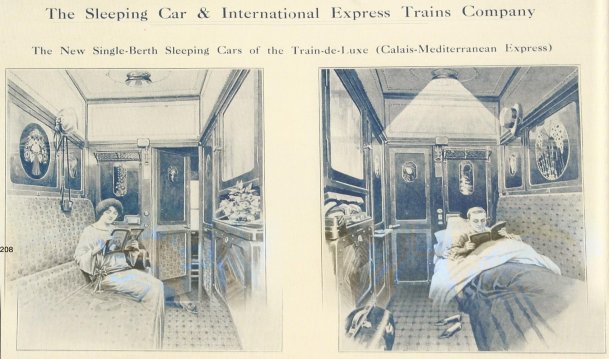

1893 saw the inauguration of the weekly Calais – Mediterranée Express, composed entirely of sleeping and dining cars, as though there was nothing else in life to do.

Riviera, Jim Ring

Le Train Bleu

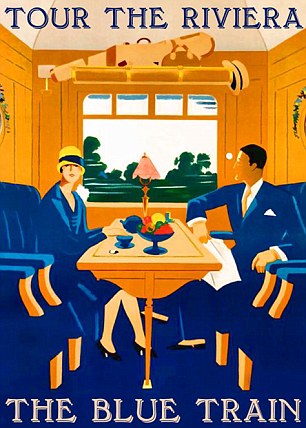

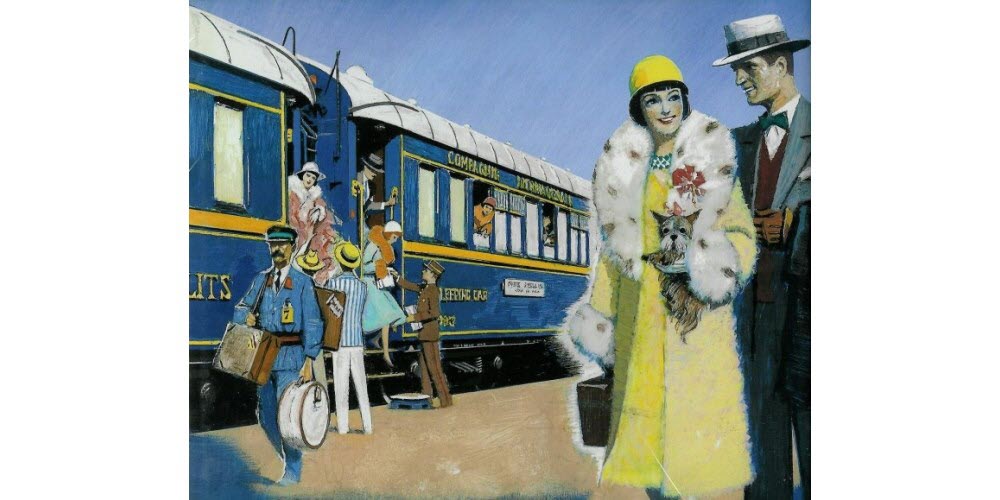

With the roaring twenties came a new style of travel – Le Train Bleu. Inaugurated in 1922, it was the same Calais–Mediterranean Express, but with a serious upgrade. Exclusively first class, its exterior was pure luxury – the steel carriages were painted dark blue and edged with golden trim. This was not a train for the unwashed masses (that would come later), but for the privileged. Such was its clientele, it became known as the ‘Millionaires’ Train’.

