At 38 years old, Julie d’Angennes was ‘on the shelf’ according to the ruthless aristocratic standards of 17th century Paris. She was not a great beauty, but she had been captivating hearts for much of her privileged life and one of the greatest questions of the day, even as she teetered on the edge of spinsterhood, was as such: Who would capture the heart of ‘Princess Julie’?

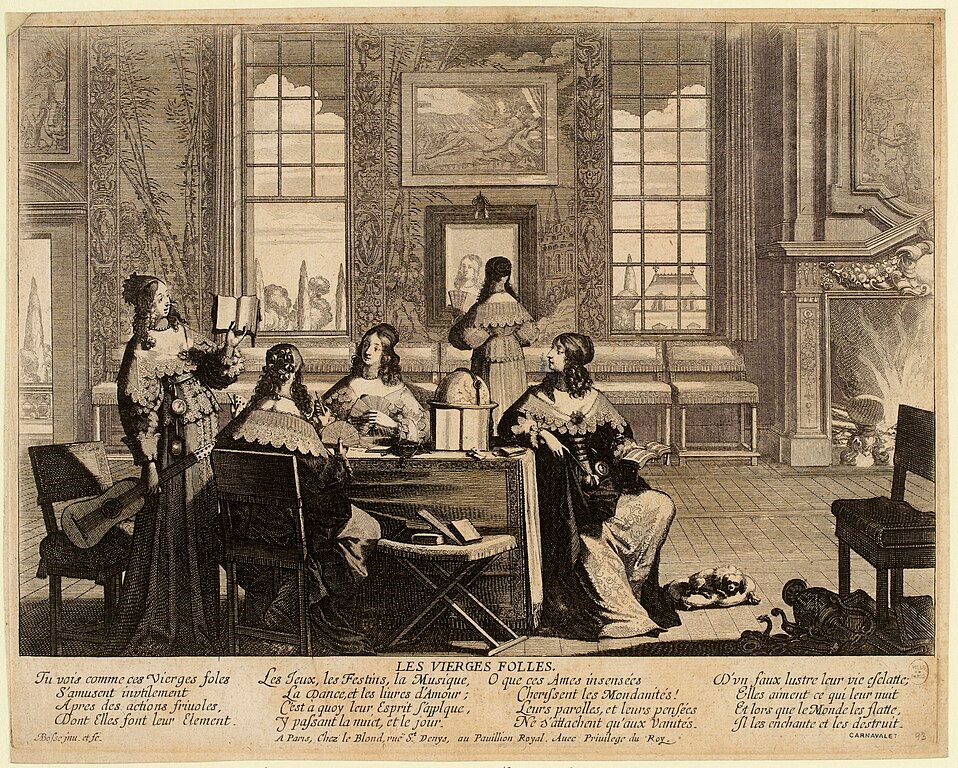

Born in 1607, Julie’s mother was Catherine de Vivonne, marquise de Rambouillet, whose luxurious house on Rue Saint-Thomas du Louvre was the heart and soul of 17th century Parisian society; anyone who was anyone was hosted at her famous literary salon and chambre bleu at the Hôtel de Rambouillet. Most often gowned in a chic red velvet dress, Julie was as much the centre of the elegant blue room as her mother. Intelligent, lively, funny and good-natured, by the age of sixteen (a perfectly marriageable age for the time) her suitors were writing poetry in her name and soliciting her hand. It was the height of fashion to be one of her admirers. But to be married? ‘No’ was her answer, time and time again.

After Hélène, there has hardly been a person whose beauty has been more generally praised; however she has never been a beauty. It is said that in her youth she was not thin, and that she had a beautiful complexion. Dancing admirably as she did, with the spirit and the grace that she always had, she was a wonderful person.

Gédéon Tallemant des Réaux, notorious 17th century Paris gossip, describing Julie d’Angennes

Who would eventually win her hand in marriage? Would it be the pithy poet Vincent Voiture, a frequent visitor to the Hôtel de Rambouillet and great friend of her mother’s? Or Antoine Godeau, wealthy and well-connected and very much in love with Julie but with a short stature which earned him the nickname nain (dwarf) de Julie. Perhaps the tall and handsome Hector Montausier, who impressed all the ladies with his exploits on the battlefield (and the bedroom). If it were completely up to Julie d’Angennes it would be Gustavus Adolphus, king of Sweden, whom she admired so much that, like a modern teenager with posters of boy-bands, his portrait took pride of place on her bedroom wall.

The Marquise de Rambouillet, her mother, had been married at the very young age of eleven. While she and her husband seemed to have made a love match, she was determined that her daughters should not have to suffer the same fate. She once told Tallemant de Reaux that if she had been left until she was twenty and not been obligated to marry, she would have remained unwed. In fact, of her five daughters, only two would marry; the remaining three entered convents.

