Should you go looking for the prison cell in which Marie-Antoinette spent her last few months, it no longer exists. Imprisoned in the former medieval fortress of the Conciergerie on the Quai d’Horloge in the centre of Paris before her ‘trial’ and death, the dank and dark cell in which she rested, alone, unable even to kiss her children goodbye, was later turned into a memorial. The death of Marie-Antoinette by the sharp blade of the guillotine may have been quick, but her death sentence began well before.

First, the death of the dauphin

By the end of 1789, life for the royal family had changed beyond recognition. The Revolution was in full swing: the walls of the Bastille had been torn down in anger, and on 5 October, thousands of women determined to end the bread shortage had descended upon the Palace of Versailles to bring to Paris the “Baker, the Bakeress and the Baker’s boy”.

{Here is my post on the Women’s March on Versailles}

But more importantly, Marie-Antoinette found herself once again mourning the death of one of her children.

As the Estates General met for the first time since 1614 and formed a procession through the streets of Versailles, led by Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette, the sickly Dauphin Louis-Joseph waved from a balcony as his parents passed.

One month later, the seven and half year old had died. Both the king and queen were inconsolable, never mind that they were at the same time facing a crisis of government. Whilst all of France had rejoiced at his birth, it appeared to the royal family that no one at all cared that the heir to the throne had died. Marie-Antoinette later wrote to her brother:

‘At the death of my poor little Dauphin, the nation hardly seemed to notice.’

The nation’s hatred of Marie-Antoinette, known as ‘Madame Deficit’ for what was believed to be her extravagant spending, knew no bounds.

A gilded prison

Now settled fairly comfortably in the Tuileries Palace on the banks of the Seine, were the king and queen prisoners? The Revolution was still in its infancy, and there was still hope for a constitutional monarchy. Marie-Antoinette walked daily in the famed public gardens of the Tuileries with her children, hoping to win over the hostile Parisians with her style, grace and charm.

With a generous allowance from the National Assembly, the queen spent much of her time renovating the neglected and shabby palace, which had not been a royal residence since the days of Louis XIV. The numerous squatters in the royal apartments were ejected; as were the prostitutes who plied their trade in the area. Wagon loads of gilded furniture arrived from Versailles, and Marie-Antoinette was pleased to again have her favourite mechanical dressing table.

Designer Rose Bertin was a frequent visitor to the palace and set about creating gorgeous gowns with a revolutionary twist. Blue, white, red or pink gowns were popular at the time, and the queen made sure the fashionable and necessary tricolour ribbons were visible. Dinners, soirées, theatre, ballet; life appeared to go on as normal.

There was a silver lining, and it was that Marie-Antoinette now had time with her two remaining children. She had always adored being a mother, but the strict protocols of Versailles meant her children were usually in the company of governesses or tutors.

But the year was heartbreaking for Marie-Antoinette, with the death of her favourite brother, the Emperor Joseph II. He had been her ardent supporter and she held in her heart that he would somehow arrange for her rescue and release from Paris. He was succeeded by his younger brother, Leopold II, who was concerned for his sister but more afraid he would lose territory to Russia if he became involved in action against the revolutionaries in Paris. Leopold held the throne for only two years, and his son, Francis II, showed no interest in the welfare of his aunt. Marie-Antoinette could expect no help from her family.

Why did they not just escape?

Talk of escape was on the tip of everyone’s tongue as soon as the court arrived in Paris, and many plans were considered. Should the queen take the dauphin and flee to Italy, where the aunts and brother of Louis XVI were waiting? Should they travel in separate carriages, dressed as simple folk to thwart recognition?

In the end, their attempt to escape was a little too elaborate to be successful. They were to travel in an enormous and specially commissioned carriage fitted luxuriously with white velvet and with such conveniences as a small cooker, leather chamber pots and a hidden table, raised at mealtimes. The queen could not possibly travel without a selection of gorgeous new dresses, and most importantly, her nécessaire, a travelling dressing case made of glossy walnut wood, inside which held a silver teapot and chocolate pot and their spirit burner, and fifty other items such as desk accessories, glasses and bottles, cutlery, porcelain tableware, candlesticks, and a bed warmer. What the royal family needed was speed and camouflage; what they had was an overladen and heavy carriage and too many mishaps along the way.

