In a country with thousands of beautiful châteaux, it’s easy to imagine that any could simply be lost to history. War, weather, revolutions and natural disasters have all taken their toll on the built landscape. But lost royal châteaux? To paraphrase the famous quote from Lady Bracknell: “To lose one château may be regarded as a misfortune; to lose more than one looks like carelessness’.

French monarchs, it seemed, were never satisfied when it came to their royal mansions. The glamorous Sun King, Louis XIV, could while away his time at no less than seven royal residences, yet still felt the need to create his glittering palace in Versailles as well as a retreat in Marly when life at court became too hectic. His grandson, Louis XV, also with lofty ambitions and obsessed with hunting, built not one but two châteaux, in Compiègne and in Saint-Hubert, purely for the purpose of resting after a long day in the saddle hunting game.

Today we can still visit many of the many palaces and châteaux which have harboured the French kings and queens over the past thousand years. Others have been razed to the ground, and only in our imagination can we glimpse the pomp and glamour of royal life. Here are six of the lost royal châteaux of France.

Louvre Palace

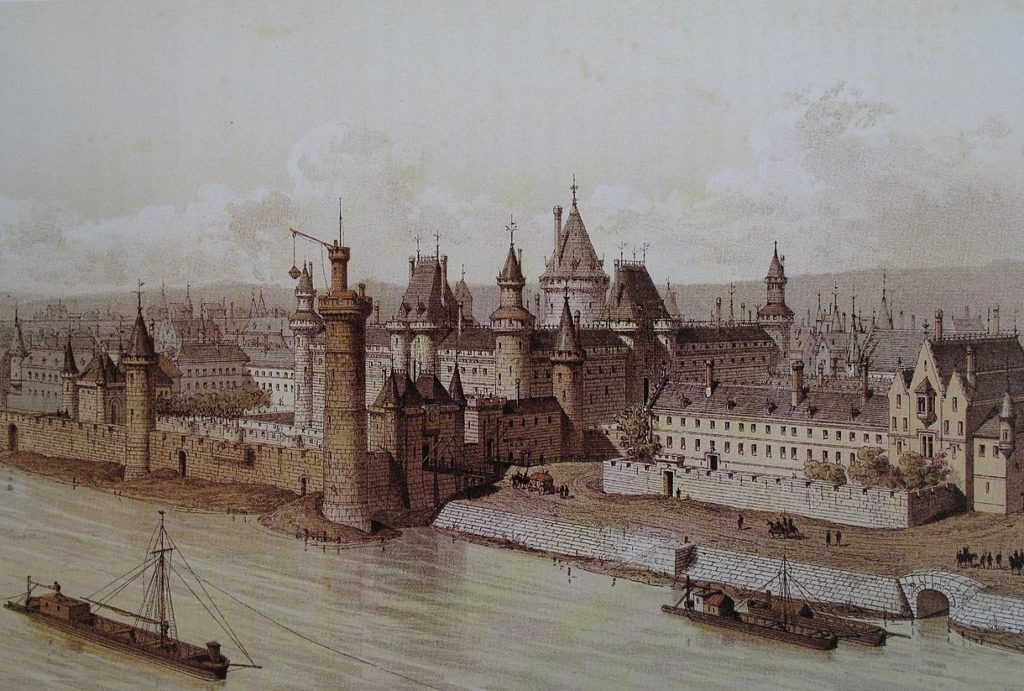

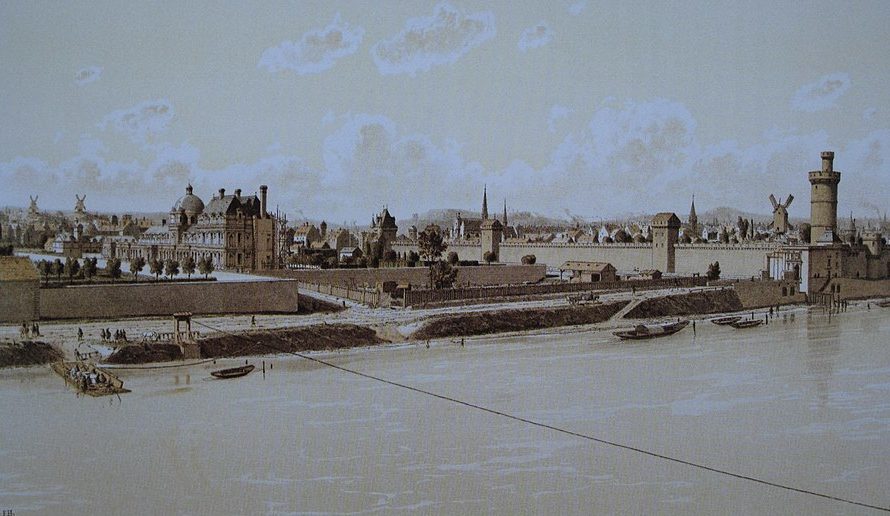

Would it surprise you to know that the most visited museum in the world, the elegant Louvre in Paris, was once a medieval fortress? The Paris of the 12th century was tiny, and surrounded by warring factions. Phillipe Auguste, the first to call himself ‘King of France’, ordered defensive walls to be constructed around Paris in 1190, and for further protection, a tall medieval fortress on the right bank of the Seine River. This castle stronghold, the Louvre, was protected with thick stone walls and a large water-filled moat. A great tower rose powerfully from the centre of the court, thirty metre high, and surrounded with deep ditch to keep invaders from scaling its walls. This ‘Grosse Tour du Louvre’ was designed to provoke fear in the neighbouring feudal lords, as well as act as a prison if they refused to pay their dues to the King.

