Before the eighteenth century in France, there was little notion of privacy. Kings and queens got out of bed and dressed in front of a crowd of nobles, wealthy women held literary salons literally in their bedrooms, and the commoners lived with as many people as they could in small, dark rooms. But everyone needs a little space – even Louis XIV, who created the stifling and unbending rituals of the French royal court had to build several other châteaux just to escape the formality of his own creation (and to cavort with his mistresses). After the era of Louis XIV, aristocrats sought to escape in cosier rooms like music rooms, boudoirs and libraries. So when Madame Thierry designed her bedroom in the elegant Hôtel de la Marine, she had in mind a retreat, a beautifully decorated room for reading, taking tea with her intimate friends, and of course, sleeping.

Madame Thierry was born Cécile Marguerite Lemoine de Boullongne in Clermont, north of Paris, in 1734. She was a cousin of the famous artist Bon Boullongne, but her own family had a long history of serving the French royal family. Her father and both grandfathers were, respectively, valet, forestry official and architect du roi to Louis XV. There was no question she would enter the world of royal servitude, which she did in 1753 as a femme de chambre for Marie Leczinska, the Polish born queen of Louis XV. Her aunt, Marguerite Lemoine, was already in the service of the queen.

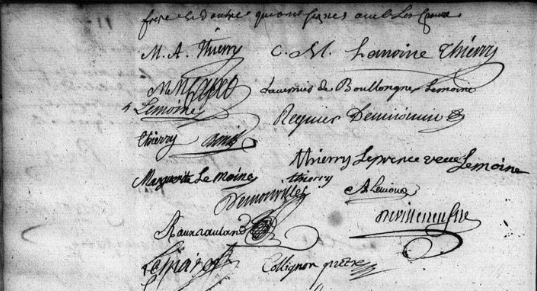

Her world was the opulence and extravagance of Versailles; she may not have owned it, but she lived it. She fell in love with a dashing young musketeer in the army, Marc-Antoine Thierry, and the two married in the church of Notre-Dame in Versailles on 13 February 1760. Thierry, enobled in 1769 and granted the barony of Ville-d’Avray in 1784, was a rising star in the French court whose father had been of tremendous support to a young Louis XVI when he lost both his parents as the dauphin. When he became king, Louis XVI appointed Thierry to the prestigious and coveted position of first valet which gave him almost unlimited access to the king.

At the same time the now Madame Thierry was occupied with the dauphine and later queen, Marie Antoinette. The adolescent and naïve and archduchess arrived in France in 1770 already married by proxy to Louis, and it supposedly took seven years for the marriage to be consummated. Madame Thierry served as her première femme de chambre from Marie Antoinette’s arrival until 1776, so she was privvy to the most intimate details of the royal life. Whilst she claimed to have left the post due to ill health, the rumour circling the gilded halls of Versailles was that she had been telling all and sundry that stains left on the young queen’s sheets were proof that she and Louis had in fact already consummated their marriage. While the sexual machinations of a royal marriage were generally an accepted topic of discussion, such indiscreet behaviour from a close confidante was cause for dismissal.

In 1784, Thierry was assigned the important position of Intendant of the Garde-meuble de la Couronne, the department responsible for the purchase and oversight of furniture and decoration for the royal residences (of which there were many). He, his wife Cécile and their four children moved into the Hôtel de la Marine on the place Louis XV (now place de la Concorde). This magnificent mansion, with neoclassical facades had been especially constructed to house the collections, workshops and private apartments of the Garde-meuble de la Couronne.

Madame Thierry chose for her private bedroom the billiard room of the former Intendant, keeping some of the decoration but giving it her own personality. The room opened directly onto the black and white tiled Italian style terrace and offered a wonderful view of the equestrian statue of Louis XV and further along to the Seine river. In less than ten years one could also stand on the terrace for an unhindered view of the execution of Louis XVI and then Marie Antoinette.