The royal family were brought back to Paris, exhausted, humiliated, and now prisoners of the Revolution.

Life in the Tuileries was now bleak. Guards were at every door, at every gate (and had taken to ‘mooning’ the royal family at every opportunity). Letters were read, people were searched. The king fell into a depression, and was withdrawn and silent much of the time. The antics of his sister, Madame Élisabeth, who had been with the family since they left Versailles, was worrying as she was in constant contact with her brother, the comte d’Artois in Turin, who was hoping for an overthrow of the revolutionaries and a return to monarchy.

Marie-Antoinette, keeping up appearances of jollity for the suspicious public and for her children, was devastated. She wore her new green and purple dresses with pride, colours of the royalist cause as opposed to the tricolour of the revolutionaries.

Ironically, Marie-Antoinette now spent a large amount of her time in secret correspondence with officials of the National Assembly, discussing the best way to implement a constitutional monarchy. She had been accused of meddling in public affairs when she had not; now she was involved in discussions with the very people who had been her accusers.

Attack on the Tuileries

In 1792, new allies, the empires of Austria and Prussia, declared war on France. Furious at the toppling of the French monarchy, they also felt the confusion and chaos in Paris was a perfect time to extend their own borders. Their war cries caused immeasurable damage to Marie-Antoinette and Louis XVI.

Their aforesaid Majesties (the King of Prussia and Emperor of Austria) declare… on their word and honour as Emperor and King, that if the Tuileries Palace be insulted or invaded, that if the least injury, be inflicted on their Majesties the King, Queen and the Royal Family, and if measures are not at once taken for their safety, preservation and security, they, their Imperial and Royal Majesties, will wreak exemplary and unforgettable vengeance by yielding the town of Paris to military execution and utter subversion, and the guilty rebels to deserved death.

Manifesto of Duke of Brunswick, commander of the Austro-Prussian allied army, to the citizens of Paris.

The Duke of Brunswick obviously did not know anything about Parisians. Resentful, furious, and simmering with violence, this manifesto merely confirmed what they had believed all along; Marie-Antoinette was not on their side. Despite pretending to be full of patriotic pride, she and Louis XVI must be in cahoots with the enemy, Austria and Prussia. This was a call for action.

All through the sweltering night of 9 August, the tocsins rang throughout Paris, calling on everyone to arm themselves and strike before the foreigners invaded. By the early morning, there were thousands of angry Parisians, men and women, standing outside the wall, waiting for their opportunity to storm the Tuileries Palace. 900 fierce and loyal Swiss Guardsmen stood firm. But the armed and angry crowd was too much, and within a short time the palace had been invaded. The mob rampaged and pillaged, and seeking what they had come for – Marie-Antoinette and her husband.

For the king and queen it had been a dreadful night. Racked by indecision, as usual, Louis XVI had been convinced the palace would hold. Others were not at all certain, and so by eight o’clock, before the walls of the palace were breached, the royal family, including Princess de Lamballe, sought asylum in the nearby Assembly.

And so began the killings, which left the Tuileries a shambles of blood, corpses, severed limbs, broken furniture and bottles. People were hurled out of windows, killed in cellars, stables and attics, and even in the chapel where some had sought sanctuary, pleading vainly that they had not fired their guns. Rioters broke open the King’s wardrobe. Bloodstained hands were wiped on torn velvet mantles that once glittered with gold and the fleur-de-lys. The pike of an assailant, carried in triumph through the streets, was equally likely to be crowned with a fragment of Swiss uniform or a gobbet of human flesh. Many of those who tried to flee, whether Swiss or courtiers, were cut down by the mounted gendarmerie in the Place Louis XV. Paris became one huge abattoir, its gutters filled with the corpses of the Swiss, stripped naked and often mutilated. Traumatized wayfarers saw men kneeling in the streets and pleading for mercy before being beaten to death.

Antonia Fraser, The Journey of Marie Antoinette

Another palace, another prison

They had lost everything. With only the clothes on their back (the dauphin was also distraught at the loss of his puppy, called Citron), they were taken to the Temple palace, a former medieval castle, more recently used by dissolute nobles for their liaisons.