Related post: The ten most beautiful cathedrals in France

It’s no wonder then, that Julie’s aversion to marriage was well known in the close-knit society of 17th century Paris. Unusually for the time she even had her own apartment within the large house, where she could receive close friends and entertain as she pleased. She once declared, in a burst of laughter:

“she did not understand why, in cold blood, a woman would take a master, and that husbands would always be the master, whatever they might say. She would keep her freedom as late as she could…”

Gédéon Tallemant des Réaux, Historiettes

When Julie d’Angennes met Charles de Saint-Maure Montausier, it was 1631 and she was 24. The average age of marriage for aristocratic women was 22, so she was already considered to be a little past her prime. According to Charles, his first meeting with Julie on a wintry day was a coup de foudre, love at first sight, according to his daughter, the Duchess of Uzés. The Marquise de Rambouillet and Julie were staying at an estate in Charenton, as Paris was infested with plague (actually the youngest son had just died in this particular outbreak) and Montausier, not yet known to the Hôtel de Rambouillet set, was determined to make their acquaintance and express his sorrow at their loss. Upon arriving, he and his friend were received by the elegant and eloquent Marquise herself:

The Marquise… received him with such natural civility and politeness. One never left her without admiration for her courtesy and gentilesse.

As they left, driving sedately through the Bois de Vincennes, Julie’s carriage was spotted. Montausier was seized with an unprecedented “feverishness”. His friend, who was acquainted with Julie, halted the young woman’s carriage and as required by society, the pair were introduced. The moment he saw Julie, Montausier said he was struck by a bolt of lightning, dazzling emotion, the memory of which was to pursue him until his death. According to his daughter, years later, he still wondered openly about this event, this sudden passion which was to upset the course of his existence.

We will never know if Julie felt the same, although there must have been enough attraction on her part to want to continue their conversation under the dry branches and winter foliage. Within a short time he was a regular visitor to the Hôtel de Rambouillet, but Julie was unmoved by his protestations of love, still having no intention to lose herself to a master.

It didn’t help Montausier’s cause that his elder brother, the dashing Hector, a frequent caller to the chambre bleu, was rumoured to have caught Julie’s eye. Everyone believed that if she was going to marry, it would be Hector. But tragically, Hector died in 1635 on the battlefield, leaving his brother the title and the hope that Julie may one day love him.

But Charles, the newly-titled Baron de Montausier (later it would be upgraded to Duke) was not an easy person to love. In fact, his nickname was ‘fagot des orties’, or bundle of nettles, for his somewhat prickly and forthright nature. He preferred reading to hunting; Julie loved parties and balls and dancing. But would opposites attract?

A 17th century ‘Recueil de devises’ in which high society figures were asked to create their own symbols/heraldic devices for a book, is telling in the differences between Julie and Charles.

In Julie’s emblem the white clouds gently swirl across a bright blue sky, a house sits far in the distance of this bucolic pastoral scene, and, oddly enough, a bear with a star for an eye meanders along a cloud. Below are the words Immota, or Unchanging. This was a woman who was perfectly content with her life.

Montausier preferred a little more action: his chosen emblem was an erupting volcano, with fire and lava spurting ruthlessly from its crater, perhaps a rather crude depiction of his passion. Four cherubic heads surround the fiery mountain, either to fan or extinguish the flames. His motto was Dant vires qui extinguere tentât, those who want to put out the flames merely give it strength.

For thirteen long years Montausier battled to win Julie’s heart. He wrote poems and sonnets, made anguished declarations of love, and endured mockery by the sharp-witted regulars of the Rambouillet set. Surrounded by her many friends and admirers, Julie continued to deny him. (Perhaps she found his liking for her maid, Pelloquin, with whom he fathered four children, to be a little bit of a red flag). Obviously, a grand gesture was needed.

The bristly yet brave Montuasier had fought on the battlefields in Italy, where he would have heard about a collection of tender madrigals given to countess Angela Bianca Beccaria, forty years earlier, called Chirlanda or Garland. The association between love and gallantry and flower garlands is very old. In ancient Greece, in Rome, floral wreaths adorned the doors of a beautiful women, placed there by hopeful lovers. At the dawn of the 17th century, the custom remained strong, on holidays, for gallants to offer their love a coronet of flowers, a floral diadem, a scented headpiece.

