On 21 April, 1770, when Marie-Antoinette left Vienna to become Queen of France, she knew she would never return.

‘Farewell, my dearest child. A great distance will separate us … Do so much good to the French people that they can say that I have sent them an angel.’

Maria Theresa, Empress of Austria, to Marie-Antoinette on her departure

{Related post: The life of Marie-Antoinette – childhood}

At the border of Austria and France there occurred the handover, a ‘de-Austrification’ ceremony, where Marie-Antoinette was completely divested of her Austrian clothing, even down to her ‘body-linen and stockings’ and dressed in the clothes presented to her by the French court. A foreign princess had always to renounce all inherited titles before marriage, and could retain nothing belonging to a foreign court.

Essentially she was a royal package, sealed with the double-headed eagle of the Habsburgs and the fleur-de-lys of the Bourbons.

Antonia Fraser, Marie Antoinette: the journey, 2001

dauphine

Marie-Antoinette met her husband (despite having never set eyes on each other they had been married by proxy one month earlier) in the forest of Compiègne, where they exchanged a very formal embrace. Louis later wrote in his diary, which was reserved for hunting and important events: ‘Meeting with Madame la Dauphine.’

The official marriage ceremony took place the following day, 14 May, 1770, in the royal chapel at Versailles.

The dauphiness, then [almost] fifteen years of age, beaming with freshness, appeared to all eyes more than beautiful. Her walk partook at once of the noble character of the princesses of her house, and of the graces of the French; her eyes were mild – her smile lovely.

Memoirs of the Court of Marie Antoinette, Madame Campan, 1843

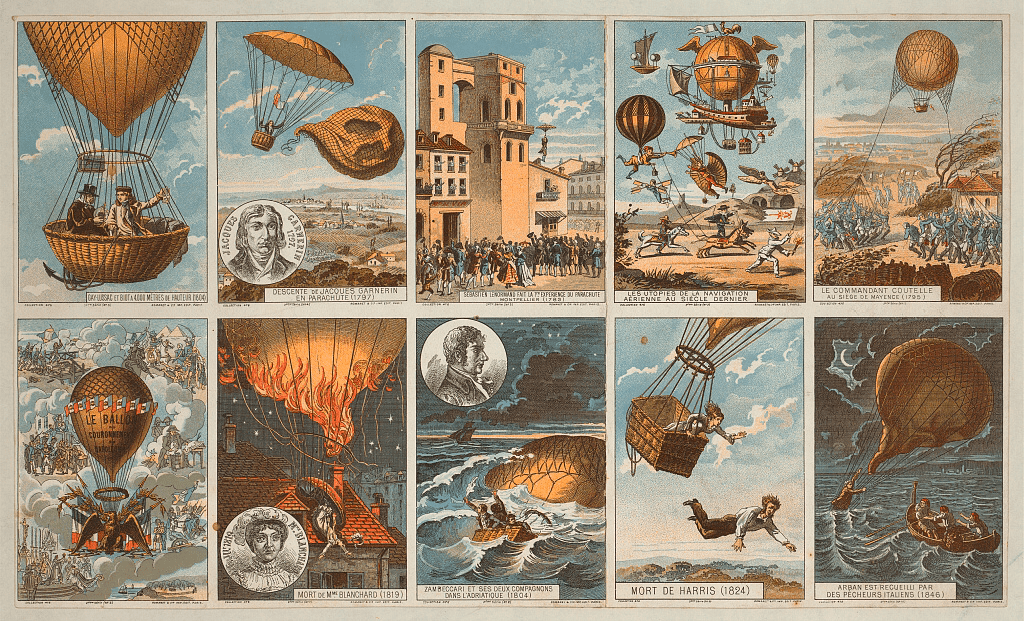

A succession of balls and banquets celebrated this happiest of events. However, a fireworks display gone wrong cast a gloomy pall over the last day of the wedding celebrations:

Three sides of the Place Louis XV were filled up with pyramids and colonnades. Here dolphins darted out many-coloured flames from their over-open mouths; there, rivers of fire poured forth cascades spangled with all the variegated brilliancy with which the chemist’s art can embellish the work of the pyrotechnist. The whole square was packed with spectators, the pedestrians in front, the carriages in the rear, when one of the explosions set fire to a portion of the platforms on which the different figures had been constructed. Panic succeeded to delight, and the terror-stricken crowd, themselves surrounded with flames, began to make frantic efforts to escape from the danger… in a few moments the whole mass, human beings and animals, was mingled in helpless confusion, making flight impossible by their very eagerness to fly, and trampling one another underfoot in bewildered misery.

Charles Duke Yonge, The Life of Marie Antoinette, Queen of France, 1877

In all, 130 people died in the tragedy. The Dauphin and the Dauphine were devastated and both gave their monthly allowances to assist the families of the dead and wounded.