Palais du Louvre under Phillipe Auguste

Louvre under Charles V, 1380

As Paris grew, so did the need for new defensive walls, so the original Louvre Palace found itself somewhat obsolete as a fortress. Charles V decided to use the Louvre as his official royal residence in 1364, and it became known as the ‘joli Louvre’ with its pretty turrets, chimneys and courtyard. With various wars and conflicts the Louvre was abandoned as a palace and was used mainly as a prison and for storing weapons. In 1528 the Great Tower was demolished and many of the original buildings were torn down not long afterwards. The Louvre we see today dates mostly to the 17th and 18th centuries, and only remnants of the lost royal château can be seen in the basement of the museum.

Château Lusignan

The lords of Lusignan originated in the Poitou region, in western France. Their fortified castle, the Château Lusignan was once one of the largest in France, though there is very little which remains today. The Lusignan family were not kings of France: Guy Lusignan became the King of Jerusalem in 1186. Unfortunately he was not terribly successful as king, and was captured and imprisoned by Saladin, the leader of the Muslim military campaign against the Crusades, merely a year later. As a result of political machinations he was appointed King of Cyprus, but ruled there only two years until his death in 1194. His heirs continued their reign over the small island state for several centuries.

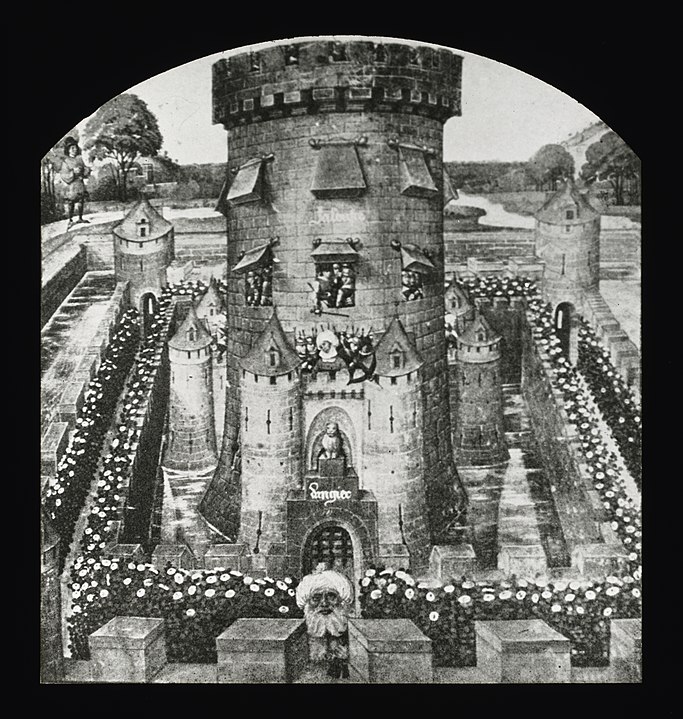

There is a local legend that the Château Lusignan was created by the fairy Melusina, who could take the form of a dragon. The castle dates to the mid-10th century, though was rebuilt several times up until the 14th century. It was the favourite residence of the Duc du Berry, who had it immortalised in his well-known Book of Hours Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry. But given the resistance of the lords of Lusignan to royal authority during the Wars of Religion, the castle was demolished by Henry III in 1575. The so-called tower of Melusina, over which we can see the dragon spirit flying in the Duc du Berry illustration, was torn down in 1622.

