In the Louvre museum there is displayed a rather shocking painting of a naked Gabrielle d’Estrées with an equally naked yet unnamed sister tweaking her nipple. Supposedly announcing a pregnancy and upcoming royal marriage, it was deemed so disgraceful when it later hung in the Paris Prefecture, a green curtain hid the two women from public view. The escapades of the mistress-turned-almost queen Gabrielle d’Estrées are very well known, but who was the mysterious sister? There were in fact five to choose from. It is deemed likely that the nipple pincher was the youngest sister, Julienne Hippolyte Joséphine d’Estrées, married name Madame de Villars, whose outrageous antics scandalised high society in 17th century Paris.

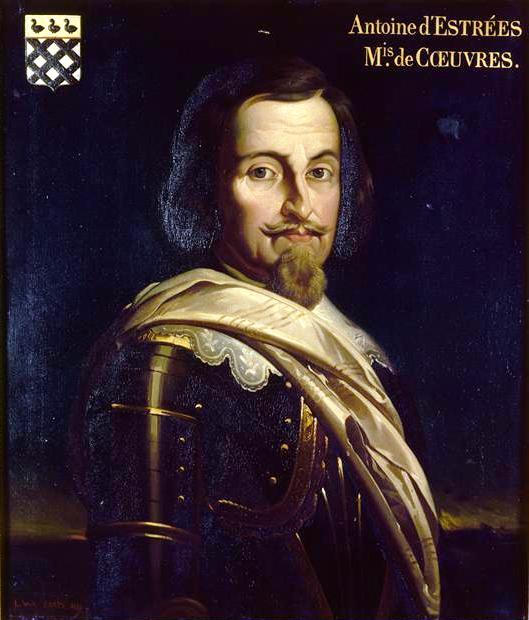

Julienne Hippolyte Joséphine d’Estrées (she used the name Hippolyte), born around 1580, was the youngest of eight children. Her mother, Françoise Babou de La Bourdaisière, was from an aristocratic family, though one supposedly full to the brim with vetches or ‘loose women’ according to gossip of the time. She was a mistress to Henri III, shamelessly took lovers throughout her married life and after deserting her children, shacked up with a marquis until they were both stabbed to death and mauled by a rampaging mob. Hippolyte’s father, Antoine d’Estrées, was a military man and a little more conventional, but his lineage was of the illegitimate kind, his grandfather being a royal bastard of the counts of Vendôme.

Her five sisters and one brother (the eldest died young) were called many things in their lifetimes, but were most often referred to in 17th century Paris as “the seven deadly sins”. Most of them married into high-ranking French families, thrice even for the only son, François-Annibal d’Estrées, of whom it was said was so dissolute and without scruples that he had slept with all six of his sisters.

Why was Hippolyte in the painting with her sister, the mistress to Henri IV? She probably had a brief fling with the king; she was young and beautiful and perfect for a monarch who could not keep his uncouth hands off women.

Mme de Villars was beautiful and gregarious, with small eyes and a large mouth, but her slim figure, luxurious hair and fine complexion were beyond compare.

Historiettes, Gédéon Tallemant des Réaux

However, it was Gabrielle who won the king’s heart, and was then free to arrange the life of her little sister.

Hippolyte married Georges de Brancas, Baron d’Oise and Duc de Villars, on the 6th of January, 1597. She was still a teenager at the age of 17, he was 32. Gabrielle, her sister, was at the height of her influence with the king, Henri IV, and a sumptuous wedding for the happy couple took place in Rouen, where the royal court happened to be at the time. It is likely the king was in attendance as he signed their marriage certificate. The wedding celebrations continued for two whole days; it was a magnificent feast by all accounts. However, malicious rumours soon spread that Hippolyte had scandalously lived with Georges for several months before they were married.

But scandal and shenanigans would follow Hippolyte through the rest of her life. Taking one or more lovers in 17th century Paris seemed to be the norm, one which Hippolyte embraced whole-heartedly, having many high-ranking amours during her married life. After the death of Gabrielle in 1599 she even tried to ensnare the king, but he was enamoured with his new favourite. This new royal mistress was Catherine Henriette de Balzac d’Entragues, of whom Hippolyte was insanely jealous, particularly as they were both also sleeping with the same young man (who was not the king). In 1608 Hippolyte maliciously tried to discredit Catherine Henriette by presenting Henry IV with letters in which his mistress disparaged him to her young lover, but was completely unsuccessful and found herself exiled from Paris to Normandy and her husband.

Related post: Normandy is the home of camembert. Which came first, the camembert or the brie?

The Duc de Villars was the governor of Le Havre after finishing his military career. He had inherited a large fortune, land and a title, but as neither he or Hippolyte had the slightest clue how to manage money, together they squandered much of their wealth.

A year after humbly returning to Le Havre, while listening to the sermon in church on a Sunday, Hippolyte found herself quite overcome. It was not a coup de foudre from a displeased God above, but of a much more amorous kind. Preaching the sermon was a Capuchin monk named Father Henri de La Grange-Palaiseau. According to Tallemant he was one of the most handsome men in France, a man of vast intelligence, a man from a well placed family but without means, which was probably why he chose the church as his profession.

From the first glimpse in the first sermon, Madame de Villars fell passionately in love with her priest. Suddenly filled with religious fervour she attended mass on a daily basis, leaving behind her usual extravagant gowns and wearing instead something simple but definitely more seductive.