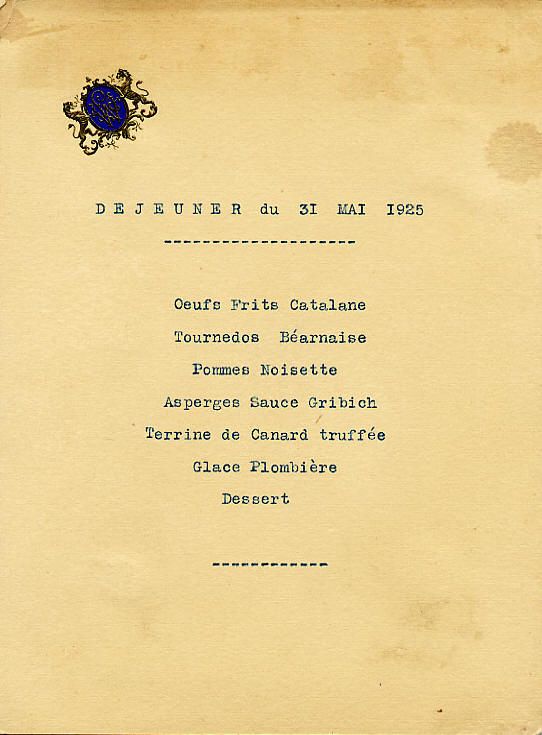

One would merely take the boat train from London and travel across the Channel from Dover in the fog and gloom of an English winter’s morning, board one of the new deluxe carriages, and at 1pm sharp the long train blew its whistle and departed from the Gare Maritime in Calais. Briefly stopping in Paris at the ornately decorated Gare du Lyon in the early evening, the train to Nice and Menton was on its way by nightfall. For the passengers, there were cocktails and champagne in the salon-bar, and dinner in the fully bedecked dining car was an elegant affair. The china dinner setting was white instead of the usual blue, with a gold-leaf motif. Fresh flowers adorned every table.

This menu is taken from a journey on the Orient Express in 1925, but the meal would have been similar, as befitted those used to fine dining…

Then it was time for a drop of brandy before retiring to bed. There was room for merely eighty first-class passengers in connecting luxury compartments, which were panelled with wood and equipped with everything from heavy folding metal washbasins to hooks on which to hang keys. There were more than likely shenanigans and much sleeper-car hopping, but new technology had created the smoothest train journey yet so that these wealthy travellers could enjoy a night of undisturbed sleep.

When (American composer and songwriter) Cole Porter and his wife went south they booked a complete car, with a bedroom for each of them and two more for a valet and maid, a drawing room in which to take their meals and another for work or entertaining.

Chanel’s Riviera, Anne de Courcey

When the privileged passengers awoke, the bleak and colourless skies had disappeared, replaced by ever increasing sunshine as the train trundled south to Nice. Once the aptly named ‘train of paradise’ reached the ancient Greek port of Marseilles, from the window could be seen cascading bouganvilleas and palm trees, terracotta roofs and the dazzling turquoise waters of the Mediterranean Sea.

The train travelled at speed along the coast, finally reaching Cannes, Nice, Monte Carlo and Menton. The elite passengers would be comfortably installed in their white hilltop villa or hotel by the sea in time for cocktails.

So who could afford such a journey?

The Prince of Wales, most famous for abdicating the English throne after less than one year as Edward III, was a frequent visitor, and even added his own personal carriage to the Train Bleu for some royal comfort. An inveterate playboy, he loved the freedom and the joie de vivre of the French Riviera, but especially so as it was here he met future wife, the American Wallis Simpson. It was also here that Simpson fled when news of their relationship broke like a dam in the public press in 1936, and where they took refuge for much of their married life.

The Duke of Westminster, cousin to the King and the richest Briton, travelled on the Blue Train to meet one of his enormous and expensive yachts moored at Cannes, either the reformed destroyer Cutty Sark or his schooner Flying Cloud, where he would spend his winter hosting fabulous and decadent parties or gambling in one of the many seafront casinos.

Gabrielle ‘Coco’ Chanel, lover of the Duke of Westminster and trendsetter, loved the French Riviera. Her villa La Pausa, high on the cliffs of Roquebrune-Cap-Martin and with a panorama along the entire coast, was her retreat from the world. But when she left the Riviera in 1923 she took something with her which created a revolution – a suntan. The Côte d’Azur was no longer only a place to escape the dreariness of winter; the Summer Riviera was born.

