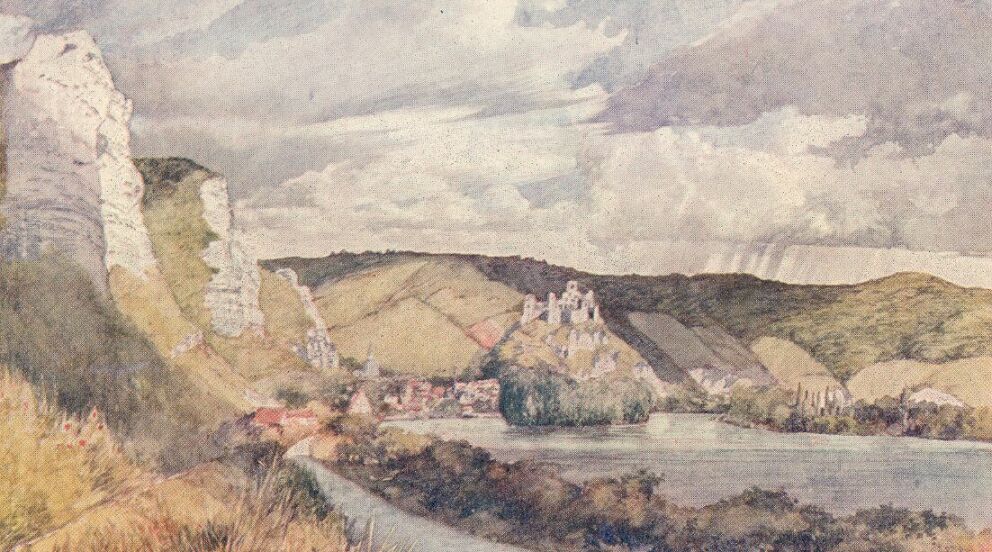

If you’ve ever visited the Château Gaillard, perched majestically atop a tower-like rock overlooking the Seine river in Normandy, you would understand the title of the article. Richard the Lionheart ordered the construction of the château and likely laid a few bricks himself in his rush to have it finished, and was so enamoured at its completion that he is recorded as declaring “C’est un château gaillard!” It’s an old word, gaillard, and not easy to translate, but the closest we can get in this context is “What an insolent castle!” Strong and arrogant, bold and offensive, much like the lionhearted king himself, the history of the Château Gaillard is mired in death, from medieval battles over territory to drawn-out sieges to inconvenient and adulterous queens.

The history of Normandy is like watching a game of tennis between the French and the English, with control of the region changing often between the two. Ruled by Norsemen or Normans, the descendants of the Viking king Rollo for 300 years, in 1204 the small but powerful French kingdom took back control of the region. And the castle upon the rock was a vital player in this particular conflict.

As well as being perfect for grazing cows to make camembert, the valley in which is found the château was once the grand avenue from the kingdom of France into Normandy. The old town of Andely sat a few kilometres from the Seine river and originated in a convent of nuns created in 511 by Saint Clotilde, the wife of Clovis, first king of France. Saint Clotilde was the first to conceive of a house of religious women, and supposedly performed one of her miracles here. Upon the discovery of a spring during the digging of the foundations of the convent, she literally turned the water into wine to quench the thirst of the labourers. On 2 June every year in the town the Feast of Saint-Clotilde is celebrated at the Fontaine Saint-Clotilde, where the water is believed to have healing powers.

Upon this rock I will build my Château

The Rock of Andeli, some 90 metres high and 180 metres long, rises sharply from its base alongside the Seine river, accessible only from the hills behind which are connected to the rock by a narrow strip of land. Its commanding views over the Seine and the surrounding countryside made it of strategic importance. The story goes that King Richard the Lionheart watched from this rock a conflict between the French and several thousand Welshmen in the valley. Richard was so furious when his forces were defeated that he took 3 prisoners and threw the wretches over the precipice and watched them tumble to their deaths far below. When he needed a stronger defensive system, he supposedly thought of this rock.

