“I met renowned masters, I used the best from their teaching and example. I found myself, I made myself, and I have said, I believe, what I had to say,”

Suzanne Valadon

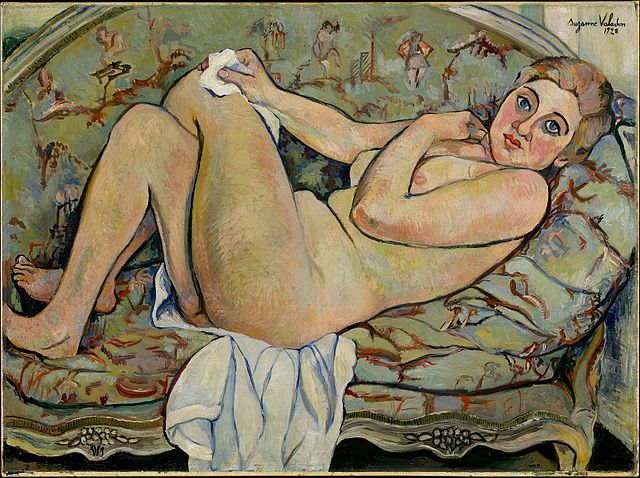

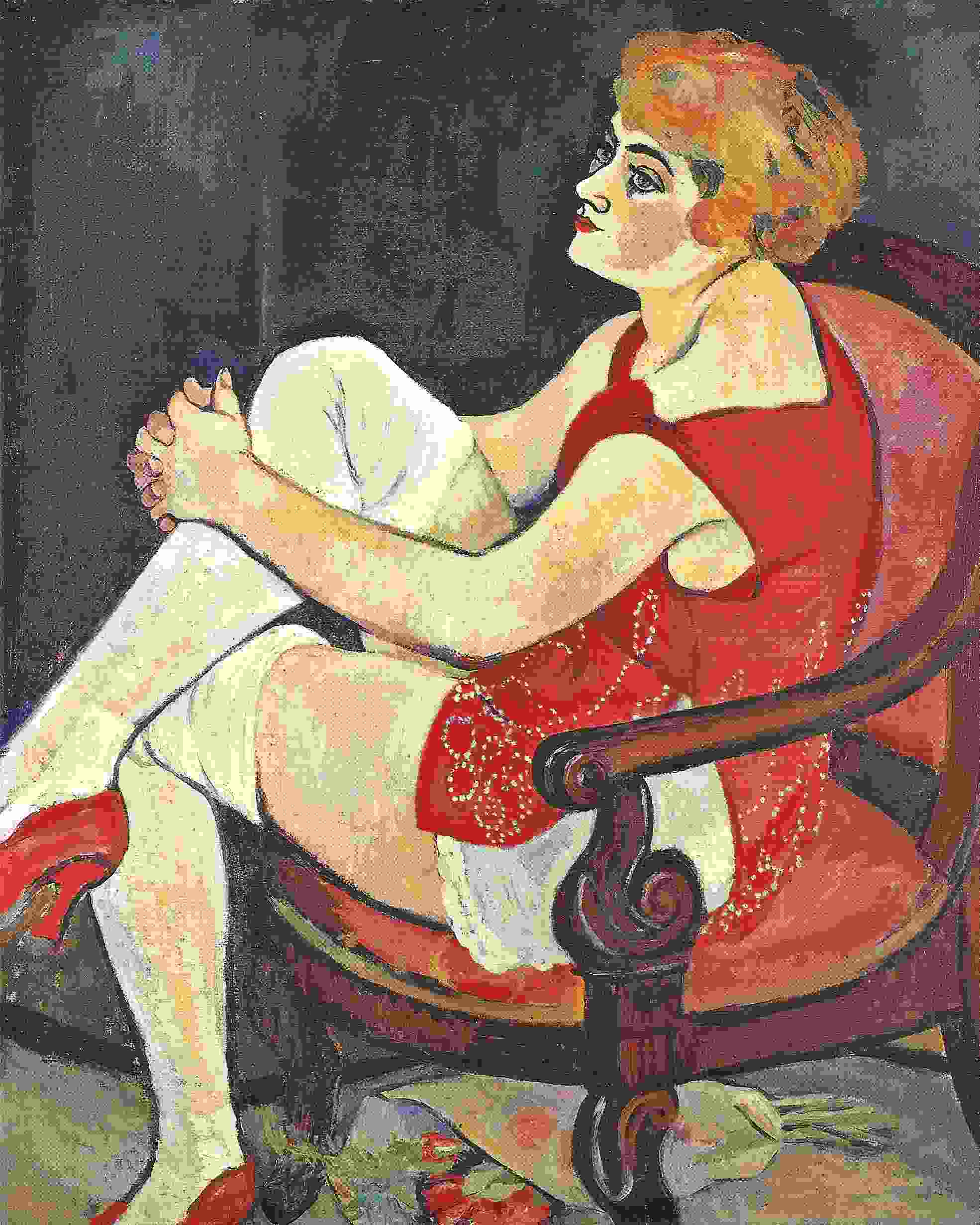

It’s easy to make Suzanne Valadon merely a footnote in the history of French art. Her body of work is often overshadowed by her body itself, laid bare on the canvases of artists such as Renoir, Degas and Toulouse-Lautrec. She is remembered more as a symbol of desire, seen only through the eyes of others, as model and mistress, and even the work of her own son, painter Maurice Utrillo was more famous than her own. But by creating her own interpretations of both the male and the female form, with her audacious nudes, bold lines and strong colours, Suzanne Valadon refused to be defined in what was essentially a man’s world, the artist’s world, and forged her own path.

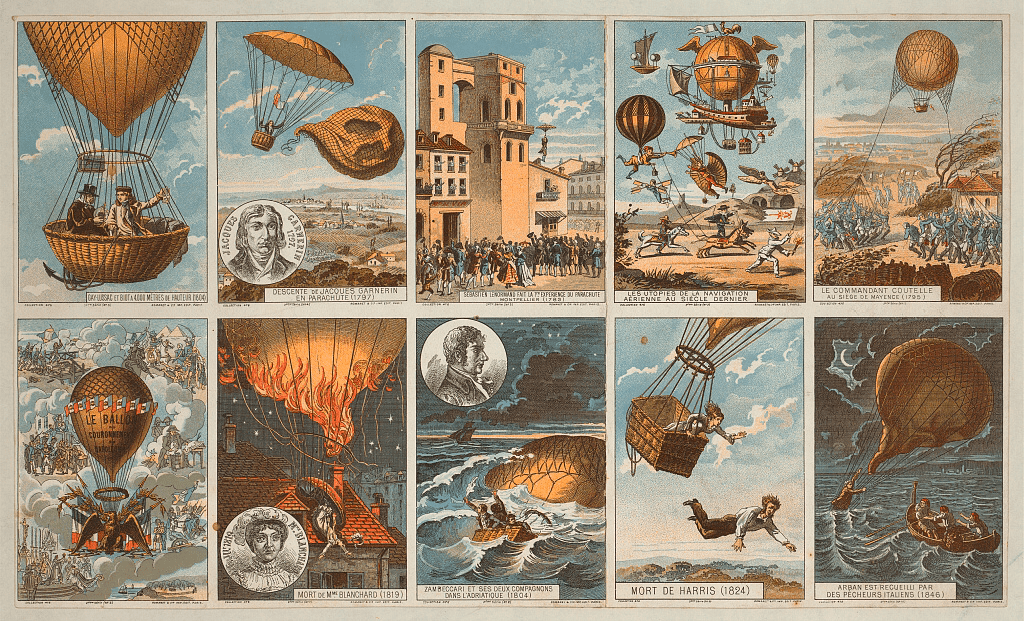

She was born Marie-Clémentine Valadon in the small rural commune of Bessines in 1865, not as the beloved child of an illustrious family left on the steps of the Limoges Cathedral as a baby, as she claimed, but the illegitimate daughter of a seamstress, Madeleine Valadon. Her father is unknown, but he was possibly a railway engineer who was working in Limousin at the time the chemin de fer was making its way through France. Madeleine took her baby girl to seedy Montmartre, Paris, where she worked endless hours as a housecleaner. From an early age Marie-Clémentine proved brazen and rebellious, as she would continue to be through her life, and