Summer living

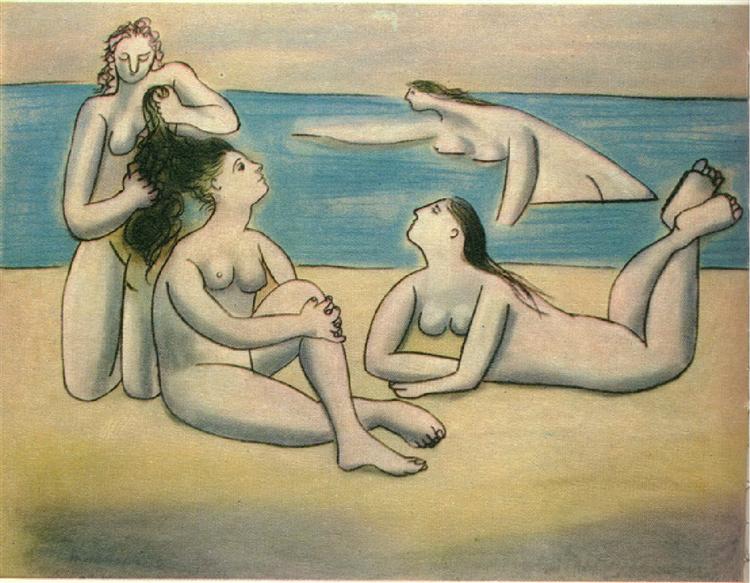

Chanel was not the first to embrace summer living on the southern French coast, but she was one of the most famous. Pablo Picasso had also discovered the joys of the Riviera in summer several years before, and it was in 19020, in the tiny village of Juan-les-Pins on the Cap d’Antibes where he painted the monumental piece of art, Baigneuses, or ‘Bathers’.

Later that summer writers Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas exchanged the stifling heat of Paris for the cool breeze of the Mediterranean, and journeyed down the coast by Blue Train to stay with Picasso.

{Related post: Famous French Lovers}

An idle life

“It is easy to be idle on the Riviera”

Strictly Personal, Somerset Maugham

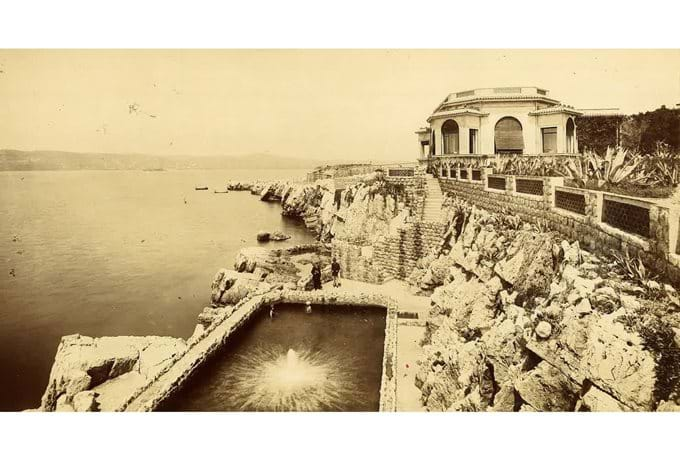

On Cap Ferrat, the best-selling British novelist, Somerset Maugham, lived in stately opulence at La Mauresque, the villa originally built by King Leopold of the Belgians. He had become a millionaire through his writing and at his beautiful Cap Ferrat villa he lived an exquisite life style. The large white house, built around a patio with a terrace overlooking the Mediterranean, the lovely garden, the pool with a Bernini fountain at one end was the perfect setting for the sophisticated and successful man of letters. Here Maugham wrote, golfed, played bridge, and entertained. All the famous people passing through the Riviera came to his villa La Mauresque.

Arrival of the Americans

The 1920s saw American tourists with a strong dollar and an enthusiasm for swimming and tanning burst upon the beaches. In the summer of 1924, American writer F.Scott Fitzgerald and his wife Zelda climbed aboard the Blue Train to Nice. They were the ultimate glamour couple of the Jazz Age, the epitome of grace, glamour and success, and their presence helped to make the Summer Riviera fashionable.

“All was quiet on the Riviera, and then the Fitzgeralds arrived. Everybody was waiting for them and talking about them. The day they appeared on the beach, sunburned from tennis, the summer season was open”.

The New Yorker, 1926

The haunt of American movie stars and the English aristocracy, the sea pavillon of Eden Roc, part of the luxurious Hotel du Cap d’Antibes, was the place to see and to be seen. In his short story “The Three Fat Women of Antibes,” Somerset Maugham writes that the Eden Roc bar was known to everyone as the Monkey House since it was always “crowded with chattering people in bathing costumes, pyjamas, or dressing gowns.” According to French journalist Albert Flament, these were crazy times around the swimming pool, which had been hewn into the rocks in 1929:

Nothing is heard around the pool or in the bar but English. He sees an Englishman swimming with his monocle. American movie stars show off by diving from the highest rocks. Bar waiters in white uniforms serve drinks to the guests lounging at poolside. On a pair of rafts fifty meters from the shore, swimmers lie tanning. Farther out, they are aquaplaning – the newest water sport introduced from America. After swimming, the tanned women don pyjamas or short peignoirs and shade their faces with the newest fad – small, multi-coloured Japanese parasols.

The Riviera is Depressed (briefly)

The effects of the Wall Street Crash in 1929 were soon to be felt all the way to southern coast of France, and only the wealthiest Americans could afford to stay. The British were not be defeated though; titled English were as prevalent as ever at Cannes, and the elegant Blue Train continued its daily departures from Calais. The harbour at Cannes resembled a British colonial port with all the yachts flying the Union Jack.

