There are some French castles which breathe history, the past seeps into their weathered stones and whispers to you of wars and triumphs. Their high, centuries old towers stand tall, the walls keep constant watch and the green grass underfoot has never forgotten the spilled blood from invasions and treachery. But a castle fortress, a château fort, was often also a home, where noble marriages were joyfully celebrated and babies were born. The château de Clisson is one of these French castles – a patchwork of history and architecture from the twelfth to the nineteenth centuries .

a medieval fortress

Only 30km from the ancient town of Nantes, Clisson has always been strategically important, as it once marked the very edge of the wealthy and proud Duchy of Bretagne. Mentions of the town date back to the fifth century when a Roman garrison was constructed to keep out the marauding Bretons, and in 843 when the violent Norman vikings, not content with having sacked and pillaged Nantes, spread further into the countryside to do the same to Clisson. Having fixed and fortified the town, a treaty of 943 saw it included in the comte de Nantes, and therefore a part of Bretagne. By the twelfth century the town was in the hands of the powerful noble lords of Clisson.

The naturally high rock situated right next to the confluence of the Sèvre and the Moine rivers, was a perfect place for a fortress, and there had probably been a defensive structure there since the early 1100s. This French castle was taken by the English in 1206 but given back to the Clisson family a year later. In 1217 records from the Knights Templars noted that Olivier I de Clisson had added moats and ditches and greatly expanded on the château fort, as well as adding walls around the town of Clisson, making it a formidable defense against enemies. The castle welcomed Saint Louis, king of France, and his queen, Blanche de Castile, in 1230.

a lioness at the Castle

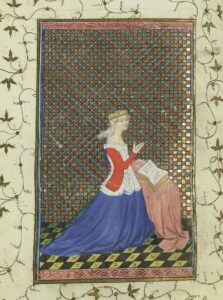

The French castle of Clisson was not strong enough, however, to withstand the rage of Duke John I Rufus over a territorial dispute with the Clisson lords, and it was demolished around 1240. The extent of the destruction is not known, though it is likely to have been rebuilt soon afterwards. The Clisson lords over the next century tried to stay loyal to both the French kingdom and the Duchy of Bretagne, but Olivier IV de Clisson was suspected of being an English spy and was beheaded in the market halls of Paris on August 2, 1343, for high treason on the orders of Philip VI of Valois. His wife, Jeanne de Belleville, and their young children, including the heir, Olivier V, then took refuge in England and their property, including the Clisson castle, was confiscated by the king.

Jeanne de Belleville was not one to accept her fate. According to local legend, she and her two young boys made a vow of revenge in front of their father’s decapitated head in Nantes. This determined noble woman then pitted herself against the French king and the Breton nobles who had killed her husband without adequte proof of his guilt, capturing French castles and fighting and pillaging along the Bretagne coast, earning herself the nickname “Lioness of Brittany”. She died in 1359 and several years later King Jean returned all the confiscated lands to Olivier V, who had been born in the château de Clisson, though it seems he spent little time at this French castle.

However, by the end of the next generation, the château de Clisson was no longer in the hands of this mighty family. Marguerite de Clisson, daughter of Olivier V and Countess of Penthièvre by marriage, made an ill-fated decision to kidnap the Duke of Brittany in 1420 in an attempt to have her own son in this coveted position. Defeated, she was stripped of her lands, including the castle in Clisson.

the end of the Château de Clisson?