she was expelled from her convent school aged twelve. She tried her hand as a stable groom, a vegetable seller and a garment maker, but her fiercely independent nature and fiery temper saw her change jobs often. She thought she had found her raison d’être when she joined the circus at the age of fifteen, but alas, a fall left her without the agility and flexibility she needed to be a performer. However, the months spent immobilised in bed after this accident allowed her to explore one of her secret passions – drawing.

Valadon recalled later that she had been obsessed by drawing since the age of eight, and had angered her mother to no end with her constant scribbling. Poor as they were, the young Marie-Clémentine likely relied on discarded scraps of paper and broken pencils.

The streets of Montmartre were Marie-Clémentine’s home, her ‘hood’. Montmarte was teeming with artists during the late 19th century, they drank and smoked and sketched and daubed, spilling onto the streets from bars and cafes and tiny rented studios. It was a crowded world, and very few made their fortunes. Soon after her accident, Marie-Clémentine became ‘Maria’, a voluptuous artists’ model soon in demand with her vibrant blue eyes and luxurious dark blonde hair. She lived close to Place Pigalle, where every Sunday was held a ‘Models’ Market’, in which men, women and children, all aspiring models, gathered hoping to be chosen by an artist in need of a sitter. The money earned by models, particularly those who agreed to pose nude was substantially higher than normal wages, but there was no guarantee of regular work.