The opulent bed was called lit à la Polonaise (Polish bed), named after the Polish queen, and was very popular in the second half of the eighteenth century. Its sumptuous oval canopy furnished in luxury fabrics supported four curtains tied back onto metal columns attached to the corners of the bed, allowing privacy if needed. The head and foot of the bed were gilded and covered in damask, with roses and myrtles as a symbol of Venus. Her husband’s bed, now on display at the Museum of Fine Art Boston, was designed by French furniture makerJean-Baptiste-Claude Séne, so it is possible Madame Thierry’s bed was also created by this famous menusier. On the walls is an exquisite dark green brocatelle. Brocatelle was a rich and heavy silk created to look like the design was embossed on the fabric, and was used extensively in eighteenth century decoration. Of course this is not the original fabric, but was woven using techniques of the time and is as close to the actual material as possible. The gold painted cornices and wood panels have also been restored to their original state.

Historical inventories, letters and court records have given us much detail as to how Madame Thierry’s bedroom would have looked. In 1787, Thierry ordered two superb mahogony chests of drawers for this bedroom, with simple lines, gilded trim and an antique patina, as was the latest in furniture. One of these original commodes can be seen at the Louvre museum, as shown in the image above.

Furniture of the late eighteenth century was simpler; the neoclassical Louis XVI style generally meant straight, fluted lines and geometric forms, which we can see in the chairs in Madame Thierry’s bedroom. Chairs, always covered in luxury fabrics and usually part of at least one matching set, were an essential part of a room, and were often numerous. And in this room, where Madame and Monsieur Thierry aspired to the highest echelons of society, even the tiny, plush dog kennel conformed to the latest style.

Thierry was a man who loved fine things, and he was not above using his royal position to obtain them. In 1787 Thierry ordered a clock from François Caranda, master horloger, at the expense of the king. However, the clock was not for the king; it was for Madame Thierry’s bedroom. Described as a mantle clock in gilt bronze with a black marble base, decorated with two doves and musical instruments, it was an expensive and opulent additon to a bedroom.

But it was a bedroom all the same, and the objects on display give a glimpse into the world of Madame Thierry. On the bedside table, if you look closely, you can see the treasured fan which was a gift from the queen Marie Antoinette. Perhaps she soothed a crying grandchild in the chair next to the bed, took tea next to the fireplace protected by its silk firescreen, or played a game and gossiped with a close friend whilst sitting at the small table on green damask chairs. Letters were written in the small library which adjoined her room, overlooking the colonnaded terrace, with her armchairs painted white and upholstered in toile de Jouey. It seems like a happy place.

Within a few years, the world she knew had ended. The first weapons fired at the Bastille, the start of the French Revolution, had actually been taken from the arms collection at the Hôtel de la Marine, and within a short time the building itself was seized and handed over to the revolutionaries. Thierry was accused of stealing gold and diamonds from the royal treasure held at the Hôtel, was imprisoned and then unfortunately killed during the September massacres in 1792. Thankfully Madame Thierry and her children survived the Reign of Terror in which tens of thousands died in Paris, but what she did after this is not known.

She died on 4 May 1813 and is buried at the Père Lachaise cemetery in Paris. Her gravestone reads:

Here lies the mortal remains of Dame Cecile Marguerite Lemoine, première femme de chambre to Queen Marie-Antoinette of Austria, widow of M. Marc-Antoine Thierry de Ville d’Avray, first valet de chambre to Louis XVI, one of the Commissioners General of his household, and marshal-de-camp, born on December 6, 1734 and died on May 4, 1813.

Who will find a strong woman? She is no less precious than the things which are most rare; she receives blessings from the children she has raised and gratitude from her husband. Grace is an illusion, beauty is vanity; but the woman who trusts the Lord will be honoured, she will receive the fruit of her actions, and her works will praise her.

Madame Thierry’s bedroom, as well as the rest of her beautiful apartment can be visited at the Hôtel de la Marine, Place de la Concorde, Paris.

All photos, unless otherwise stated, are the property of the author and are therefore protected under copyright.

Thank you – for your wonderful history “ lessons “ .

You’re very welcome! I’m so pleased you enjoyed the article.