Richard I had lost ownership of most of his estates in the duchy of Normandy when he was held for ransom for two years beginning in 1192. They were lost to the French King Philip II, who had signed a deal with Richard’s brother John Lackland. On Richard’s release, hostilities to regain his lost properties began. A series of battles and skirmishes eventually led to a peace deal between the two kings but left Richard in serious need of some castles to defend his borders.

Knowing that the Valley of Andeli was an important stop on the transport route, and being the point where the French had been most likely to invade Normandy in the past, under the terms of the peace deal forged in 1195-6 it was forbidden to build any fortifications there. King Richard, being a savvy political player and not at all scared of war, knew that someone would eventually break the treaty and it may as well be him.

‘Andeli shall be fortified’.

Richard the Lionheart

The problem was that technically, the Manor of Andely did not belong to him – it was the property of the Archbishop of Rouen who resisted all efforts from Richard to cede his interests (it was by far his most profitable possession). A king has connections to the highest echelons of the Church, naturally, and sought to have things his own way behind the Archbishop’s back. Furious, the Archbishop of Rouen issued an interdict over all of the duchy of Normandy. This was serious – there could be no church services, no confessions, no burials, no baptisms, no marriages. An English chronicler recorded there were “unburied bodies of the dead lying in the streets and squares of the cities of Normandy”. The Archbishop eventually relented when offered a number of more prosperous lands.

Richard, however, had already begun to build his château. Historians of the time recorded that thunderbolts of the church, threats from heaven would not stop the English king from defending his land: “He did not give up his business for this. He liked it so much, if I am not mistaken, that if an angel from heaven himself had come to urge him to abandon it, he would have blasphemed against him”.

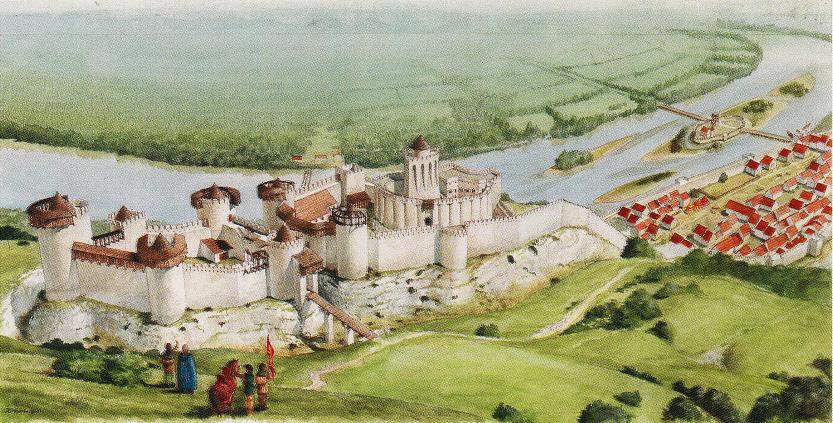

On a small island in the Seine, opposite the town, Richard began with a small octagonal fort flanked by towers which he joined to either side of the river with a wooden bridge. The town of Petit Andely was created, surrounded by a vast enclosure and soon populated, so with the château high on the rock it was a very well protected and fortified area. It was also completed in record time – a mere two years, from 1196-8. Richard oversaw every aspect of the building of this momentous and insolent fortress. The stone walls, striped in Roman fashion were thick and solid and the ditches were dug deep and wide into the rock. Large windows in the apartments and the keep provided magnificent views over the precipitous cliff to the Seine.

The castle was built in three main sections or baileys, with each section higher than the previous one and surrounded by its powerful walls with towers. With its drawbridges and steeply roofed towers it may have resembled a romantic castle, but the imposing and impressive central donjon tower which raised its walls on the loftiest pinnacle of the rock gave away its true function as a citadel.

“Qu’elle est belle ma fille d’un an” (How beautiful is my one year old daughter).

Exclaimed by Richard the Lionheart when he saw the completed Château Gaillard

The English king had complete faith in the indestructibility of his castle; that it would hold against attackers “as though its walls were made of butter”. He died in 1199, before his theory could be tested, which it was several years later, and the history of the Château Gaillard would take an about-turn.