“I remember the first sitting I did. I remember saying to myself over and over again, ‘ This is it! This is it!’ . Over and over I said it all day. I did not know why. But I knew that I was somewhere at last and that I should never leave…”

Recollection of Suzanne Valadon

Maria, who was very comfortable working in the nude, could sit for long hours in the same pose. She first worked with Pierre Puvis de Chavanne, known as the ‘Painter for France’ because of his large murals found in public and private buildings all over France. Maria continued to sit for Puvis intermittently for the next seven years and they were soon in a sexual relationship. Artists’ models becoming ‘mistresses’ was a cliché because it happened all the time – young women, usually poor and often naked, sitting for hours alone in the company of a male artist, were oftentimes expected to provide sex as part of the job description. Many would succumb, doubtless because the title of mistress could lead to financial security and recommendations for other modelling jobs for the future.

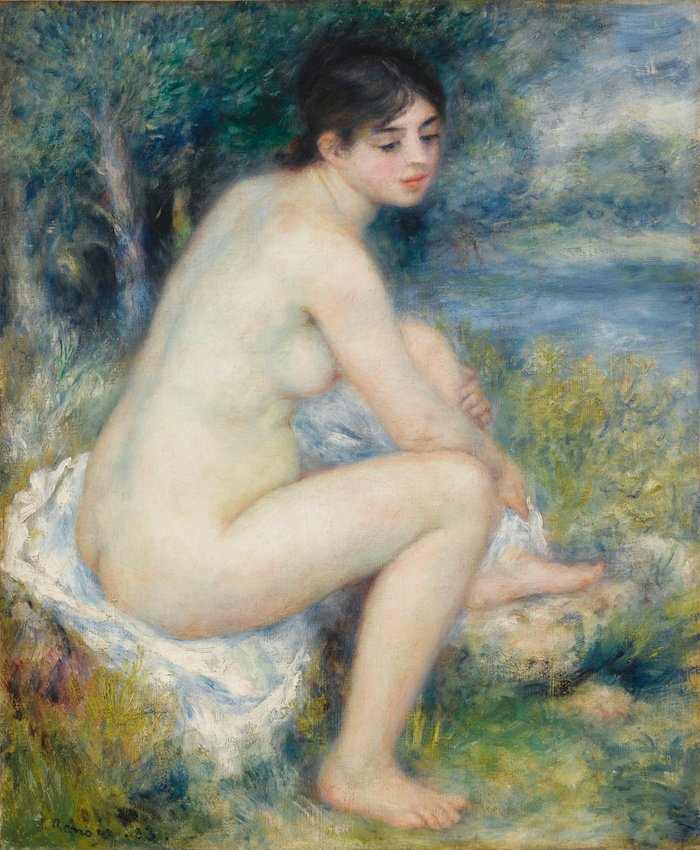

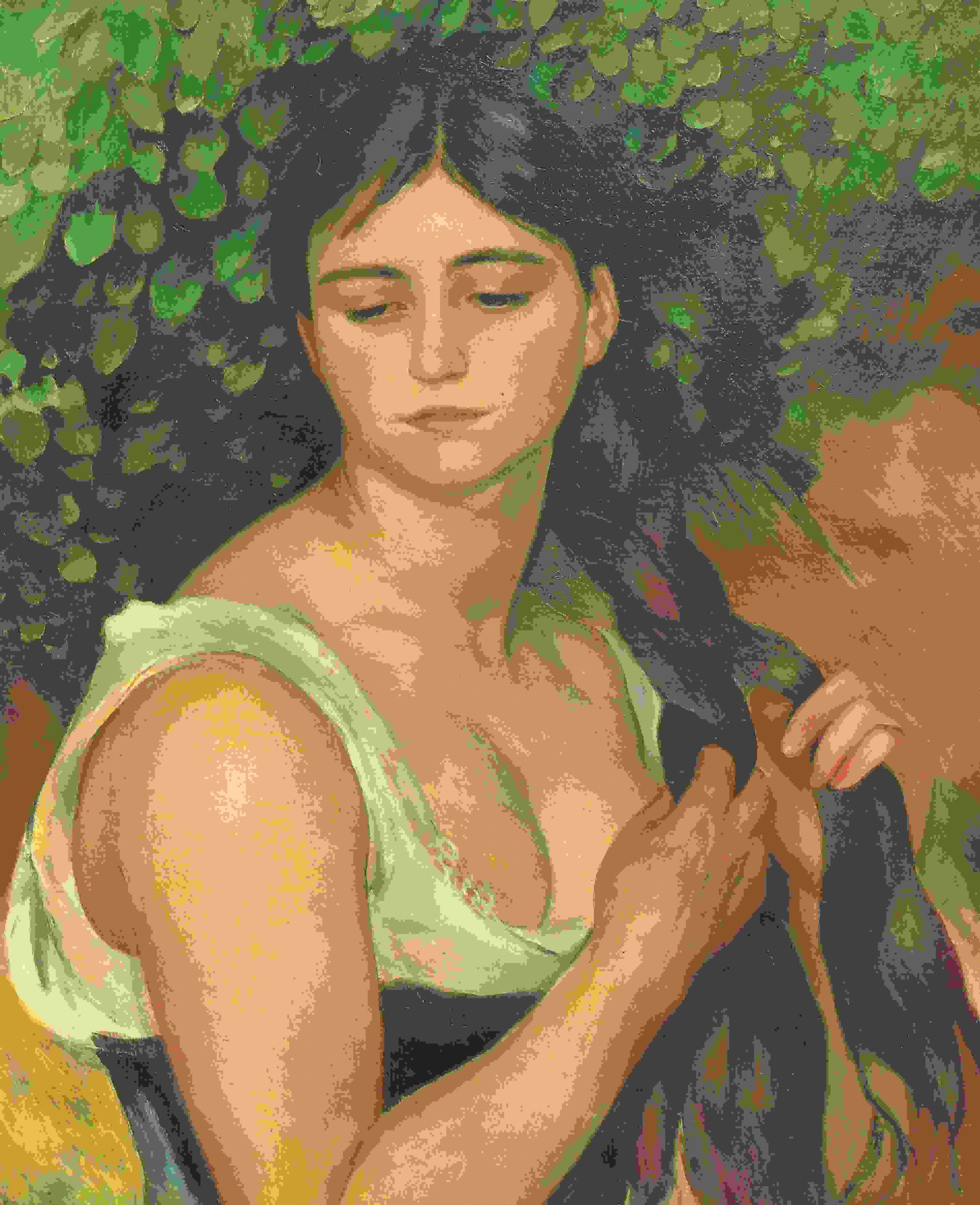

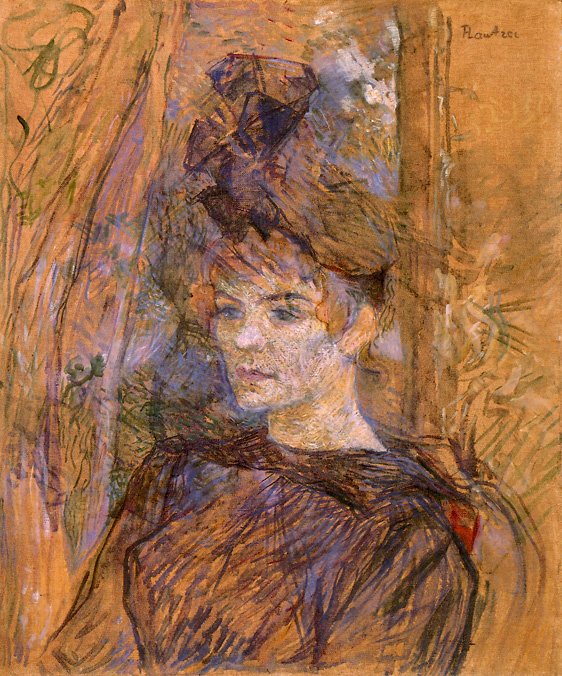

‘Maria’ was the model in all three of these paintings

In truth, it was a murky world, but for Maria it meant escaping her dreary tenement room to join the enchanted circle of artists, poets and musicians in Montmartre. She modelled for ten years, and had many lovers amongst the artists she posed for, including Pierre-Auguste Renoir, but very few knew of her own talent as an artist.

Inevitably, at the age of 17, she fell pregnant. Her son, named Maurice, was born in December 1883 in her tiny flat to ‘Marie-Clémentine Valadon and unknown father’. She refused to name the father and told her friends, “It is difficult to tell since actually I don’t know myself”. The main contender was Miquel Utrillo, scion of an aristocratic and wealthy Catalan family. Born in Barcelona in 1862, his parents were political émigrés in Paris. He, like so many, also aspired to be an artist, and had rented a room in Montmartre as a studio. Valadon later recalled: “With Miquel, I had the best years of my youth…he encouraged me and gave me strength… we lived like artists and bohemians”. She had moved with her mother and son to a larger, three-roomed apartment after the birth of the baby, and had a secret source of income which supported her throughout the pregnancy when she couldn’t work, another reason to suspect the moneyed Utrillo to be the father of her child. He formally recognised Maurice as his son in 1891 but left Paris soon after.