She wore a sort of doublet (tight-fitting jacket) with high breeches and a scanty gauze skirt, which was almost transparent. Just think that with this doublet she had no coif (covering for the neck)… Adorned as such, and wearing her best plumed hat, each morning she stood facing the pulpit, without a mask, and with her throat very bare.

Historiettes, Gédéon Tallemant des Réaux

Yet none of this persuaded poor Father Henri. She went so far as to write to Rome to ask that her beloved priest hear her confession, claiming she had been so moved by his sermons she wanted to renounce her previously hedonistic lifestyle and devote herself to God. Easily obtaining Rome’s permission, she not-so-subtly arranged for her confession to be heard in the private chapel which just happened to be in her home.

But the duchess, instead of confessing her old sins, wanted to persuade the hapless monk to make new ones.

Historiettes, Gédéon Tallemant des Réaux

Father Henri eventually managed to escape her clutches and made his getaway into the forest. Learning of his desertion, Hippolyte mounted a horse and rode like a madwoman until she finally caught up with him. Pleading, crying, a little seducing, begging; nothing worked. By some sleight of hand, perhaps, the priest stole Hippolyte’s horse and fled to Paris.

Even then Hippolyte was still not disheartened. Pretending to vomit blood (it was not her own), and faking a dying illness, she was taken immediately to Paris for treatment. It took several letters and some time before she realised her priest could not be converted to sin even just a little, and from then she was miraculously healed.

Somewhat ironically, Hippolyte was a patron of the Capuchin convent in Honfleur, where Georges was later the governor. In 1828, a foundation stone at the convent was found, with the following inscription: “The year of salvation 1621 on the 10th day of June this stone was laid by the very powerful Lady Hipolite d’Estrées, wife of Monsieur de Villars, Marquis de Graville, governor of this town, Harfleur, Moteville, who had this chapel built in honour of the Virgin.”

According to Tallemant, Madame de Villars was the greatest charlatan in the world. With creditors knocking on her door daily in search of monies owed, she wrote to each and sought a meeting. At these individual meetings she told each creditor she had no money, but she could pay them in apples, thousands of pounds of apples they could then use to make enough cider to cover her debts. The happy cider-loving creditors, not realising she had told all of them the same lie, turned up to the apple farmer with hands outstretched only to find there were five hundred pounds of apples in total.

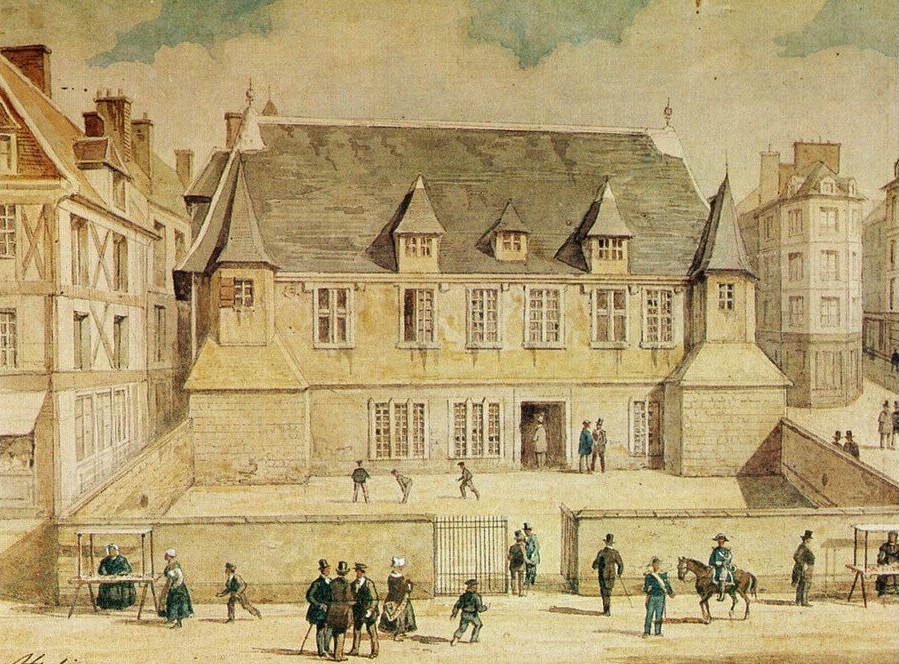

By the 1630s Hippolyte and Georges were living in Paris, though Tallemant notes they were less and less at the royal court at the Louvre, probably as they had little money. In fact, Hippolyte was so little remarked upon by the society of 17th century Paris that her date of death is unknown. Tallemant wrote in 1657 that she was still alive (and a beggar), but she is recorded as deceased at the marriage of her eldest son on 26 September 1649.

Georges died in 1657, living to the ripe old age of 92.

17th century Paris was a time of war, of modernisation, and even abandonment when Louis XIV upped and left for his new royal palace of Versailles. But the century was full of amazing women who began to find their voice amidst their legal and marital limitations. We only know of the outrageousness of Julienne-Hippolyte-Joséphine d’Estrées, we can laugh at her mad ride on horseback through the forest in desperate search for her priest, but as with all the women in French history, I just always wish we knew more.

What do you think of Madame de Villars? Tell me in the comments below!