If only these walls WERE made of butter

In September 1204, Philip IV decided it was time to take Andelys from Richard’s successor, his brother King John. When eager French soldiers were seen clambering over a line of boats which stretched from one side to the other of the Seine, the terrified Normans in the village of Petit Andelys ran up the hill to seek refuge in the castle. The fortress was designed to withstand a long siege, and its cellars were well stocked with French wines and English cheeses for the 300 garrisoned soldiers. But it had not counted on the additional 1500 villagers. An attempt to resupply the castle using armed ships to sail upriver had failed. But Philippe was more than happy to wait, knowing that hunger is the most powerful of all siege weapons.

By November the situation in the château had become dire, and several hundred villagers were released and welcomed by the French soldiers. Another few hundred met the same fate, happily accepting the food offered by the opposition. However, Phillipe, who was away at the time and wanted to see the siege prolonged, ordered that no Normans were to cross the French lines. So when the last group of villagers were freed from the castle’s walls, 500-1000 of them, they were greeted not with food and drink but with a shower of arrows. The terrified men, women and children found themselves in a no-man’s land where they were beaten back from both sides. For three months, in the depths of a cold winter, they were forced to live on the hillside and in the ditches surrounding the besieged château eating scraps of food, grass, dead dogs and eventually each other. Most died of starvation and exposure.

The siege ended after several French soldiers shimmied their way inside through a slimy toilet drain, made a racket to distract the Norman troops and eventually Philippe could force his way in. It had been five long months, and a tragic story in the history of Château Gaillard. The castle, believed to be impenetrable, now belonged to the French kingdom.

Scandal in the Castle

In 1314, three princesses were accused of adultery. Margaret of Burgundy and two sisters, Blanche and Joan of Burgundy were aristocratic women who had joined the French royal family through marriage, being wed to the sons of Philippe IV. By all accounts King Philippe, despite being known as ‘Le Bel’ for his handsome face, was not a merry king and his sons were not much fun either. The three women were accused of cavorting with two Norman knights in theTour de Nesle, a now disappeared tower on the Seine river that was once part of the defensive walls surrounding Paris.

Whether there was any truth to the matter or not, even a whiff of scandal could place the monarchy in jeopardy. Margaret and Blanche were very quickly found guilty before the Parlement of Paris, had their heads shaved as a humiliation, and were sent from Paris along the Seine to the Château Gaillard as punishment. Its condition at this time is not known, although it would certainly have been habitable as Normandy was still a disputed region between France and England and the importance of the château had not diminished. It’s unlikely they were shackled and held underground, but life in the tower could not have been pleasant. A historian of the time reported that they lived in “narrow seclusion, deprived of all human consolation, they ended their lives in misfortune and misery”.

Margaret was the wife of the heir to the throne and within a few months of her imprisonment, on the death of Philippe IV, she became Queen of France. But Louis X, known as ‘Le Hutin’ or ‘The Quarrelsome’ was as hard-hearted as his father and refused to forgive or release Margaret. She died (conveniently for Louis, as he married again five days later) within a year, with some contemporary reports claiming she had been strangled to death with her own hair in the tower of the castle.

Which left Blanche on her own in the cold, drafty fortress surrounded only by the memories of the dead, although defamatory rumours persisted that she “continued her adulteries” in her tower (no evidence exists to support this). Eight years after entering the donjon, in 1322, she found herself Queen of France when her estranged husband Charles IV (also known as ‘Le Bel’ or “the Fair”) became king. Charles refused to give Blanche her freedom and she remained at the Château Gaillard for several more years. She was visited in her tower in 1322 by the Bishop of Paris as Charles was seeking an annulment of their marriage, and the Bishop reported that she was happy and laughing and expressed no desire to leave her prison. After Charles remarried Blanche was sent to a nearby château where she died sometime before 1326.

Luckily for Joan, Countess of Burgundy, her husband Philippe V ‘the Tall’ was supposedly deeply in love with his wife and supported her claims of innocence in the Nesle Tower Affair. She ruled as Queen Consort until Philippe’s death in 1322.