Known for her joie de vivre, her son was left with his old, illiterate but loyal grandmother while ‘Maria’ modelled during the day and partied at the cabarets and music halls at night such as Le Lapin Agile, Le Chat Noir, and Le Mirliton – a model needed to be seen and heard.

Her most tumultuous affair was for several years with the aristocrat painter, Vicomte Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. Lautrec moved to Montmarte in 1884 and was soon using Maria as his model and mistress. Seen all over Montmartre in nightclubs, their relationship was stormy and marked by frequent quarrels. Lautrec began to question whether Maria was only interested in his money, and in a last-ditch attempt to regain his favour, she staged an elaborate suicide attempt which only served to end their affair. However, it was through Toulouse-Lautrec that she was able to make the leap from poser to painter. Voicing his opinion that “You don’t stand a chance at a career if your name conjures images of fruit”, he christened her Suzanne, after the famous bible story Susannah and the Elders, in which Susannah, preparing for her bath, is spied upon by two old men who later make sexual advances which are repudiated. Whether he saw Maria/Suzanne as a naked temptress or as a strong-willed female figure is not known. Luckily, Toulouse-Lautrec was a great believer in Suzanne as an artist, and it was he who painted ‘Madame Suzanne Valadon, artiste peintre’, in 1885 which for the first time acknowledged her as an artiste and gave her respectability.

For a long time, as ‘Maria’, Suzanne Valadon had dressed or undressed as demanded, worn costume, acted a part; it was all make-believe. When her son was born she realised just how passionately she wanted to become a professional artist, to “capture a fleeting moment of life in all its intensity”. Her son Maurice was sketched standing near the bathtub, or as he slept, and her mother was painted as she sat in her chair.

But in the late 19th century, it was all but impossible for a working class woman to become an artist. Wealthy women could afford to study in private classes or academies. Berthe Morisot, the Impressionist painter, came from a prosperous family and was the great-granddaughter of the famous painter Fragonard, so she had the means and opportunity to follow her dreams. Her drawing master warned her parents: “with my teaching they [she and her sister] will become painters…in the upper class milieu to which you belong, this will be revolutionary, I might say catastrophic”.

But Valadon had something Morisot didn’t – intimate access to the most famous painters of the day. Unbeknownest to the artists for whom she posed, Valadon was observing, scrutinising, criticising and most importantly, learning their art. On one occasion Renoir caught her drawing and supposedly exclaimed: “You too!… and you hide it…”, though he did nothing to help her. In 1894, introduced by Toulouse-Lautrec, she met Edgar Degas, who was known chiefly for his depictions of ballet and ballerinas, and they began a friendship and correspondence which would last for many years. While Degas was known to be somewhat callous in his attitude to his female models, (“I have perhaps too often considered woman as an animal,” he once told the painter Pierre Georges Jeanniot), when he examined her etchings he declared: “You are one of us!” At first he did not believe that a working woman with no formal training could have produced works of such beauty, but he soon collected and proudly displayed her works next to those of Manet and Gauguin in his apartment. “Cette diablesse de Maria avait le génie du dessin!” was his affectionate expression of his admiration for her. Rumours swirled that she was Degas’ mistress, which she strongly denied, and their letters show that their friendship was based on mutual respect rather than sex. On his death he was found to have 17 drawings and three prints (all nudes) by Suzanne Valadon, amidst a staggering collection of talent which included Morisot, Cassat, Delacroix, Pissarro, Gauguin, Renoir, Sisley, Cézanne and Van Gogh.

Encouraged by Degas, in 1894 she submitted her drawings to the prestigious Salon de la Sociète Nationale des Beaux -Arts, held in a pavillon on the Champ-de-Mars. Five of her works were accepted and she was the only female exhibitor.

In 1895 Suzanne Valadon married Paul Moussis, a wealthy stockbroker, with whom she had been having an affair for five years. Valadon gave up modelling and they moved to Pierrefitte, a small town north of Paris. Her son Maurice was now 13, unable to stay in school or remain in any job, and already spiralling into alcoholism. She now used only the name Suzanne, committed as she was to carving a respectable – although unconventional – bourgeois life and focus on her art.

In 1901 Maurice was diagnosed with precocious dementia or schizophrenia and kept for two months in an asylum. His fits of violence and drinking continued. Painting as a form of therapy was suggested, and whilst it did not cure his medical issues or addiction to alcohol, it revealed his talent as an artist.