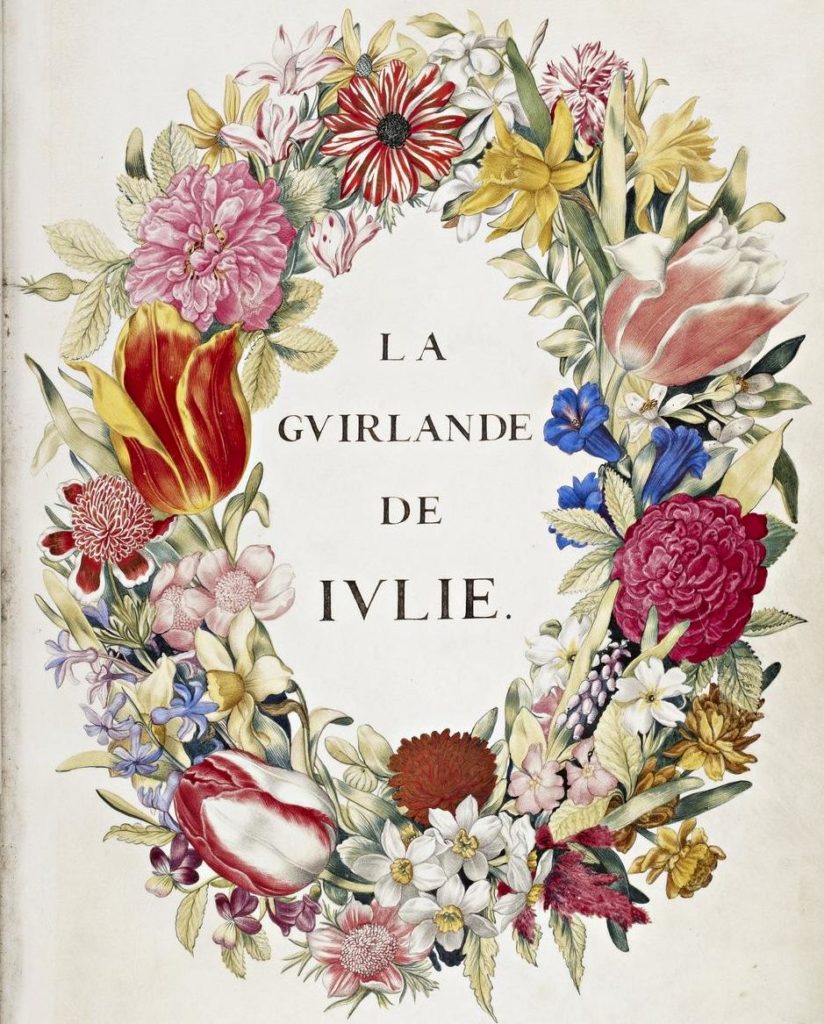

Montausier wanted to offer the literary equivalent of a floral garland; a collection of madrigals, all written in praise of the ‘incomparable’ Julie, as she was known. The madrigal was an Italian creation, a poem meant to be sung, which had not yet found its way into the French literature of the 17th century. The Hôtel de Rambouillet was full to the brim with poets, every man and woman who aspired to write had to be seen at the literary salon of the Marquise, so it was a perfect place for Montausier to find willing participants for his scheme. Deadlines were set, reminders were sent, every writer was hounded and harassed until at last, after two years, the book was ready.

Receive, o nymph adorable,

Zéphir à Julie, the first madrigal in La Guirlande, dedicated to Julie

whose hearts receive the laws,

this crown more enduring

than those which lay on the heads of kings;

The flowers composed here by my hand

can only imitate the golden blossoms of the heavens,

the water with which Permesse imbues them

gives them an everlasting freshness,

and every day my own beautiful flora,

which loves me and which I adore,

reproaches me with resentment

that my sighs, never for them,

have revealed this exquisite flower

that I have created for you. M. le M de Montausier

There were 61 madrigals, printed on the purest vellum (the skin of a pure white, stillborn calf), handwritten by Nicolas Jarry, the most superior master calligrapher of the time. Nicolas Robert, who would later become official painter of miniatures to Louis XIV, was commissioned to paint the flowers to accompany the text.

The exquisitely handcrafted pages were then bound in the finest red Morocco leather and nestled inside a book jacket scented with frangipane.

On the eve of Saint Julie, 22 May 1641, the fragrant La Guirlande de Julie was carefully and lovingly placed on her dressing table, where it would be discovered the following day.

Tallemant, writing 20 years later, called it ‘one of the most illustrious gallantries that have ever been performed.’

Sixteen of the poems flowed directly from the heart of Montausier onto the page. The remaining works were from nineteen others; some were writers such as Georges Scudery, others were admirers such as the aforementioned Bishop de Godeau. Even Julie’s father, the Marquis de Rambouillet, penned a madrigal for his daughter.

It was, in effect, to be a perfect book, to glorify the perfect woman. Julie’s perfections were even more than perfect; according to the Guirlande, she was more beautiful than every flower on earth.