In hindsight, was this an ominous sign of the future? Many in the crowd would, 23 years later, in the exact same place, watch and cheer as first Louis and then Marie-Antoinette were led to their deaths by guillotine. But that is for the future.

everyone loves Marie-antoinette

On another happy occasion, three years into their marriage, jubilant and adoring Parisians turned out in their thousands to catch a glimpse of the young and vibrant Dauphine on her first official visit to Paris.

On Tuesday I had a fête which I shall never forget all my life. We made our entrance into Paris. What was really affecting was the tenderness and earnestness of the poor people, who, in spite of the taxes with which they are overwhelmed, were transported with joy at seeing us. When we went to walk in the Tuileries, there was so vast a crowd that we were three-quarters of an hour without being able to move either forward or backward. The dauphin and I gave repeated orders to the Guards not to beat any one, which had a very good effect. Such excellent order was kept the whole day that, in spite of the enormous crowd which followed us everywhere, not a person was hurt. When we returned from our walk we went up to an open terrace and stayed there half an hour. I cannot describe to you, my dear mamma, the transports of joy and affection which every one exhibited towards us. Before we withdrew we kissed our hands to the people, which gave them great pleasure. What a happy thing it is for persons in our rank to gain the love of a whole nation so cheaply. Yet there is nothing so precious; I felt it thoroughly, and shall never forget it.

Letter from Marie-Antoinette to her mother, June 1773

the art of surviving versailles

Marie-Antoinette had been a royal all her life; she knew about court etiquette, how to be on public display. But nothing prepared her for life in the royal court of Versailles, with its traditions and rituals, and nobles and courtiers maneuvering and scheming for personal gain. Even more complicated, however, was the simple act of getting dressed.

One of the traditions most unpleasant to Marie-Antoinette was that of dining every day in the public eye. Any person who was decently dressed was able to enter Versailles (swords for men were recommended) and watch the royals as they ate their meals. Each separate branch of the family dined separately – the dauphin and dauphine together – and it was the delight of visitors to watch “the dauphiness take her soup, then see the princes eat their bouilli [stewed meat], and then run till they were out of breath to behold Mesdames at their dessert.”

queen of france

In 1774, life at Versailles changed immeasurably when Louis XV was struck down with a rather nasty strain of smallpox. As his life was extinguished, so too was the candle in the window, the sign that he lived no more.

The dauphin was with the dauphiness. They were expecting together the intelligence of the death of Louis XV. A dreadful noise, absolutely like thunder, was heard in the outer apartment: it was the crowd of courtiers who were deserting the dead sovereign’s anti-chamber, to come and bow to the new power of Louis XVI. This extraordinary tumult informed Marie Antoinette and her husband that they were to reign; and, by a spontaneous movement, which deeply affected those around them, they threw themselves on their knees; and both pouring forth a flood of tears, exclaimed, “O God! guide us, protect us, we are too young to govern.”

Memoirs of the Court of Marie Antoinette, Madame Campan, 1843

Too young or not, when Marie-Antoinette was Queen consort of France, one of the first things she did was to remove herself from the public eye to eat her dinner in relative peace.

fashion icon

It is well known that the queen showed exquisite taste when it came to fashion. A generous allowance also helped. Her designer, Rose Bertin, was one of very few of her ‘station’ allowed to enter the inner sanctum of Marie-Antoinette’s apartments, and profited greatly from the privilege. This also meant that new fashions could be introduced almost daily, and copied almost immediately by the women in Versailles and Paris.

For the winter, the Queen had generally twelve full dresses, twelve undresses, called fancy dresses, and twelve rich hoop petticoats for the card and supper parties in the smaller apartments. She had as many for the summer. Those for the spring served likewise for the autumn. All these dresses were discarded at the end of each season, unless indeed that she retained some that she particularly liked. I am not speaking of muslin or cambric muslin gowns, or others of the same kind; they were lately introduced; but such as these were not renewed at each returning season, they were kept several years.

Memoirs of the Court of Marie Antoinette, Madame Campan, 1843

According to Madame Campan, the pouf, the elaborate head-dress, with its gauze, flowers and feathers, arose to such a degree of loftiness, that the women could not find carriages high enough to admit them; and they were often seen either stooping, or holding their heads out at the windows. Others knelt down in order to manage these elevated objects of ridicule with the less danger. Marie-Antoinette did not actually popularise the pouf, its existence at Versailles predated her arrival, but her hair was raised and powdered and puffed like all the other women.