Despite her growing success, Suzanne was becoming desperately bored with suburban life, and longed for the bright lights and seedy underbelly of her beloved Montmarte. She divorced Paul Mossis and moved herself, her mother, her son, two dogs and a new, golden-haired, young lover back to Paris. This young man was André Utter, an aspiring artist himself, and 20 years younger than Suzanne, who was aged 43. With his handsome looks and boyish charm, he encouraged Suzanne to take up her brushes again and soon she was showing her paintings at the Salon d’Automne in 1909 and at the Salon des Indépendants in 1910, marking the beginning of an intense artistic period.

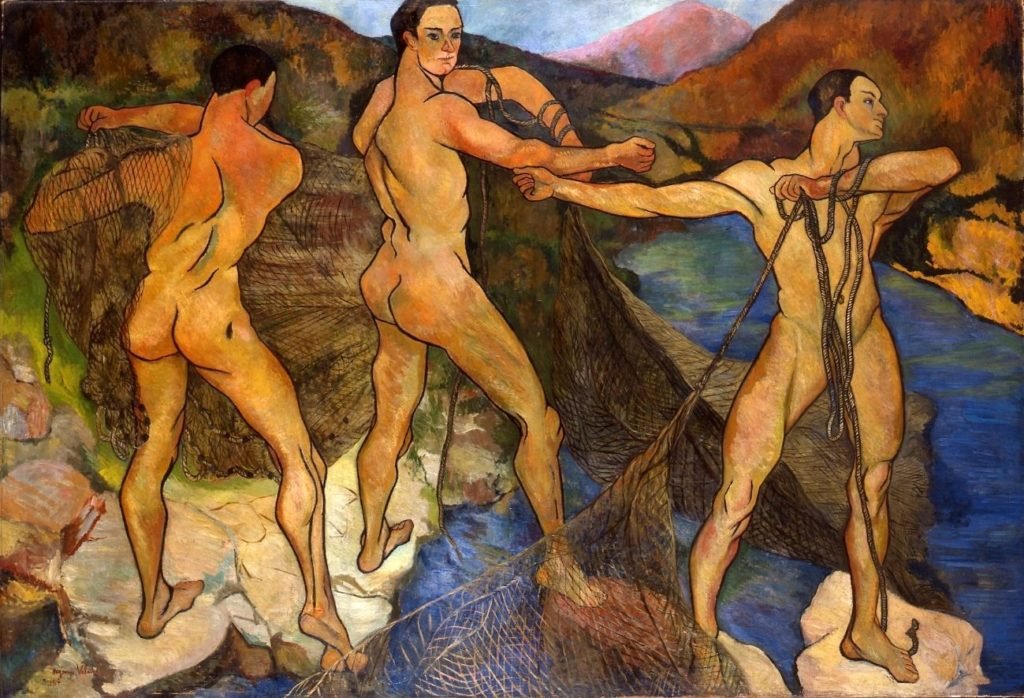

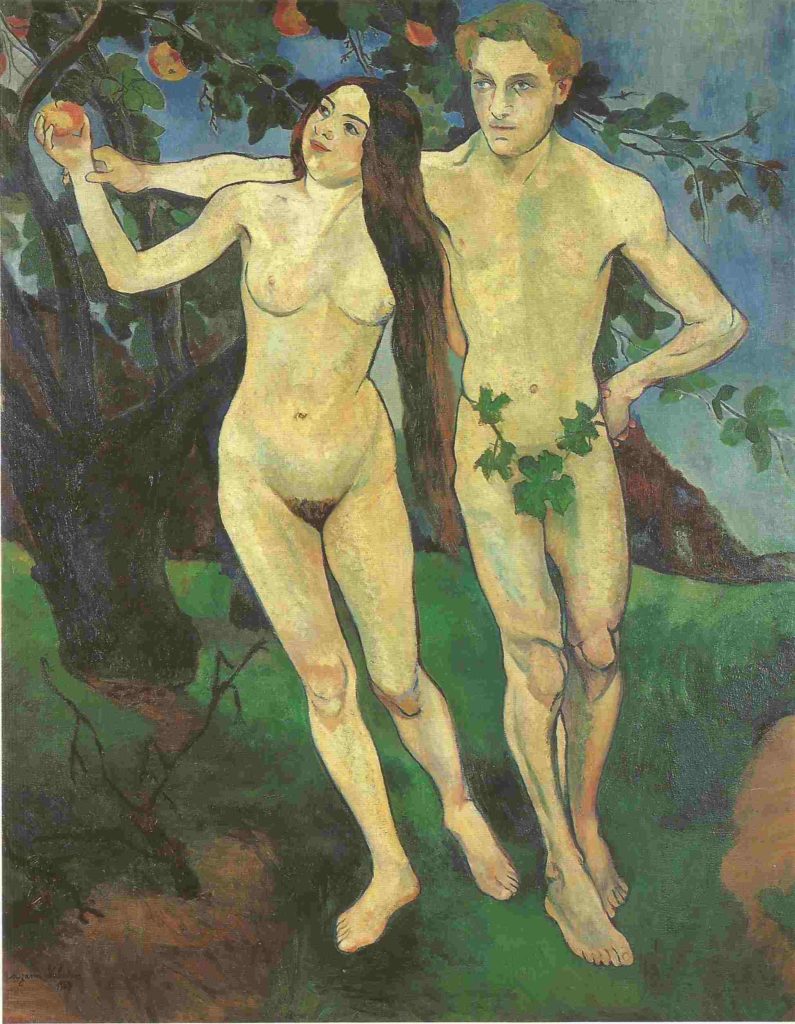

Her success emboldened Suzanne to paint nudes – while this was a common subject for male painters, it was exceptionally daring for a woman to do so. In 1909 she and Utter were the models for her own work Adam and Eve, the first painting by a woman of a naked male and female together (when this work was sent to the Indépendants in 1920, she had to add vine leaves over Adam’s naughty bits for