Ah, the Belle Époque in Paris. A whirlwind of balls, galas, theatre, can-cans at the Moulin Rouge and gilded ceilings at the Paris Garnier Opéra house. Women dressed in their finest met at five o’clock at the house of Paquin to order yet more feathers, flounces and bustles, and the fashionable showed off the latest style at the races at Longchamp. As the century turned and all that was old was new, life seemed full of possibilities.

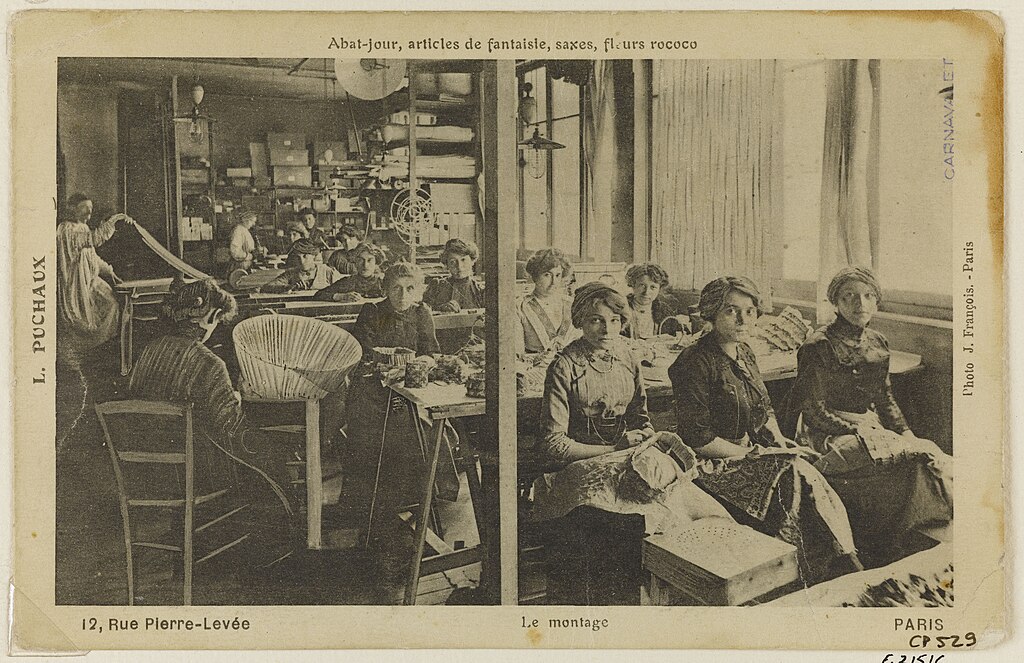

But not for these sixty-seven factory workers, or ouvrières, who sat for this photo in 1900. Did they have dreams, or hopes for the future? How many would ever have the opportunity to leave the factory? Women have worked since the beginning of time, in the home, in their own businesses or in the fields, but with the advent of industrialisation the second half of the 19th century was all about economic growth. Materialism was rampant and mass entertainment was taking hold, and women were needed to work in factories to satisfy such demands. They sent their babies to be raised by wet nurses in the quiet countryside and endured the low pay and back-breaking conditions of women’s labour.

The unknown women seated in front of their factory manufactured the magnificent decor and stage sets of the Opéra Garnier. Their day began bright and early at six o’clock, and they remained at the factory until 7pm. One half an hour was allowed for a mid-morning break, and another in the afternoon. Afterwards they walked home, usually to the poor workers’ faubourgs in Paris, where they ate a meagre meal. In 1900, a kilo of bread meant two hours of work, and four hours for one kilo of sugar. A bottle of champagne would cost them a half-day of work, and a box seat at the Opéra was the equivalent of four months’ salary!