By the mid-1930s the economy had improved enough that the Blue Train to Nice was full once again. There were women in twos or threes, superbly confident and fashionably dressed, seen daily stepping off the Blue Train, disembarking from a liner, or pulling up in long, low sports cars in front of deluxe hotels.

The 1930s were the golden age of the Riviera in its modern sense – a place to visit for its long, sublime summer rather than for winter warmth. Not yet smothered in concrete, it was at first known as a place to live simply and cheaply, with the rich and fashionable swarming to Antibes, Nice and Cannes, driving out at night along the coast to eat at one of the little fishermen’s restaurants or up into the rocky hinterland for something a bit grander.

Where are the French?

But there’s something missing from this story – the French. It was the English who popularised the sun-soaked coast and created much of its infrastructure. In Nice, even today, one walks along the Promenade des Anglais, the long stretch of pathway along the waterfront constructed in the 19th century. And it was the tanned Americans who helped popularise the Côte d’Azur as a summer destination.

In 1936, the socialist Front Populaire introduced congés payés, paid holidays for the French workforce. On 31 July, every factory and workplace closed its doors for two weeks, and suddenly enormous numbers of French poured in by train to Nice and the Côte d’Azur. The Blue Train had already become more accessible to the middle and working classes with sleeping carriages for second and third class passengers added in the early 1930s. Quelle horreur! according to the bourgeosie.

In opening the way to the Red Trains, we close it to the famous Blue Train.

After the horrors of WWII and the occupation of the Riviera, the French began to claim the coast for themselves, starting with Brigitte Bardot. At the Cannes Festival in 1953, Roger Vadim, then a young film-maker and married to Bardot, recognized the opportunity for a starlet who could catch the press’s attention. Brigitte, in Paris, received a wire: “Take the Blue Train STOP Bring evening dresses.”

Three years later Vadim made the sexually charged film And God Created Woman, starring the young Brigitte Bardot, as a luscious fisherman’s wife who has a torrid affair with her husband’s brother. The film was shot entirely on location at Saint-Tropez, formerly a sleepy fishing village, but which soon became filled with jostling tourists seeking a glimpse of Bardot.

End of an era

While the Blue Train continued to run, it was facing competition. The 1950s saw the beginnings of the French motorway system, so that carloads of sweaty families could reach the southern coast. In the 1960s, Nice airport was handling a million passengers a year. The famous Blue Train would soon run only from Paris to Nice, as a new high speed train, the Flanders – Riviera, was implemented from Calais to San Remo. Gradually it lost its famous accoutrements; the bar was removed, and meals in the glamorous dining car took place only up to Dijon.

By 1978, the Blue Train and its promise of luxury had ended.

Now, billionaires, kings and queens, movie stars and celebrities still flock to the Côte d’Azur, where some of the most expensive real estate in the world can be found. But the era of the Calais – Méditerranée – Express, the Blue Train, cannot be recreated; its hedonistic and free-wheeling lifestyle belongs to another time in history.

Have you taken an amazing train journey? Tell me in the comments below.

Sources

Jim Ring, Riviera: The Rise and Rise of the Côte d’Azur, Faber and Faber, 2011

Lita-Rose Betcherman, The Riviera Set, Bev Editions, 2010

Anne de Courcy, Chanel’s Riviera, St Martin’s Press, 2019

Further reading

Imagine yourself in the dining car of the Blue Train at the sumptuously decorated Train Bleu restaurant at Paris’ most beautiful train station, Gare de Lyon.

Great article… Oh to be on the Blue Train right now! On my bucket list…

There’s talk in France of trying to bring it back… wouldn’t that be fabulous!

Great article Madame! I didn’t realise it was the Americans who frequented the Mediterranean before the French.

It’s amazing, isn’t it! Coco Chanel did a great job in encouraging the (wealthy) French to get their suntan in the south, but it took a long time.

I absolutely loved this article! I took a train in November 2019 from Paris to Amboise then from Amboise to Lourdes. I flew from Lourdes to Nice. Trains are so much more comfortable than airplanes. I wish the blue train was still in service. I long to go back as soon as this pandemic is over.

I’m so glad you loved the article! Wouldn’t it be wonderful to have the luxury of the blue train again, with cocktails, a fancy dinner and a good night’s sleep with the gentle rocking of the train.