Despite the later accusations of frivolity thrown at the queen, she in fact preferred a simpler form of dress, and was much happier in her classic while muslin gown than the rigid court dress, with its unforgiving panniers and train. She was also very happy to forego the heavy makeup and rouged cheeks so beloved by the nobility and royals. You will all have seen the 1783 portrait by Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun, where Marie-Antoinette wears her loose, white dress tied at the waist with a golden sash, a few ruffles and ribbons for effect, and a straw hat with a fabulous feather. Whilst scandalous at the time for a queen to dress so plainly, the look was soon widely copied.

marital duties

Was she happy at Versailles, one of the most beautiful palaces in the world? Despite her life of luxury, the marriage of Marie-Antoinette and her husband was at first on rocky ground. Their wedding night, solemnised with the blessing of King Louis XV who gave the young Louis-Auguste his nightgown and personally handed him into bed, had by all accounts been an enormous failure. The bride and bridegroom were only aged 14 and 15 at the time, but this was the 18th century and ‘relations’ were expected, especially with young royals. According to sources, the dauphin Louis was very bad tempered the following morning and very rudely left his new wife to go hunting. Louis XVI loved hunting, and recorded his catch in his diary every day. When he wrote “rien (nothing)”, it may just as well have referred to his exploits (or lack of) in the bedroom.

Frustratingly for Marie-Antoinette, not only as a young woman but with the added pressure of producing an heir, it was a long seven years before there was any real action in the royal bedroom (perhaps the menacing image of the double-headed Austrian eagle over the bed was too distracting).

Much has already been written about and speculated on as to why Louis XVI was unable or unwilling to consummate the marriage.

The notion is now discounted that Louis suffered some physical malformation such as phimosis or a tight foreskin, which made erections painful: the numerous medical examinations ordered by an anxious Louis XV, worried about the continuation of his dynasty, revealed nothing abnormal about his heir. Instead most people put the couple’s problems down to a combination of coldness towards her husband amounting almost to frigidity on Marie-Antoinette’s part and a staggering lack of technical knowledge on the part of Louis.

John Hardman, Marie-Antoinette – the making of a French Queen, Yale University Press, 2019.

With nothing escaping the notice of even the smallest minion in the palace, it became a much-discussed topic. Her mother, Maria-Theresa, who continued to write to her daughter regularly and used her ‘spies’ at the court to report on Marie-Antoinette’s behaviour, had much to say on the matter. She believed it was the duty of the wife to ‘caress’ and provide ‘redoubled caresses’. In no uncertain terms, she told the new queen:

‘Everything depends on the wife, if she is willing, sweet and amusante.’

queen and mother

Finally, to the joy of all the kingdom (except the brothers of Louis XVI, next in line to the crown), the king was performing his marital duties with aplomb and Marie-Antoinette became pregnant in 1777. Generous and kind-hearted as she was, when she made the announcement of her pregnancy she gave 12,000 francs to those debtors in jail in Paris who had been unable to pay their wet nurses, and to the poor of Versailles.

The baby, a girl, was born on 11 December 1778. The custom at Versailles was that anyone who was anyone was allowed to watch the birth. The queen’s bedroom became so crowded with onlookers (two men climbed onto furniture for a better view) that Marie-Antoinette started convulsing and passed out with the lack of air. She regained her senses when the windows were finally opened, the unwelcome visitors were dispersed of, and her foot had been ‘bled’. This was the last time this archaic custom was observed at the palace of Versailles.

The baby girl, Marie-Thérèse Charlotte, may have been a disappointment to Louis XVI and the nation but to Marie-Antoinette, she was finally able to be the mother she had wanted to be for so long. She even breastfed the baby for a time, which was not encouraged amongst the elite. In 1781 she gave birth to her second child; the silence following the birth caused her to think it was another girl. An awestruck Louis XVI leaned in and whispered lovingly in her ear:

‘Madame, you have fulfilled our wishes and those of France, you are the mother of a Dauphin.’

The baby was named Louis Joseph, the long-awaited heir to the throne. He was taken from the queen almost immediately and paraded down the street by the royal governess, as heirs to the throne were not to be raised as normal children. Louis Charles was born in 1785, and her fourth child, Marie Sophie Hélène Béatrix came into to the world in 1787 but sadly, left it only 11 months later.

The life of Marie-Antoinette would soon become more complicated, with political intrigues, scandalous and libelous accusations, and an affair with a diamond necklace from which she could not recover.

Stay tuned next week, same time, same place, for Part 3 of the life of Marie-Antoinette.

further links

Do you want to get up close and personal with Marie-Antoinette? Take a 360 degree tour of her bedroom in Versailles.

Without Madame Campan, this article would not have been written!

Meet Marie-Antoinette, Queen of France, and her children by Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun

Get a head start on next week’s article and take a virtual tour of the Queen’s Hamlet in Versailles

Do you adore Marie-Antoinette like me? Leave me a message in the comments below.