For a prison, it was not uncomfortable; but it was a prison, nonetheless. Marie-Antoinette finally had the simple family life she had always craved, and could keep herself busy with ordering new dresses to replace those lost in the carnage, but the relentless fear was paralysing.

The guards outside sang constantly a little ditty:

Madame goes up into her Tower

When will she come down again?

On 21 September, France was proclaimed a republic. Louis XVI was now plain old Louis Capet, and France had a king and queen no longer.

Things did not improve for the (former) royal family from here.

Farewells

Louis was taken from his family and placed in another room of the Temple. When he saw them 6 weeks later, it was to say goodbye forever. Hysterical, Marie-Antoinette, his children and his sister clung to him for several hours. He promised to return to them the following morning, but did not; Louis XVI was executed by the guillotine on 21 January 1793.

I entreat my wife to forgive me all the evils now inflicted upon her because of me, and whatever troubles I may have caused her throughout our marriage; as she may be absolutely certain that I secrete nothing against her, should she imagine anything with which to reproach myself

Last will and testament of Louis XVI

The next to go was young Louis Charles, no longer a dauphin or a king. A weeping and traumatised Marie Antoinette was forced to relinquish her 8 year old son to the officers who had entered her rooms without warning. Terrified and sobbing, he was taken away from his family and placed into the care of Simon, a former shoemaker entrusted with giving the boy a revolutionary education.

Marie Antoinette sank into a deep depression that neither her daughter nor sister-in-law could rouse her from.

A real prison

No longer sure whether she was living or dying, her turn came in August, when she was brought to the Conciergerie prison in the heart of Paris. Resigned to being in yet another prison, in her simple cell she placed the only items she now possessed – the watch she had received from her mother in Vienna, her wedding ring, a diamond ring and a locket containing her children’s hair. It was a far cry from the young bride who had arrived in Versailles and been overwhelmed with millions of livres worth of diamonds.

Even in a tiny jail cell she was not left in peace. Allowed to dress behind a screen, she was always watched by several guards. An enterprising prison officer saw his opportunity and, for a fee, allowed people to stand outside Marie-Antoinette’s cell and gawk at the spectacle inside. If they were expecting the haughty and imperious queen of old, dressed in finery and dripping with jewels, they were disappointed. At merely 37 years old, the former queen looked like an elderly woman.

Physically, she was deteriorating. She was too thin and her grey hair fell out in clumps. Even worse, over the previous months she had begun to haemorrhage significantly. This could have been from stress, fibroids, uterine cancer or early menopause – the cause is unknown. Her pain was constant.

The reckoning of marie-antoinette

When they came to take her away for her ‘trial’, she was in all likelihood relieved that it would soon all be over. Her trial consisted of two long days of outrageous lies and accusations hurled in her direction. Over forty witnesses offered ‘proof’ that she had sent money to her brother in Austria, that she had put the interests of Austria before those of France, that she had plundered the royal treasury for her fripperies and precious Petit Trianon. Every libellous pamphlet ever published was rehashed, and even the Affair of the Diamond Necklace made an appearance. In effect, she was accused of being the true power behind the throne and orchestrating to overthrow the entire French Republic (in her shoes, who wouldn’t?).

The worst was still to come.

A few weeks earlier, Louis Charles, as young boys do, had been caught touching his genitals. Always one to lie when caught out, he had told his caretaker that it was his mother and aunt who had lain with him and forced him to commit depravities. Even when confronted by his aunt Madame Élisabeth, he had obstinately stuck to his story.

And so with this ‘evidence’, it was put to Marie-Antoinette that she had committed acts of indecency with her own son. In the silent courtroom, she was asked what had she to reply to such an accusation:

If I did not reply, it is because nature refuses to answer such a charge against a mother… I appeal to every mother here.

The show trial having been completed, her fate was sealed. Death would be execution by guillotine later that morning, and there would be no last goodbyes with her family. These were her parting words, a letter to one of the few who remained loyal, her sister-in-law Madame Élisabeth:

The letter would never reach Madame Élisabeth, it was stolen by Robespierre and hidden under his mattress. As for Madame Élisabeth herself, she was executed on 10 May 1794.

the death of marie antoinette

Bleeding heavily, her undergarments soaked after the long trial, in her cell she changed into a white dress, ready to face the executioner. Still in mourning for her husband she was forbidden even to wear black. Had her accusers studied their history, they would have known that bereaved queens always wore white.