Château de Saint-Hubert

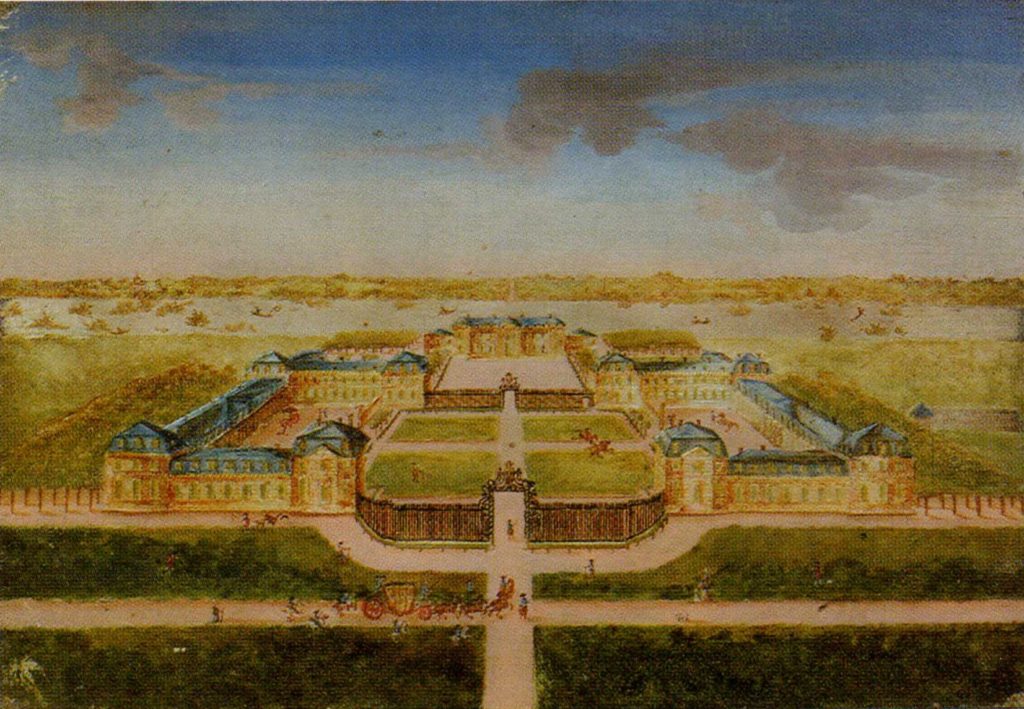

What does one do after a long day of hunting and there’s nowhere close by to feast on the day’s catch? Build another château, of course. The forest of Rambouillet, only around 30 kms from Versailles, has long been a favourite hunting spot for French kings. The Duc du Penthièvre, cousin to the King, lived in the small but lovely Château de Rambouillet, but had so far refused all requests from his cousin to purchase his house and grounds. And so plans were made for a ‘simple’ hunting lodge next to the nearby town of Le-Perray-en-Yvelines. Given that Saint Hubert is the patron saint of hunting, it was a perfect name.

Work commenced in 1755, but it was soon obvious to Louis XV that a full scale château was needed to house his mistress, Madame de Pompadour, and his many courtiers who complained vociferously at the lack of space for their lofty selves and their horses. Plans were revised and work on a grand mansion began anew. Marble statues lined the forest paths, the interiors were richly decorated with Gobelins tapestries, and the last mistress of Louis XV, Madame du Barry, planted a blossoming cherry grove. Unfortunately for the king, he was not to see the finished château of Saint-Hubert; he died in 1774, the year of its completion. His grandson, Louis XVI, had no interest in the grandest of hunting lodges, and managed to persuade the Duc du Penthièvre to sell him his beloved Château de Rambouillet instead. Subsequently, Saint-Hubert was abandoned. The château was demolished in 1855, and all that remains is a stone wall on the edge of the man-made pond, l’Etang St-Hubert.