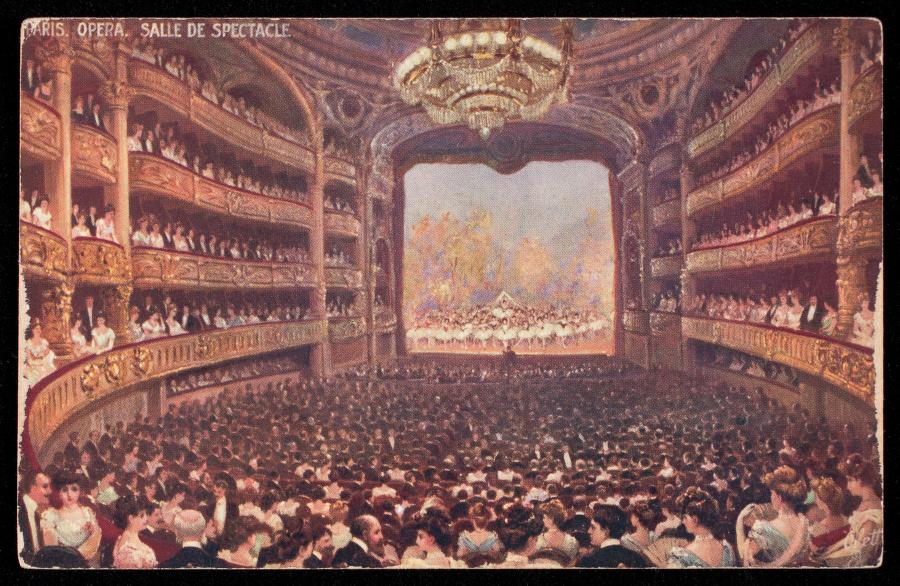

These working women would never know the luxury of watching a performance, but those rich enough in Paris in the Belle Époque, glided along the grand staircase and gazed upwards at the ornamented and lustrous canopy of marbled friezes, their diamonds outshone only by the glass chandeliers and glittering mirrors. As they gasped and gaped at the spectacle of the opera, most of them there just to be seen anyway, they sank luxuriously into the red velvet of the loges and watched Renée Vidal sing Aïda, surrounded by faux Egyptian pillars and hieroglyphs made in the factory.

There were 19,745 million women in France in 1906. The vast majority were still living in rural areas, but a significant 22% of women were working in the non-agricultural labour force. Of these, around one million were waged labourers, the ouvrières, employed in the manufacturing industry. The typical worker was a single young woman, but all too often a family’s economic survival depended on a women’s income, so married women could be engaged in factories.

For these working women the days were long, the work was arduous and the conditions were atrocious. Even if they were the breadwinner for the family, a woman’s wages were not even half of what a male factory worker would receive. In case of illness or pregnancy, there was of course no pay.

Jeanne Bouvier, daughter of a small cooper and small farmer in the Isère, became an ouvière in 1876 aged only eleven. She started work at 5am and finished at 8pm. There were several breaks for meals, totalling two hours, and she was paid 50 centimes for the whole day. On this deplorable salary, the needs of the family meant she also gave up her nights to earn money.

“I recall that one time among others I went almost two days without eating. In the evening, on coming home from the factory, I got down to work (crocheting in the evenings). My mother spent the night with me to give me a shake when in spite of myself I fell asleep. She said “don’t go to sleep, you know that you mustn’t sleep. Tomorrow we won’t have any bread”. I kept working until 4.30am, the time at which I got ready to return to the factory”.

Women in the textile mills in the north of France often fared even worse, where they worked 12-14 hour days in dangerous conditions, forced to clean their machines during their break times. Rape, sexual harassment, physical violence and verbal abuse were constant fears.

In the Belle Époque in Paris, wealthy women danced until all hours in frills and lace while other women spent their evenings sewing this frippery in the latest fashion houses, where employment was precarious and salaries often worse than in the factories. In the textile industry work was often seasonal. Before a grand event extra seamstresses would be needed and would work all hours. One inspector found that prior to a Grand Prix race in 1900, dressmakers had worked non-stop for 30 hours.

Jeanne Bouvier was later employed as a garment worker, or seamstress. Paid by the day rather than by the hour, there was no guarantee of work. Strict silence was enforced in these textile workshops, where she often stayed until 2am, sometimes with no dinner, only some bread and chocolate at 4pm. Her lodgings were a 45 minute walk away, and in the dead of winter or in the middle of the night she was often too tired or too cold to eat. It was no wonder she ended up in hospital with exhaustion. For some women, the only alternative was prostitution or suicide.