fear of offending). Her Lancement du filet (Throwing the nets), with three nude male figures, was posed for by Utter on a trip to Corsica and was ground-breaking not only for its male nudity, but for casting the men as objects of desire. However, this was the last male nude painting she produced and she focused on images of women and children. What was radical about Valadon’s nudes was their lack of coyness or seduction. Instead, their bodies were awkwardly posed and often distorted, preparing for a bath or leaning on a chair, far from the stereotypical image of a sensual woman.

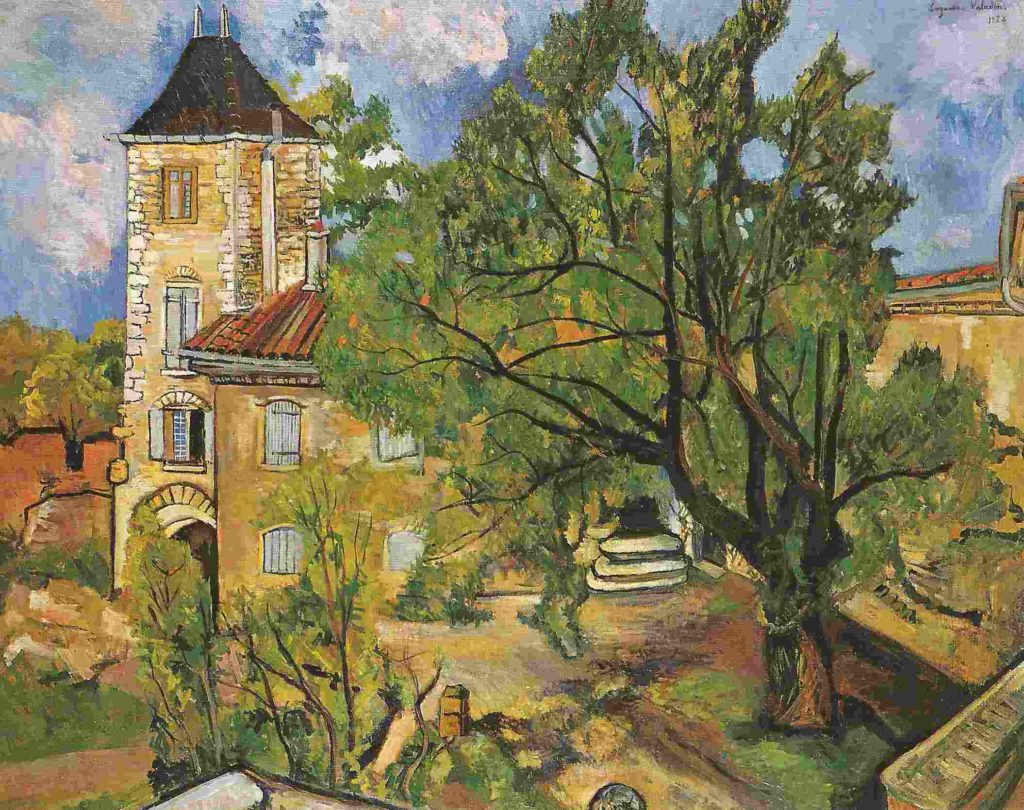

The roaring twenties saw more success for Suzanne Valadon, and the purchase of the 13th century Château Saint-Bernard near Lyon, with its picturesque moat and drawbridge, as well as drafty rooms and cold water. Utter and Suzanne held many parties here and feted the crème de la crème of Parisian art society, but behind the scenes their marriage was as crumbling as the castle walls. Utter’s infidelities were an open secret and by 1926 she and Maurice were back in Montmartre living in an modern Art Nouveau residence.