Château de Saint-Cloud

If you wander through the grandiose gardens of Saint-Cloud today, there is a rather peculiar formation of yew trees. Follow the outline of these triangular trees and you will end up where you started, because the trees mark where the royal château of Saint-Cloud once stood. This marvellous château, with a breathtaking as well as strategic, view of Paris, dates back to the 16th century. It is infamous as the place where Henri III installed himself during the Wars of Religion to invade Paris, but was instead assassinated there in 1589 by a fervent friar.

The château itself didn’t actually become a royal residence until 1658, when the brother of Louis XIV, ‘Monsieur’, purchased the house and grounds. Monsieur, or the Duke of Orléans as was his official title, spent a fortune on expanding an already a rather large mansion. His Galerie d’Apollon was a masterpiece, its 45 metre length covered with art dedicated to the myths of Apollo, a richly decorated salon at each end. Louis XIV himself was supposedly filled with such envy that he immediately ordered a Galerie to be built in the palace of Versailles, now known as the Galerie des Glaces, or Hall of Mirrors. Marie Antoinette loved the château of Saint Cloud so much that her husband, Louis XVI, persuaded the Duke of Orléans to part with it, and it was bought for herself and her children in 1785. Sadly, she was not to spend much time here, courtesy of the French Revolution.

But it was not the chaos of the late 18th century which destroyed the château. Less than one century later, Napoléon Bonaparte had moved out and his nephew Napoléon III had moved in. It was here that Queen Victoria and Prince Albert stayed upon their visit to Paris in 1855. And it was here that Napoléon III declared war on the Prussians in 1870, and the château would be destroyed after it caught fire after fierce shelling from both sides. It was finally pulled down in 1891.

Hôtel des Tournelles

So-called due its many petites tournelles, or small towers, the Hôtel des Tournelles in Paris owed its existence to the English. Towards the end of the long Hundred Years War, in 1420, the English had pillaged their way along the Seine and had taken Paris. The Duke of Bedford settled himself in the Hôtel des Tournelles in the Marais district, next to the Bastille. At that time the palace was only a ‘small’ house, first built in 1390. When the Duke finally left 16 years later, he had expanded and embellished and even added a gallery with painted green courgettes on the walls. The royals liked what he’d done to the place so much that they moved themselves in.

This palace counted several courtyards, a number of chapels, twelve galleries, two parks and six large gardens, as well as a labyrinth known as the Daedalus, and a further garden or park of nine acres

Jean-Aymar Piganiol de La Force, Description de la ville de Paris et de ses environs, 1742

In the year 1393, a masquerade ball was given in this palace, at which Charles VI was disguised as a ‘savage’. The Duke of Orleans held a flambeau too near the king, set fire to his dress, and but for the presence of mind of the Duchess of Berry, he would have been burnt to death… four lords in waiting perished in endeavouring to extinguish the flames.