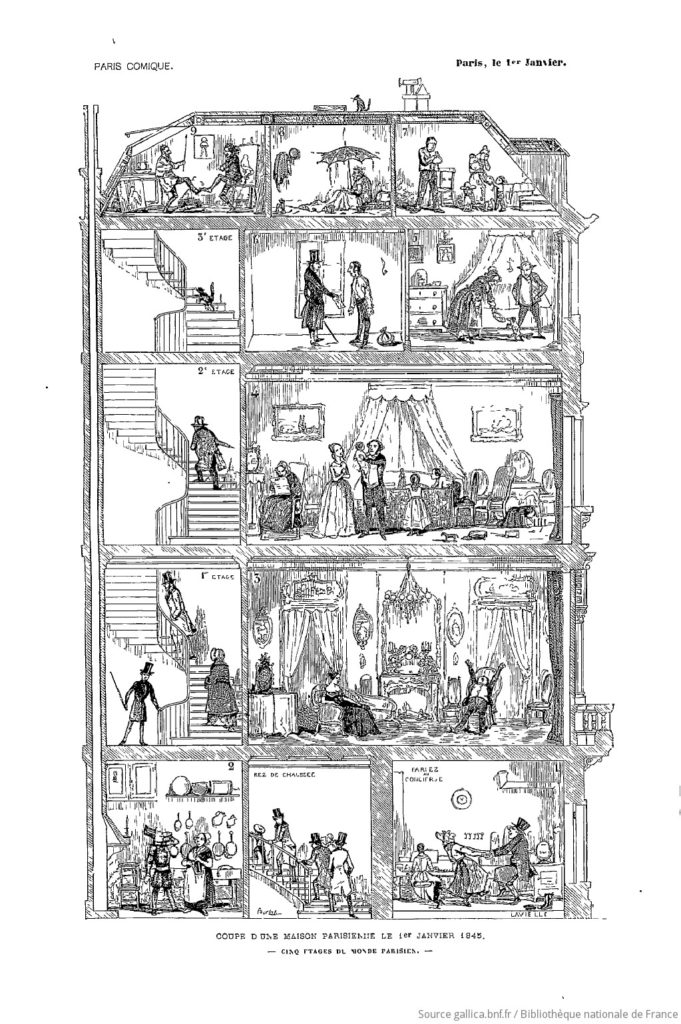

On the seventh floor of Jeanne Bouvier’s building was a young seamstress who worked for a large, luxurious Maison de haute couture on rue de la Paix, the heart of Paris fashion. Despite the high quality of her work she could barely afford bread and milk, and unable to pay her rent, she jumped out of her top floor window.

In 1892 a law was passed to restrict the working day for women to eleven hours, with a weekly day of rest. This was not legislation made to protect women, it was enacted out of fear of the falling birth rate. But in the world of ‘women’s work’, such as milliners and seamstresses who were more likely to be single, night employment continued.

A widowed shirtmaker from Rouen who made 127 shirts in a week, sleeping only 2 hours a night, earned only 10 francs total after costs (a kilo of bread would take 0.38 of her francs).

“This worker, who is 47, looks as if she is 60. Her food is made up of little more than little balls of minced pork, salted herrings and the cheapest of vegetables. She says that she gets no help from anyone and that life for her is an unalleviated burden.

Rapacious and greedy employers found ways to subvert the law on night work, such as forcing seamstresses to take work home to finish for no extra pay. Fines were small and hardly a deterrent, and it was easy to learn of impending visits of inspection. In 1906 a young garment worker suffocated to death in the wardrobe of a prominent couturier who forgot to let her out after an inspection visit.

It was well after the Belle Époque in Paris ended, with the advent of WWI, that women workers gained any rights, and finally at least a minimum wage.

As for the Opéra Garnier, it is still there, its dome rising splendidly amongst the rooftops, now one of Paris’ most iconic buildings.

Bibliography

Mary McAuliffe, Dawn of the Belle Epoque, Rowman and Littlefield, 2011

James McMillan, France and women 1789-1914 : gender, society and politics, Routledge, 2002

Karin Sagner-Düchting, Renoir: Paris and the Belle Époque, Prestel, 1996

No matter what period of history, for the wealthy, it is remembered as a great era: for the poor, however, it is Hell. Sadly, this has not changed.

So very true. History is always written by the victorious, and in this case, the women were anything but.