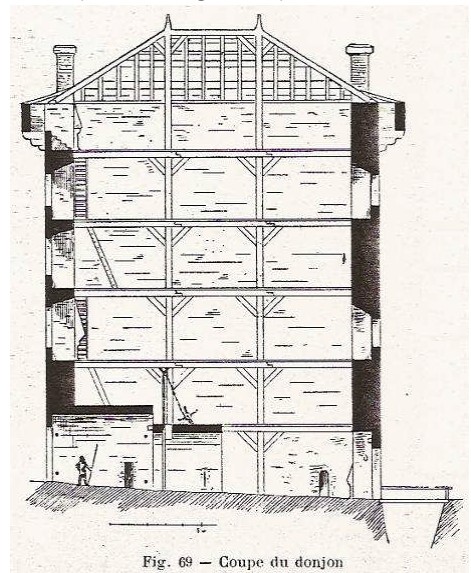

Now owned by the Dukes of Brittany, the château de Clisson undertook a major facelift and expansion in the mid 1400s. With the Wars of Religion in the following century, a Catholic Clisson was an important bastion of defense against the Protestants. In 1596, king Henri IV approved a large payment to lime merchants, stonemasons, sabliers and 100 day labourers for their work on the castle. Ramparts, bastions and a wide outer ditch were added at this time and large armies were stationed there until peace was established at the end of the century.

But a castle without a purpose, neglected and open to the elements, soon becomes a ruin. Half of the keep collapsed vertically around the middle of the 17th century; it is unknown whether this fall was the result of an earthquake or natural causes. The War in the Vendée, a counter-revolutionary and royalist attack during the French Revolution in 1793, saw Clisson and what was left of its fortress burnt and destroyed – the town’s inhabitants fled and did not return for several years.

Related post: The Château d’Alleuze

A happy Ending

But this French castle, so brave over the centuries as it withstood arrows, cannonballs and gunfire, and which never lost a siege, deserved a happy ending. Sculptor François-Frédéric Lemot saw so much potential in the ruined château that he went and purchased it in 1807, desiring to renovate and create an Italianate palace. Napoléon Bonaparte even visited Clisson in 1808 and expressed dismay at the castle’s ruined state. Luckily for us, Lemot restored very little of the château (his plans involved more change than preservation) and in 1962 it was bought by the Loire-Atlantique General Council. However, restoration as a Historical Monument had already begun in the 1920s, and over the last one hundred years the ruins have been saved from destruction.

When ruins tell us stories

This fortress with its thick walls and towers, overlooking the two rivers, was considered at the time a masterpiece of fortification. It valiantly withstood every attempted siege; cannonballs fell against walls 5 metres thick, and its irregular shape and hidden exits and underground passages made it impenetrable. A beacon was lit every night from the keep to guide travellers, and also used in times of war to give signals or direct troops.

Now, inside the polygonal enclosure we can see the remains of the large kitchens, a chapel, a spiral staricase, fortified gates, a paved courtyard and several towers. The Saint Louis Tower is the most distinctive, with its procession of deadly arrowslits. That the French castle was used as a residence is very clear, with the remains of fireplaces and window seats.

In the centre of the courtyard there sits a deep well. If stones could talk this well would have a thousand stories, central as it has been not only to battles but to daily life, the medieval equivalent to a water cooler. In later times it bore witness to the brutality men have inflicted; in 1794, 18 men from Clisson were killed and their bodies dumped inside this well by the revolutionary forces as France fought over liberty. They were exhumed in 1961.

the white sheep

An odd story was told in the early 19th century.

“One day,” the castle guardian said, “I thought I heard something at our door. I opened it and saw only a small white lamb crossing the courtyard. The dogs didn’t bark and let it pass. We don’t know who it belongs to, where it comes from; but it sometimes appears on beautiful summer nights. You see it on the walls, on the towers, in the moats: no one ever harms it; but you sense something at the sight of it.”

How to visit the Château de clisson

The castle is open every day except Tuesday, from February to December (closed January). It is also closed on the public holidays of 11 November, and 24, 25 and 31 December. The cost (as of 2025) is 6€ or 3€ reduced rate (if you are under 26, it is free). There is also the option of a guided visit.

The château website can be visited here.

Related post: A short but insolent history of the Château de Gaillard

Sources

Frédéric Lemot, Notice sur la ville et Château de Clisson, Paris, 1812

Paul Berthou, Clisson et son monuments, Nantes, 1910

Jocelyn Martineau, “Le château de Clisson”, Bulletin Monumental, tome 172, n°2, 2014. pp. 99-127

Unless stated otherwise, the photos in this article are the property of the author.