The History of Paris from the Earliest Period to the Present Day, 1825

Hôtel des Tournelles, 1550

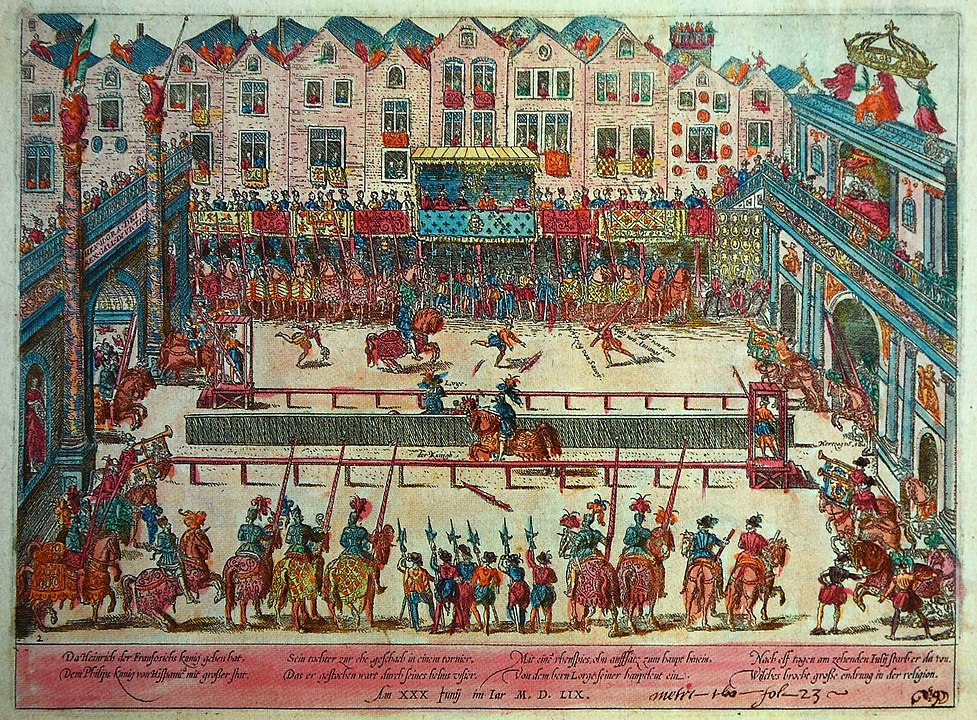

Henri II and the jousting tournament. Images WikiCommons

The Hôtel des Tournelles met its doom on a sunny day in June, 1559. Henri II was struck in the eye during a jousting tournament held at the palace, and died painfully from his wounds 10 days later. His queen, Catherine de Medici, who had long wanted to rid herself of the Hôtel and build elsewhere, ordered the house to be destroyed and the land sold. Much of the nobility rejoiced, for the palace was close to a sewer and apart from the strong and unpleasant odours, outbreaks of disease were common. There is no trace of the Tournelles remaining today, and in its place now is the elegant Place des Vosges.

Palais des Tuileries

The last of the lost royal châteaux is the only one to have been invaded and occupied more than once by angry mobs of Parisians. The ground on which stood the Tuileries Palace had a humble beginning, as the thick clay made it a perfect spot for making tiles or tuiles; hence the name tuileries. After the death of Henri II, Catherine de Medici chose the location to build herself a new palace in 1564, possibly looking for a little peace and quiet, as the grounds were actually outside the walls of Paris at the time. Under the next French kings the palais was expanded until it was eventually joined to the Louvre by the Grand Galerie along the Seine.