The two knights who were supposedly caught in flagrante delicto with the royal princesses, Gautier and Philip of Aunay, endured a rather painful and horrible end. They were skinned alive in a public square, their genitals chopped off and thrown to the dogs, then beheaded and their bodies dragged through the streets behind a wagon to the common gallows where they were suspended by their shoulders and arms and left until they rotted.

The Nesle Tower Affair was instigated by Isabella of France, the daughter of Philippe IV who was Queen of England in 1308 – 1327. It is possible she made the allegations of adultery against the women in order to destabilise the French monarchy and create an opportunity for one of her children to inherit the throne. Her actions, however, inadvertently led to the imposition of Salic Law and the impossibility of a woman sitting on the French throne. Read my article here on why there has never been a French Queen.

Just a little bit more history

Thankfully, there are no more (recorded) horrors to recount in the history of the Château Gaillard. In 1334 the King of Scotland, a 10 year old David II was in exile in France and was given the château as a residence. A chronicler recounts “David de Brus, son of Robert de Brus of Scotland, a young man of about thirteen years, and his wife, sister of the king of England, were led secretly to France by some of their partisans in order to be withdrawn from the prosecutions of their adversaries”. David Bruce and his wife remained safely ensconced at the castle until 1341.

It is known that the Château Gaillard was in French hands in 1403 as Charles VI ‘the Mad’ gave his wife Isabeau of Bavaria “all the lands, rents, incomes and belongings of Andely”. But over the course of the Hundred Years’ War between France and England the castle changed sides numerous times (including another siege in 1419). When it was captured by the French in 1430, they were quite surprised to find there Arnaud Guillaume, Lord of Barbazan who was a comrade in arms of Joan of Arc and had been captured by the English and held prisoner. It was finally and determinedly taken by the French in 1449.

Neglected for 150 years, when Henry IV became king in 1600 he decided the château was too tempting for any ambitious Norman lord and so he ordered its destruction. Perhaps he also wanted revenge on the castle as his own father had suffered an arrow wound in a battle in Rouen and died at the foot of the castle in 1562. Letters patent from his son, Louis XIII gave orders that the original convent in Grand Andely founded by Clotilde could take what they could from what was left of the castle:

[their convent]…is in imminent danger of falling, where there is only almost no cover and the walls are mostly knocked down. We have given them and are making a donation of all that may remain of the demolitions of all the said Château-Gaillard, . . . either stones, beams and any wood, tiles, and any general things whatsoever that may be in it or above ground, except the donjon, which we want to remain in its entirety, as it has been abandoned.

By 1616 the Château Gaillard was in the state of ruin which we can see today. Only vestiges remain of the stone walls, the servants’ hall, the kitchens, the buttery, the chapel, the wells, the smithy, the armory, the stables, all the courtyard buildings necessary to maintain a castle life.

The two Andely towns became one, now known as Les Andelys, and the château became a much visited tourist destination. In 1828 the Duchess of Angoulême Marie-Thérèse-Charlotte, the only surviving child of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette, was travelling past Les Andelys and decided to make a stop. There was an old staircase which had to be climbed to visit the tower, and the story was told that she ordered a hole to be blown into the wall so that she didn’t have to use the stairs and show her underwear.

The history of the Château Gaillard has one more story to tell. In 1842 a traveller wrote about an underground chamber, or crypt, dug into the rock called the Hermit’s Cave. Townspeople told of an old woman called only Mother Gaillard, who lived in this grotto as an anchorite, a recluse. It was believed she had been there since the destruction of the castle, and that she would stay as long as any part of the castle walls remained standing. May she rest there forever, as insolent as the château itself.

Would you like to visit the châteaux of Rouen? Take a tour here.

Further reading

One of the first French aéronauts and the first to cross the English Channel by hot air balloon was Jean-Pierre Blanchard, who was born in Petit-Andely in 1747. You can read my article here about his amazing wife and aéronaute, Sophie Armand, who learnt the art of ballooning from her husband and became known for her daring exploits high in the sky.