Five of the madrigals were dedicated to roses, three to the imperial crown (fritillaria), and four to the narcissus or daffodil. At the very heart of the book, there are eight poems devoted to the lily, personifying Julie’s pure and white complexion, the essence of her beauty. Other flowers were chosen for their symbolic value, such as angelicas, carnations, jasmine, anemones, tulips, marigolds, saffron, hyacinths, irises and sunflowers.

Flower paintings were all the vogue in 17th century Paris, as maritime and overland exploration and trade with the east bought new botanical discoveries to Europe.

Related post: The botanical art of Madeleine Françoise Basseporte

Give me your colours, tulips and anemones,

Madrigal, L’Immortelle-Blanche (Everlasting)

carnations, roses, jasmine, give me your scents,

contrary seasons give out neither cold nor heat,

respect only wreaths

made of my flowers.

Don’t boast of being charming or pretty,

we can’t call beautiful what time erases,

to crown eternal beauties,

and to make their eyes joyful,

you must not be mortal.

If you seek freedom from the death

of your brilliant, but frail charms,

allow me to embellish them;

and if I offer them my eternity,

I’ll render them like Julie’s supple charms,

worthy to adorn her divine beauty. M.C

We shall never know Julie’s immediate reaction to her Guirlande, but it certainly set tongues wagging all over 17th century Paris, and no doubt inspired some suitors to up their game when it came to courting. Unfortunately for Montausier, Julie d’Angennes may have loved the book but did not fall lovingly into his arms. She remained unwavering in her commitment to singledom.

Montausier was soon sent back to the front in Germany, but unluckily was taken prisoner. An exchange of letters, poems and verses, full of love and emotion, mostly on the part of the broken-hearted Montausier, was soon underway between the two. However, he secured his own release (and that of his fellow soldiers) with family funds and after 10 months he returned to Paris, at the beginning of 1645.

It had been thirteen years since Julie d’Angennes and Charles Montausier met on the outskirts of Paris. Julie was now 38, and societal pressure was forcing her to re-evaluate her decision. Even the queen dowager of France, Anne of Austria, took Julie aside to ask her personally to put Montausier out of his misery. However, it was only after a frank discussion with her own mother, Catherine de Vivonne, the Marquise, who disclosed to Julie that in the eyes of their friends, in high society, she was being seen as harsh and unyielding after Montausier had worked so hard to win her hand, that she was persuaded.

And so in April 1645, she said yes.

I think she also considered that from an old maid she became a new bride and then it put her back into the world again and she loves amusements very much.

Tallemant, Historiettes

There may have also been practical reasons for the marriage – both of the Marquise’s sons were dead, three of her daughters were nuns, and so they may have felt children were needed to inherit the Rambouillet wealth.

Their wedding was the highlight of the season. The formalities took place over several delightful summers’ days in July at the Château du Val de Ruel (now destroyed but in the area of modern Rueil-Malmaison), a few peaceful leagues from Paris. The original notation in the parish register for 3 and 4 July, 1645, reads that the marriage occurred between “Seigneur Charles de Sainte Maure, Marquis de Montauzier, Gouverneur for the king for the county of Xaintonge, and Lieutenant General for his majesties armies in Germany, and Damoiselle Julie Lucine d’Angennes of Rambouillet, daughter of Messire d’Angennes Marquis de Rambouillet”.

Married by her former suitor, Antoine Godeau, now the powerful Bishop of Grasse and Provence, the feasts, banquets, balls and fireworks at the beautiful château were only topped by the arrival of Les Vingt-quatre Violons du Roi, a five–part string ensemble at the French royal court.

Despite having finally made his romantic conquest, Montausier was supposedly surly and impatient during the celebrations, and on his wedding night was seen to throw his dressing gown into the room where his wife was waiting, ‘feverish’ with impatience.

The groom in truth had consummated the marriage but the rest of the night passed in conversations and good feelings, as he is younger than her. She is 38 years old.

Tallemant, Historiettes

Julie, now the duchess de Montausier, had 3 children over her married life. Their eldest daughter was Marie-Julie de Sainte-Maure, who would upon her marriage become Duchesse d’Uzès. Of her two sons, tragically, one died soon after birth and the other following a fall when he was three years old. She also suffered a miscarriage at the age of 51.

When Julie died on 15 November 1671, at the age of 64, her husband was inconsolable. His room at the Hôtel de Rambouillet was draped completely in black and servants could only appear before him in dark livery. After his own death 19 years later, their ashes were buried together in 1691, almost fifty years to the day he left the perfect book, La Guirlande de Julie, on her dressing table, and changed both their lives forever.

La Guirlande de Julie now rests comfortably at the Bibliothèque nationale de France.