I beg forgiveness from my Suzanne, my wife who makes me proud and whom I love. I beg forgiveness for the harm I have caused her with my insults and angers that keep her from living in peace.’

Letter from André Utter, 1925

At last it was becoming a little more acceptable to be a female artist. The state-funded Ecole des Beaux-Arts had opened its doors to women students at the turn of the century, and their work was often accepted in salons and galleries. However, there was always misogyny, with a contemporary writer emphasising: “Women painters threaten to become a veritable plauge, a fearful confusion and a terrifying stream of mediocrity. A perfect army of women painters invades the studios and the salons…”. Female artists were often expected to provide sexual favours in exchange for showings by art dealers and collectors. The Russian artist Maria Vorobev, who worked in Paris at this time complained: “Being a woman and a painter does not mean that one is a whore!”.

The Great War was a desperate time for Suzanne Valadon. She and André had married in 1914, but as he was away for much of the war she found herself often penniless. Maurice was hospitalised frequently, her faithful mother Madeleine died in 1915 and her friend Degas in 1917. With the end of the war came Utter’s safe return, as well as Suzanne’s enthusiasm for art and a burgeoning fame. However, the relationship between she and Utter, which had always been volatile due to her restlessness and quick temper, became even more so. Maurice Utrillo’s fame and fortune was blossoming as his mental state was declining, and the three were known as the ‘Damned Trinity’ as they were forever attracting public scandal and gossip with their now extravagant life.

The 1930s were Suzanne’s most successful years, even as her health began to decline. Despite her work lacking the ‘womanly’ element so prevalent in female art of the time, she (reluctantly at first) exhibited her work in the Salon of Modern women painters from 1933 until her death. But even though she was well-known all over the world and sold many of her paintings, it was her son’s art which brought in the money. Even today she is often referred to as merely the mother of Maurice Utrillo. When he married in 1935, his ambitious wife encouraged him to leave the mother with whom he had lived for most of his life. She took control of the earnings from his paintings and Suzanne was left with no money. She spent much of her time painting flowers, which she loved and called ‘her friends’. Still living in her Montmartre, she died of a stroke on 7 April 1938, whilst seated at her easel. All of Paris attended her funeral at Saint-Pierre-de-Montmartre church, except her son. She was buried near her mother in the cimitière de Saint-Ouen.

The roaring twenties saw more success for Suzanne Valadon, and the purchase of the 13th century Château Saint-Bernard near Lyon, with its picturesque moat and drawbridge, as well as drafty rooms and cold water. Utter and Suzanne held many parties here and feted the crème de la crème of Parisian art society, but behind the scenes their marriage was as crumbling as the castle walls. Utter’s infidelities were an open secret and by 1926 she and Maurice were back in Montmartre living in an modern Art Nouveau residence.

In almost everything that has been written about Suzanne since her death, she has been censured for neglecting her illegitimate son, for her bohemian way of living and for a lack of femininity in her paintings and drawings. She is usually described as having a voracious sexual appetite and a vicious temper. Such criticisms, focusing on the (female) person and not the paintings, have cast a shadow on her right to be considered seriously as an artist. She was, after all, a woman daring to shine in a man’s world. In order to succeed she overcame greater obstacles than any other woman artist of her time, but her background and self-reliance gave her a sweeping insight into the harsh realities of working class life, which lend her paintings and drawings such forcefulness. Her stories to the press may have been made up, but her paintings were honest until the very end – her final self portrait at the age of 66, is aching in its candor.

Suzanne Valadon wanted not to be known as a ‘woman artist’ but merely as an artist, and looking at a painting of beautiful flowers in a vase or a striking nude, the question of her gender seems quite irrelevent.

“My work is completed, and the sole satisfaction it brings me is that I never betrayed not abandoned any of what I believed in”.

Suzanne Valadon to a friend, shortly before her death.

The Musée de Montmartre, located at 8-14 Rue Cortot, has reconstructed the atelier-apartment at 12 Rue Cortot where Suzanne Valadon, her son and André Utter settled in 1912, faithful to the letters and writings of the time and as portrayed in historical photographs.

If you would like to have some Suzanne Valadon on your walls, here is the link to my Etsy shop

Hello. So nice to hear from you.

What an interesting woman. It is so typical of woman of that time to be remembered for their exploits and not for their talent. Her color palette, and even her style to a certain degree, remind me a bit of the Mexican artist, Frieda Kahloe.

Hello! You are so right, there are definite similarities to the works of Frieda Kahloe, both women who refused to conform to society’s expectations and stereotypes.