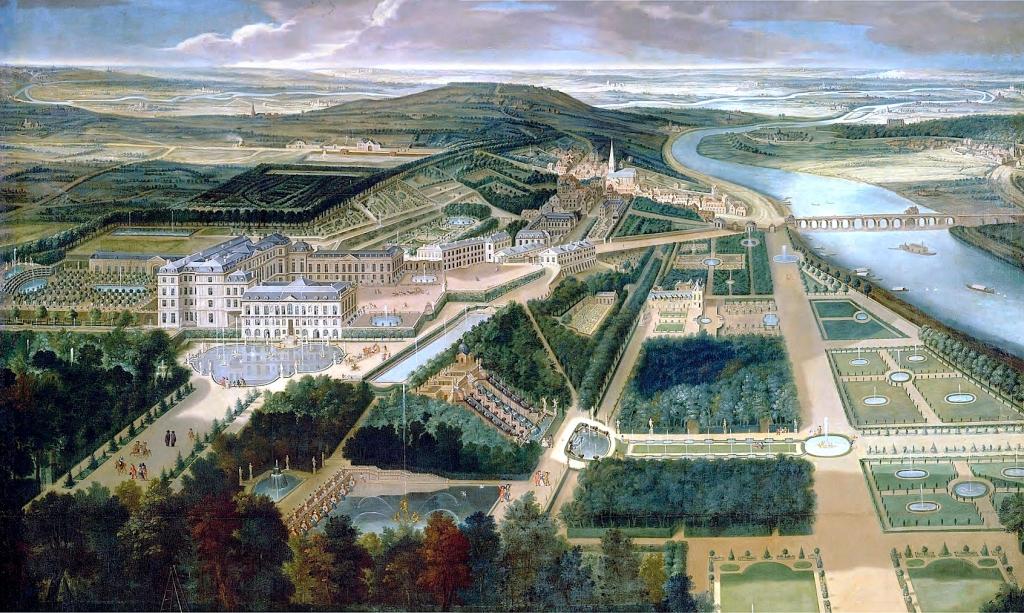

Tuileries Palace in 1585, outside the city walls

Tuileries Palace and Gardens, images from WikiCommons

In the 17th century, the sumptuous Tuileries Gardens were the pleasure grounds of the nobility, where Louis XIII kept his menagerie (and hunted the animals). Opened to the public of Paris in 1667, it became the place to be seen, a formal jardin à la française with wide avenues trimmed with chestnut trees, boxwood hedges and flower beds, and exquisite ornamental fountains.

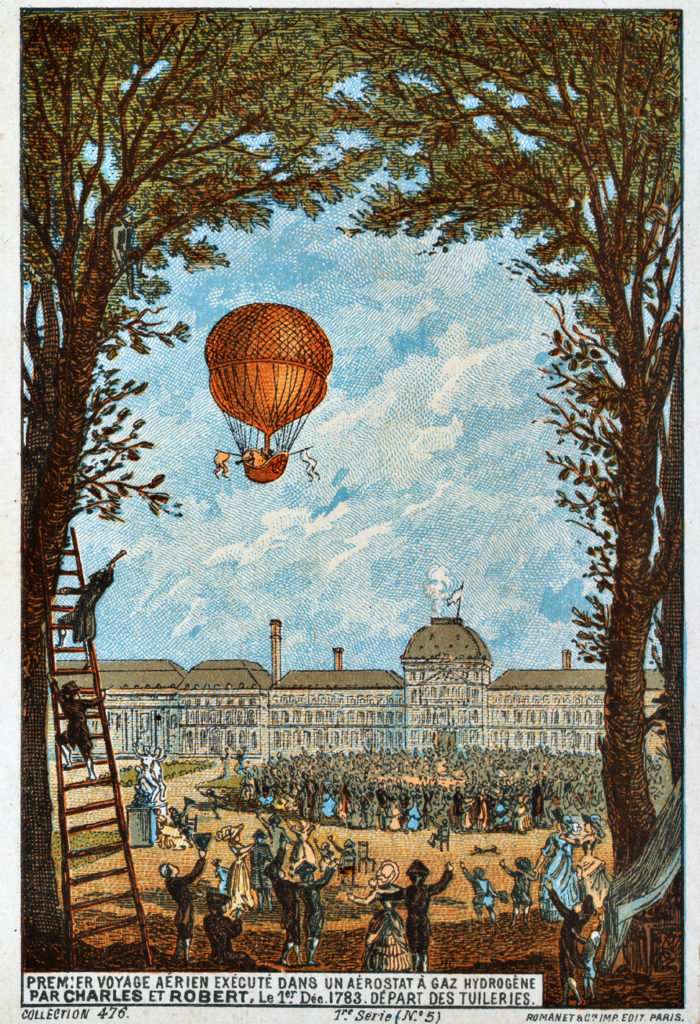

The palace and gardens were largely abandoned under Louis XIV when he moved his court to Versailles, and were only used for short periods when the royal family found themselves in Paris. And for the first manned hydrogen balloon flight, which rose to the skies in 1783. However, in October 1789, Louis XVI, Marie Antoinette and their children were forced to move to the Palais desTuileries when the women of Paris marched on Versailles and demanded action from their King. As the French Revolution progressed, life for the royal family held hostage in the Palace deteriorated. In June 1792 a large group of enraged sans culottes managed to gain access to the palace where they terrorized the king for several hours. Not long afterwards, on 10 August 1792, thousands of armed and angry revolutionaries stormed the Tuileries, compelling the king and his family to escape, and which directly led to the formation of a republic six weeks later.

Balloon flight, 1 December 1783

Tuileries Palace in ruins, 1871

The palace was again to play centre stage during the Revolutions of 1830 and 1848 when it was occupied by Parisians rebelling against the restoration of the monarchy. But it was in 1871 that the beautiful Palais desTuileries, symbol of the old, royal Paris, was finally destroyed, when it was deliberately set on fire during the bloody Paris Commune. Eleven years later it was completely demolished, and only the gardens remain today.

Have you stood on the site of long disappeared history?