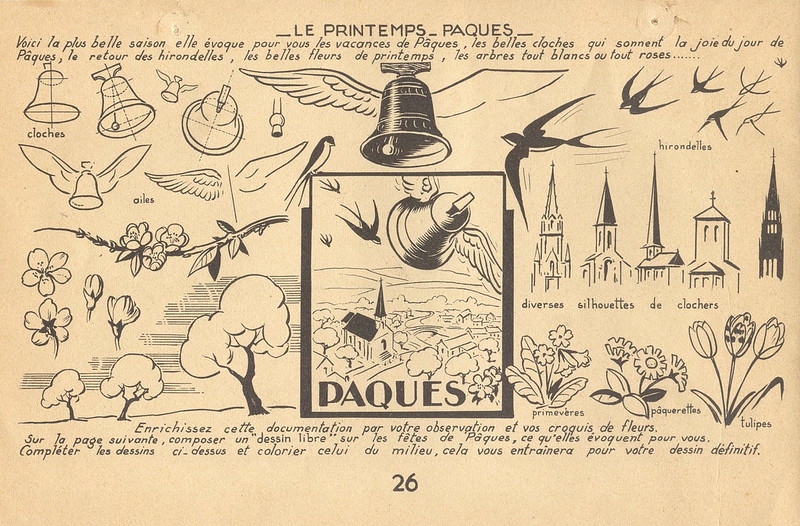

Easter, or Pâques in French, is a beautiful time of the year. The bright yellow flocks of daffodils dance in the sunlight, joyous after a long winter. The first of the pink blossoms twirl their way around branches sprinkled with tiny green shoots, alive with tiny birds flitting to and fro, creating a nest for their soon to be babies. In the markets, the first of the sweet, luscious strawberries appear. And chocolate! Sitting proudly on the counter of every pâtisserie, boulangerie and chocolaterie are intricately moulded, gorgeously wrapped chocolate eggs, chickens, bunnies and bells. But why are there Easter bells?

In French Easter tradition, the church bells stop ringing on the Thursday before Easter, Maundy Thursday. They sprout small wings and fly to Rome, taking with them all the collective grief at the death of Jesus, where they receive a heartfelt blessing by the Pope. After a short rest, les cloches de pâques flutter their way back to France, collecting chocolate eggs along the way. Early in the morning of Easter Sunday, the flying bells gently drop the precious chocolate into gardens all over France. And with much joy and delight, the children hunt in every corner, every nook, baskets in hand, for every last chocolate egg.

Have you ever wondered why we give eggs at Easter? In Christian tradition, eggs were forbidden to be eaten during the 40 days of Lent. Yet hens still lay, so when Easter arrived the basket of eggs in the kitchen was fairly full. In France, there’s an Easter omelette. The story goes that William of Aquitaine, hugely powerful in the south west of France the 9th century, habitually invited all his vassals (feudal tenants) to a meal on Easter Sunday made of eggs – l’omelette pascale. In the Middle Ages, on Easter Monday, the poor would walk from farm to farm where they would be given eggs or omelettes. There’s even a legend that Napoléon Bonaparte, whilst marching in the south of France, gave orders that all available eggs be used to make one enormous omelette for his soldiers at Easter.

{Related post: 8 Surprising Facts in the History of French Cooking}

But the tradition of a French Easter egg hunt belongs not in France, but in Germany. In the 16th century, the congregation of Martin Luther, leader of the Reformation, hid eggs in the garden for the women and children to find. Eggs were a symbol of the resurrection of Jesus, the empty shells a metaphor for the empty tomb found by the women in Jerusalem.

Over time, the eggs were coloured with natural dyes, and the legend of the Easter bunny was born (also in Germany). The bunny, also a symbol of fertility and new life, would lay these coloured eggs in nests left in the garden, to be collected by excited children on Sunday morning. And yes, we know that rabbits do not lay eggs – read this article about the legend which grew up around the Easter bunny.

When German immigrants settled in Pennsylvania in the 18th century they bought their stories of the Easter bunny with them, and the tradition spread. In England, Queen Victoria had lovely memories of hunting for eggs in the gardens of Kensington Palace, organised by her German born mother, and this helped to popularise Easter egg hunts in the United Kingdom. Even in France, there are stories of egg hunts in the palace of Versailles, where gold leaf was delicately painted onto hard boiled eggs for the royal children to seek.

Chocolate eggs were given at Easter several hundred years ago, but they were dark, and bitter, and only for the wealthy. It was in the UK, in 1905, that the chocolate company Cadbury produced milk chocolate eggs for the first time and voilà, the modern Easter was born.

But back to the flying bells. In France, church bells still toll through the day to mark the time. In the tiny village where my husband grew up, the house, a former boulangerie, sits directly across from the church whose bell rings three times daily. Thanks to the clanging bell I know when to wake up, when to prepare lunch, and when to unwind at the end of the day (seven in the morning, midday and seven in the evening). So over the Easter weekend, their stillness is overpowering.

Once les cloches volantes have delivered their sweet treats to the sticky-fingered children, they fly back to their rightful place in the church, and ring joyfully through Easter Sunday to celebrate the resurrection of Jesus. And all is well in France again.