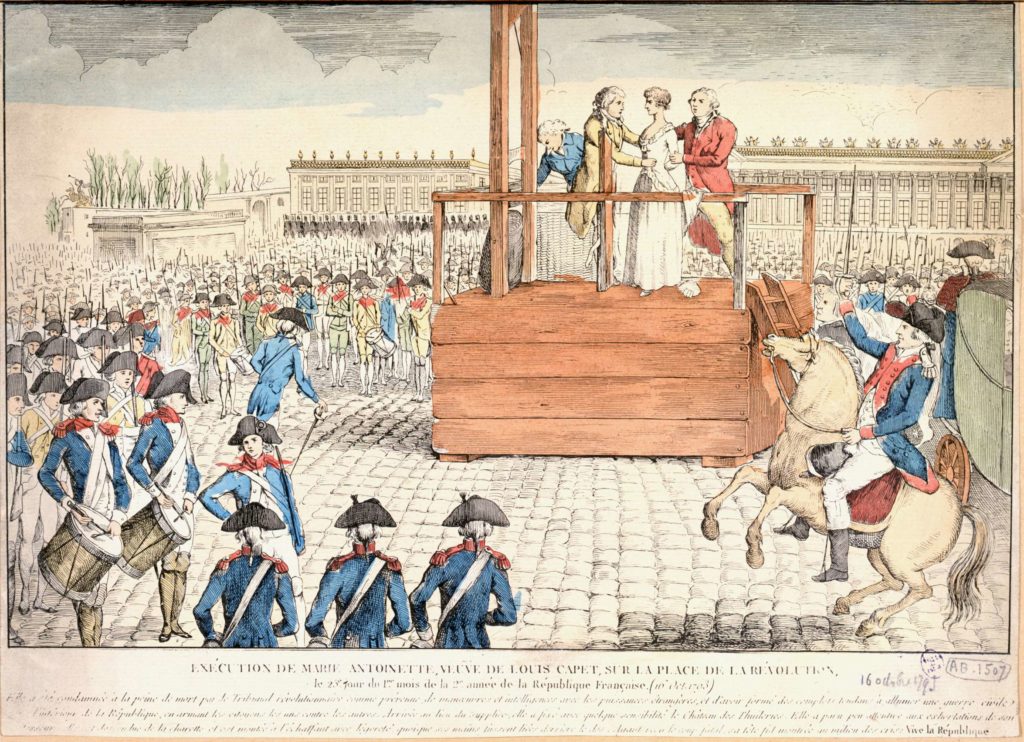

Her hair was shorn, her hands were tied behind her back. Whilst Louis XVI had at least been given the dignity of a closed carriage, Marie-Antoinette was placed into a tumbrel, an an open cart, for all of Paris to witness her humiliation. 30,000 national guards lined the streets in case of a last ditch attempt at rescue, and an artist sketched her figure as she passed under his balcony.

It was a long journey on a warm morning, the slow moving cart even stopping before a spiteful group of market women who screamed abuse for several minutes. Hundreds of thousands of spectators waited in Place de la Révolution for the Autrichienne to get what she deserved.

A priest who rode with in the cart told her: ‘This is the moment, Madame, to arm yourself with courage.’

‘Courage? The moment when my ills are going to end is not the moment when courage is going to fail me.’

If she were scared, it was well hidden. All witnesses stated that she carried herself with such grace there was no mistaking her for anything else but a queen. She mounted the scaffold, and was executed.

{Related post Last words on the Guillotine}

Granted no more dignity even in death, the body of the queen was dumped in a common grave with thousands of other victims of the French Revolution. Ironically, it was the same burial place for the hundreds who had died in the stampede caused by the fireworks on the occasion of her marriage in 1770.

In 1815, her remains and those of Louis XVI were taken to the Basilica of St Denis, the rightful place for French kings and queens.

Further reading

It’s been a long post, thanks for reading until the end!

Here are the links to the rest of my series on Marie-Antoinette:

What happened to Madame Royale, the daughter of Marie-Antoinette?

If you’d like to follow in her footsteps, this Pass Marie-Antoinette gives you special entry.

This is a fabulous online visit to many of Marie-Antoinette’s treasures